Welcome to the third part of this five-part series, in which I apply the f1metrics model of driver and team performance to simulating historical hypothetical situations.

If you want to check out the previous articles in this series, they are linked here:

Part II (Kubica, Clark, Donohue, Revson)

Method

For each hypothetical scenario below, I simulated either the extension/comeback of a driver’s career or a change in teams during their career. Two types of outcomes are presented for the simulated scenarios:

(i) The adjusted driver performance rankings (in ppr) for each season, including the driver’s predicted hypothetical performance at that age and with that level of experience. This is a ranking (ranging 0-10) of absolute driver performances, taking teams out of the equation. In other words, it’s how the model predicts the drivers of that season would have performed in equal machinery. This is the same approach I use for my end of season driver rankings each year.

(ii) The predicted World Drivers’ Championship standings for each season. In cases where these tables are presented, I am including the effects of a driver’s hypothetical team on their points scored. In this simulation, I have used the team’s average reliability that season to generate the number of mechanical DNFs. To generate point tallies, I mapped the model’s scoring rate function to all other points scoring systems in F1 history so that I could convert between ppr and points scored.

Stefan Bellof: Germany’s lost champion?

In the years following his untimely death in 1985, Stefan Bellof became a cult hero among F1 fans. At the time of his death, Bellof was nearing the end of his second F1 season and had made just 20 race starts. In evaluating cases such as Bellof’s, it’s difficult to be objective. His career lives on in memory due to the moments of great brilliance and bravado, which tend to obscure anything else. There are still many fans who regard Bellof as almost a guaranteed world champion, had he lived beyond 1985. (Instead, Germany had to wait for Michael Schumacher to win the title in 1994.) I was therefore fascinated to see what the completely impassive f1metrics model would make of his case.

There are many legendary stories relating to Bellof’s career. One of the best known is his performance at Monaco 1984. The Tyrrell team was running two rookie drivers in 1984: Stefan Bellof and Martin Brundle. In qualifying for Monaco, the car was not competitive. These were the days of prequalifying, meaning slower cars did not necessarily qualify for the race. In Monaco, although 27 cars attempted qualifying, only 20 cars were allowed to make the start. Brundle was 3.71 seconds off pole and 22nd fastest, narrowly missing out on starting the race. Bellof was 3.46 seconds off pole, meaning he just scraped through to qualify 20th. This seemingly minor detail from qualifying would have profound ramifications for the race.

The 1984 Monaco Grand Prix was hit by a torrential deluge. By lap 24, 11 of the 20 starters had retired. Seven of them had crashed in the near-impossible conditions Four others had succumbed to water-related retirements, chiefly electrical faults.

At this stage, the rain started to get even worse. Alain Prost, who was balancing extreme caution with speed, was leading the race by almost 30 seconds. The lap-times were so slow that Prost was having difficulty maintaining operational temperatures in his brakes.

Between lap 24 and the controversial red-flagging of the race on lap 32, the race gained enduring status as two rookie drivers took charge. While Prost attempted to maintain his lead in the treacherous conditions, both Ayrton Senna and Stefan Bellof began closing on him extremely rapidly. I have illustrated this in the graph below, based on compiled lap charts.

Gaps from Bellof to Prost and from Senna to Prost across the 1984 Monaco Grand Prix.

Senna and Bellof were clearly taking huge chunks out of Prost’s lead towards the end, with Senna gaining an average of 3.7 seconds per lap on Prost over the last 5 laps and Bellof gaining an average of 4.3 seconds per lap on Prost over the last 5 laps. At that rate, Senna would have caught Prost by lap 34 and Bellof would have caught Prost by lap 36. It’s often claimed that Bellof was also catching Senna at a meteoric rate in the closing laps, but this clearly isn’t true. They were keeping similar pace and it would have taken over 20 laps for the gap between them to close, after which passing would have been another question. Though it must be noted that Senna’s own situation was precarious, as he had sustained suspension damage running over the kerbs at the chicane, and his car might not have lasted much longer had the race continued. Indeed, any of the drivers could have ended in the barrier on any given lap had the race continued.

Bellof’s performance is considered particularly remarkable, given we now recognize that Senna was one of the greatest wet-weather drivers in history. Across his career, Senna was 2.5 times more likely to win a wet race than a dry race, and he was no slouch in the dry.

There’s one other really important bit of context here. In 1984, every team except Tyrrell had switched to turbo engines. From 1966-1985 (and 1950-1960), both naturally-aspirated and turbo engines were permitted, with different sizes for competitive balance. The allowance of turbo engines was virtually irrelevant until the late 1970s when turbo engine technology advanced. For several seasons into the 1980s, turbo and naturally-aspirated engines competed for supremacy, with turbos having greater power but also being much thirstier, heavier, more unreliable, and more difficult to drive (due to turbo lag).

In 1984, Tyrrell sought to use their key differentiator (the naturally-aspirated motor) to achieve a competitive advantage. With a simpler engine and lower fuel demands, they could build a much lighter car than others. However, minimum weight regulations required that they add ballast. While the ability to place ballast gave them better weight distribution, they sought a bigger advantage still. They constructed a car that was substantially underweight — by reportedly up to 70kg under racing conditions. Using water-cooled brakes, they would fill the water tanks with a mixture of water and lead shot late in the race, meaning the car would just make the official weight at scrutineering.

The loose lead shot was clearly contravening the regulations, but the team decided to take a chance. In the context of Monaco 1984, Bellof may therefore have been at a significant mechanical advantage on a wet street circuit, due to the lighter, more nimble car and, crucially, no turbo lag.

When Tyrrell were ultimately caught later in the year, they were given one of the most draconian penalties in F1 history: all of their 1984 results were struck from the record. On the books, Bellof therefore didn’t have any classified result in that famous 1984 Monaco Grand Prix, nor any other race in 1984. This is problematic for ranking Bellof. Not only are some of his best performances struck from the record, he has only 7 counting races (excluding mechanical DNFs) in 1985. Not enough for any sort of reliable ranking.

Bellof and Brundle, Tyrrell teammates in 1984 and 1985

If we are going to rank Bellof, we really need to resurrect the 1984 results. I therefore did that, reinserting the results of Tyrrell drivers into the 1984 season, adjusting other cars’ finishing positions accordingly. With these data, we can begin to make a serious examination of Bellof’s racing credentials. During his time in F1 in 1984 and 1985, he raced alongside Martin Brundle and Stefan Johansson.

The first thing we should examine is Bellof’s record relative to his teammates. He faced Johansson at only two races, with a qualifying record of 1-1 (both times qualifying within 2 tenths of each other) and a race record of 1-1.

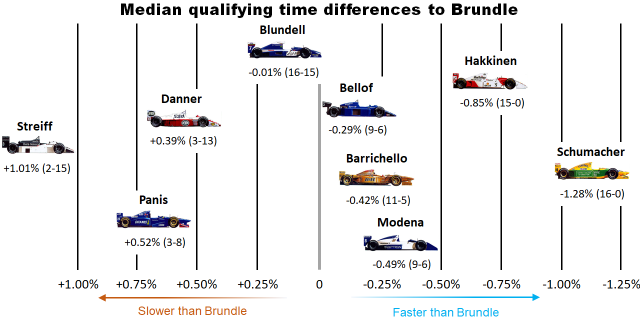

The record against Brundle is more informative, since they were the main Tyrrell drivers across 1984-1985. In qualifying, Bellof seemingly had an edge, beating Brundle 9-6 with a median time difference of 0.29%. Notably, Brundle was never a particularly good qualifier, so a slightly positive record there is not an indication of exceptional pace. Brundle’s head-to-head qualifying record against various teammates is illustrated below. By this measure, Bellof ranks similar to Barrichello or Modena. Schumacher, who leads the group, was actually in only his first full season of F1 when he faced a more experienced Brundle.

Due to poor reliability, there are actually only three races where neither Bellof nor Brundle had a mechanical DNF. In these three races, Bellof came out ahead 2-1. Their points scoring rates (on which the f1metrics model is based) were similar. Bellof scored 11 points (6th, 5th, and 3rd in 1984; 6th and 4th in 1985), while Brundle scored 8 points (5th and 2nd in 1984). I note that in a few races, Brundle and Bellof used different engines, racing Tyrrell-Ford vs. Tyrrell-Renault, so they are not treated as teammates for these races.

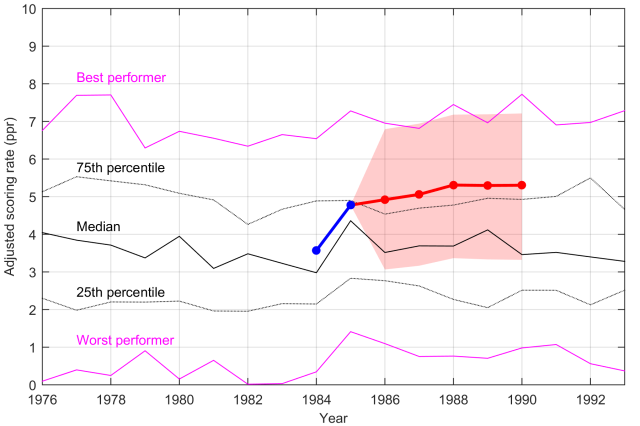

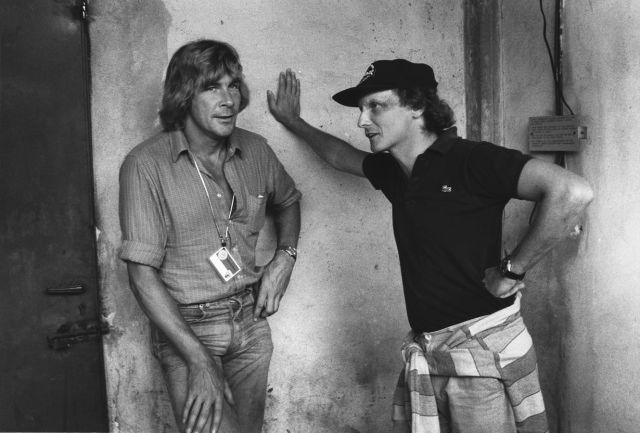

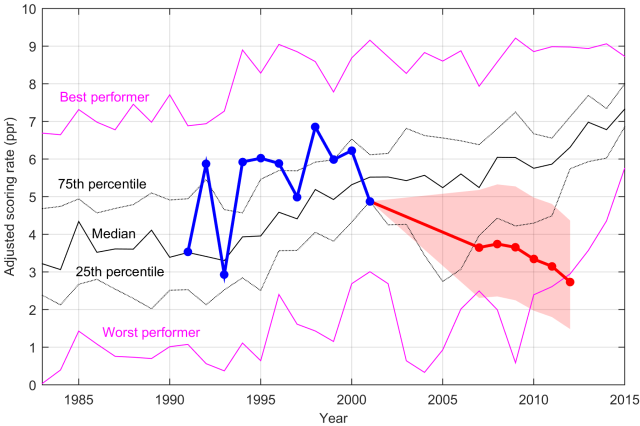

Applying the f1metrics model to the data, including the reinstated 1984 results, allows us to project Bellof’s future performances, had he raced beyond 1985. This generates the trajectory shown below.

Bellof was 27, in his second F1 season, when he was killed in 1985. Based on this, The model predicts that he had some scope to improve with age and further experience, but most of his predicted improvement on this front would have been expected to occur across 1984 to 1985.

The range of uncertainty on Bellof’s future performances is large, due to the small amount of data from his career. He would most likely have been among the stronger drivers on the grid and almost certainly among the top half of performers on the grid in the late 1980s. Though he might have improved to become one of the absolute best drivers, the model predicts this as an unlikely scenario.

Supposing Bellof had survived, he would likely have become a Ferrari driver. Bellof had apparently agreed terms and was read to sign a contract to race at Ferrari for 1986 and 1987. For the sake of the hypothetical, we will imagine he would have replaced Michele Alboreto there.

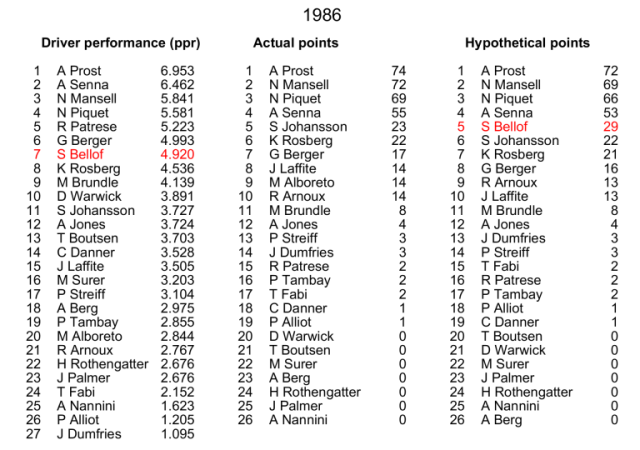

In 1986, the model predicts that Bellof would have been about the 7th best performing driver on the grid and, in Alboreto’s place, would have been Ferrari’s lead points scorer with 29 points to Johansson’s 22 points. Not enough to challenge for the championship, but likely enough to feature several times on the podium.

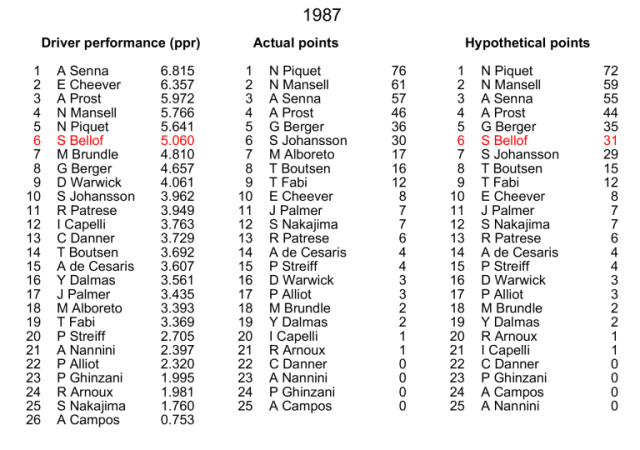

Had he continued to race at Ferrari in 1987, the model predicts that Bellof would have slightly outperformed teammate Berger. But, due to Berger’s run of fewer mechanical DNFs in what was an extremely unreliable car, he may have come out slightly ahead of Bellof in the points standings. Neither driver could realistically have competed with the dominant Williams team for the title.

Had he continued to race at Ferrari in 1987, the model predicts that Bellof would have slightly outperformed teammate Berger. But, due to Berger’s run of fewer mechanical DNFs in what was an extremely unreliable car, he may have come out slightly ahead of Bellof in the points standings. Neither driver could realistically have competed with the dominant Williams team for the title.

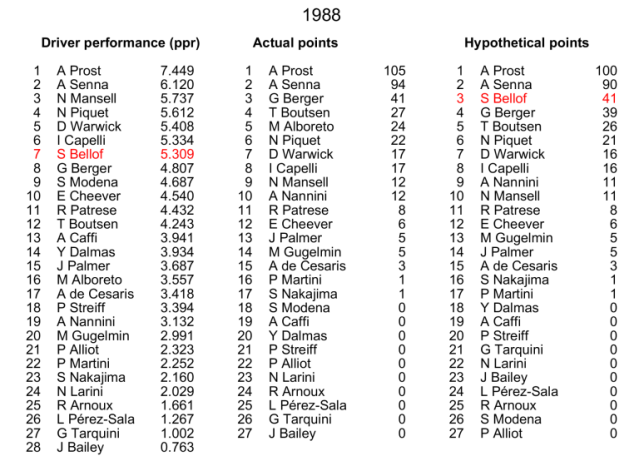

In 1988, Ferrari faced the unbeatable McLaren-Honda team. The model sees Bellof as scoring best of the rest, slightly ahead of teammate Berger.

In 1988, Ferrari faced the unbeatable McLaren-Honda team. The model sees Bellof as scoring best of the rest, slightly ahead of teammate Berger.

McLaren continued their extremely strong form into 1989 while Ferrari faltered. Neither Bellof nor Berger could have challenged for regular wins, but again the model sees Bellof as potential team leader ahead of Berger.

McLaren continued their extremely strong form into 1989 while Ferrari faltered. Neither Bellof nor Berger could have challenged for regular wins, but again the model sees Bellof as potential team leader ahead of Berger.

By 1990, Ferrari were a force to be reckoned with, taking the title down to the wire with McLaren. In this hypothetical scenario, Bellof partners reigning champion, Alain Prost, taking the seat that Nigel Mansell actually held. By the model’s prediction, Bellof would have finished around 3rd in the championship, given a typical run of reliability that year (Mansell had an abnormally poor run with 8 of the team’s 11 mechanical DNFs).

By 1990, Ferrari were a force to be reckoned with, taking the title down to the wire with McLaren. In this hypothetical scenario, Bellof partners reigning champion, Alain Prost, taking the seat that Nigel Mansell actually held. By the model’s prediction, Bellof would have finished around 3rd in the championship, given a typical run of reliability that year (Mansell had an abnormally poor run with 8 of the team’s 11 mechanical DNFs).

In summary, the model sees Bellof as a likely race-winner, but probably not ever challenging for F1 titles, unless he happened to land in a dominant car (e.g., Williams in 1992). A great lost talent, no doubt, but perhaps not a lost champion.

Ex-champion comebacks

Ex-champion comebacks

Several former champion drivers have been lured into Formula 1 comebacks, usually with underwhelming results. Alan Jones achieved next to nothing with his two comebacks. Niki Lauda clinched a dramatic third world championship on comeback, but otherwise didn’t seem to have his 1970s pace — in qualifying particularly he was a completely different driver. Michael Schumacher’s comeback from 2010-2012 proved there’s really no beating age-related decline. Kimi Raikkonen had a successful 2012-2013 comeback with Lotus, but the years of poor performances at Ferrari since have done major damage to his legacy as a driver.

Alan Jones on his second Formula 1 comeback in 1986, racing for Team Haas.

There are other cases of champion drivers toying with the idea of a return, but ultimately (wisely) reconsidering. Using the model, we can investigate how those comebacks would likely have panned out.

James Hunt ended his Formula 1 career early in 1979, aged 31, having completed only six and a half seasons. Comebacks were seriously evaluated in 1980 for McLaren and 1982 for Brabham. The latter comeback would have put him in competition for the World Drivers’ Championship against teammate Piquet in 1983, and the model thinks he could have been seriously competitive (Piquet’s ppr in 1983 is 5.904, Hunt’s projected ppr in 1983 is 5.824).

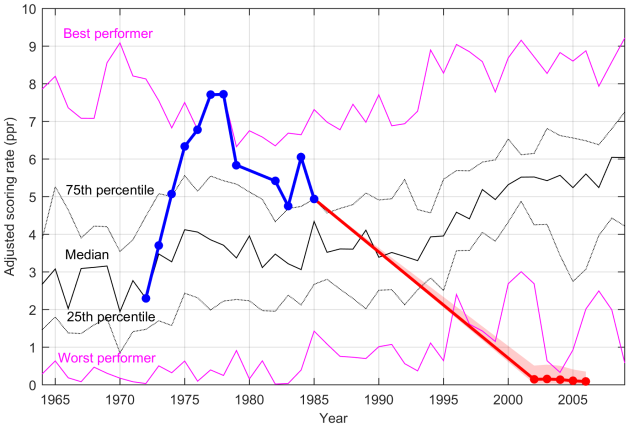

As the graph below shows (green curve), Hunt on a 1980s comeback could probably have remained competitive with the top few drivers (including Niki Lauda, opening the possibility of a second Hunt-Lauda championship battle!) until about 1985, aged 38. The idea isn’t ridiculous. Jackie Stewart was apparently faster than the Benetton team’s regular drivers Thierry Boutsen and Alessandro Nannini when he tested their car at the Dearborn Proving Grounds in the late 1980s.

Estimated performances for James Hunt, assuming a comeback in 1982 (green) or 1990 (red). The colored dots and curves show the most probable prediction. The shaded regions indicate the combined standard error in estimates of Hunt’s driving performance, as well as age and experience effects on performance.

In 1990, Hunt again considered staging a Formula 1 comeback, this time motivated by deep financial troubles. He was now aged 42 and was 11 years post-retirement. In testing, Hunt was apparently well off the pace and the idea was pursued no further. By the model’s estimation, Hunt would have been among the weakest drivers on the grid had he actually returned. Moreover, it’s reasonable to assume that Hunt may have experienced greater age-related performance decline than a typical driver due to his hard-living lifestyle. This would push him towards the lower end of the red shaded region.

James Hunt driving for Williams in preseason testing in 1990 at Paul Ricard.

Another former champion who perhaps retired prematurely was Mika Hakkinen, who left the sport at the end of the 2001 season, aged 33. At that time, he seemed burned out and lacking motivation after weathering multiple consecutive championship campaigns, but Ron Dennis extended an offer for Hakkinen to return to the cockpit any time. In 2006, with McLaren needing a replacement for the outgoing Kimi Raikkonen, Hakkinen seriously considered a return to Formula 1. He spent time training with the team and ran a test. On the test day, he was the slowest runner, with his best time over 2 seconds slower than GP2 driver Lewis Hamilton. Hakkinen’s plans to return to Formula 1 were canned, but in his defense Hakkinen says the car was not running at its best that day.

Mika Hakkinen testing for McLaren in 2006.

How does the model see a 2007 comeback going for Hakkinen? During his main career, Hakkinen is ranked by the model among the top few drivers in most years, albeit well below Schumacher’s level. In 2007, he turned 39. Between his advanced age and his lack of recent experience, the model sees him as likely one of the weaker drivers on the grid. In other words, Hakkinen chose wisely in hanging up the F1 helmet rather than attempting to return amidst a new competitive order.

Finally, for a bit of fun, and as a tribute to Niki, let’s revisit the time that Lauda drove a Formula 1 car aged 52. In early 2002, as the team principal of Jaguar, he decided to run some laps in testing to try to better understand his drivers’ feedback on the car. Pushing hard, he spun the car several times. Ultimately, his best time was over 10 seconds off the pace. With more running, he surely could have gotten closer than that, but it was nonetheless indicative of how difficult it is to reenter the competitive fray.

Niki Lauda testing for Jaguar in 2002

Below, we can see the model’s prediction of what would likely have happened if Lauda had genuinely attempted a full-time Formula 1 comeback in 2002. While he was undeniably an all-time great in his prime, he would have been comfortably the slowest driver on the grid in the early 2000s.

But you can bet he would have been brutally honest about whatever his pace was…

Fascinating, thank you.

I’m a sucker for those little car profile images ever since playing grand prix manager 800 years ago. Btw the predicted results tables always look a bit blurry on my screen and I can’t load the image of Lauda in a Jaguar test.

Andrew,

Thank you for the post!

Great use of the model. I follow your blog for the analitics done on Formula 1 data, I love both analitics and F1. But this one, the narrative and all the additional info on the Tyrrell story in the 84 season, the test done by Lauda on Jaguar in 02… Simply great reading for anyone who happens to like the sport.

Nice but you should also do an analysis on what would happen if those drivers never left to begin with. Schumacher for example should easily be able to take championships in 2007 and 2008

Yes, I think that’s pretty obvious, there’s no comparison, and the model agrees, between raikkonen, massa and schumacher: if raikkonen was able to barely win the title and then massa to barely lose it with very competitive ferraris, a 38 and 39 years old schumacher should do it just fine!

Amazing and fascinating! I did not know all the gems about Stewart and Hunt testing etc. Every article here is a reading savoury :). Thank you!

Great stuff!

Great post, love this hypotectical series, I’m hoping Ascari comes up since even in the model he was close to Fangio which is an amazing achievement, admittedly Ascari was in Lancia I think when he died but if he went back to Ferrari in 1956 it would have made up an amazing season battle between the two as teammates. If possible could you post the hypotectical results for Hunt if he did comeback in 1982 for Brabhem? His predicted performance puts him around the top 5 drivers at the time and in a slightly optimistic scenario he’s the best on the grid, as you mentioned he could have fought for the title in 1983 so it would be really interesting. On a different note, will there be a junior report at the end of the year? I had a look back and one of the drivers you noticed in 2017 (Oliver Askew who won the US FF2000 that year) now has also came third in the Mazda Pro Championship and all but won the IndyLights championship this year, giving him an achievement score of 106 and an excitement score of 35.33.

Great work as always!

He’s obviously not a world champion, but an analysis of Luca Badoer’s comeback comes to my mind… I guess it would be useful to test your model for age/experience combined effects.

There’s one more hypothetical comeback I’m interested in: Michael Schumacher. It seems he was on the verge of returning to Ferrari when Massa was injured but an injury of his own ended the pursuit. How competitive could he have been? Or what if he had not retired in 2006 – what would he have achieved in Ferrari and later in Mercedes?

[…] the model allows predictions of how drivers would have performed at different ages, such as in my historical hypotheticals series. For example, below is a prediction of how James Hunt would most likely have performed had […]

[…] Part III (Bellof and ex-champion comebacks) […]

[…] Part III (Bellof and ex-champion comebacks) […]

[…] determination of Brundle’s level relative to others. In the plot below, reproduced from my historical hypothetical series, we can see how Brundle’s qualifying performances rated relative to each of his […]