Welcome to the second part of this five-part series, in which I apply the f1metrics model of driver and team performance to simulating historical hypothetical situations. Consider this a quantitative approach to tackling some popular but difficult to resolve talking points in Formula 1 history. The point of this series is not to be taken too seriously, so please try to enjoy it in that spirit!

To review the previous article, see here:

Method

For each hypothetical below, I simulated either the extension of a driver’s career or a change in teams during their career. Two types of outcomes are presented:

(i) The Driver Performance (in ppr) for each season. This is a ranking of absolute driver performance, taking teams out of the equation. In other words, this is how the model predicts the drivers would have relatively performed in equal machinery. This is the same approach I use for my end of season driver rankings each year. It takes a driver’s age and recent experience into account.

(ii) The predicted World Drivers’ Championship standings for each season. In cases where these tables are presented, I am including the effects of a driver’s hypothetical team on their points scored. To generate these, I mapped the model’s scoring rate function to all other historical points scoring systems.

How long could Jim Clark have dominated?

Jim Clark on the way to his final victory.

Jim Clark stood head and shoulders above his peers in the mid-1960s and remained the sport’s top driver, aged 32, at the time of his death in 1968. Notably, in my all-time driver ranking list from a few years ago, he claimed the all-time #1 spot, ahead of all-time greats such as Schumacher, Fangio, and Stewart. In short, Clark was something really special.

It’s natural to wonder how much longer Clark could have dominated the sport, especially since drivers tend to stay near their peak at least into their mid-thirties. Had he survived into the 1970s, could he have beaten Rindt, Stewart, and Fittipaldi? Could he have even still been competitive into Lauda and Hunt’s era? It’s crazy to consider, but based on his age and talent, entirely plausible.

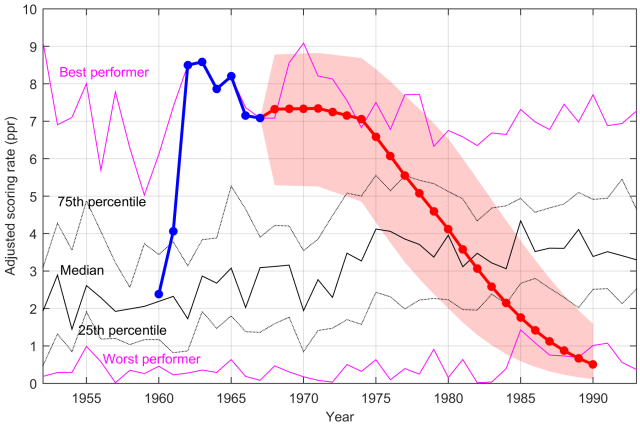

The graph below shows Clark’s predicted performances all the way up to 1990 (age 54), relative to other drivers’ performances across that time period.

These predictions indicate that Clark could have realistically been a top driver (perhaps even the best driver on the grid in some seasons) up to about 1974. Imagining Clark dicing for position with the likes of Reutemann and Fittipaldi is jarring, since they tend to be mentally compartmentalized into different eras, but that’s what could have unfolded. Based on his projected performance levels, Clark would have likely remained capable of taking race wins and even potentially titles in a strong car up to about 1977 (aged 41). By 1980 (aged 44, the same age at which Brabham retired from Formula 1), he would have been well past his best, and if we imagine he decided to just continue on racing for the hell of it, he likely would have become the worst driver on the F1 grid as late as 1990 (aged 54). An absurd, but illuminating, result.

This forecast assumes Clark would have smoothly adapted to the advent of wings, which were just beginning to sprout in his final season, followed by the relentless piling on of downforce throughout the 1970s. But given how other drivers adapted to this change, there’s little reason to think Clark could not have done the same. After all, he was one of the most versatile drivers in history, excelling in all manner of single seaters, sports cars, and touring cars. Let us not forget that Clark was involved in the nascent development of wings for Formula 1 before they appeared in races. Inspired by his own experience with a Vollstedt IndyCar that featured small wings, he encouraged Lotus to begin experimenting with their own.

As far as team selection goes, it’s difficult to know what course Clark’s career could have taken. He had reached revered driver status by 1968, meaning were he to approach any team for a seat, they would gladly have taken him. Lotus, however, remained the great innovators and generally the team to beat at that time. Ferrari were nowhere in F1 in 1968-1969 due to devoting resources to the World Sportscar Championship, so a move there probably would not have been seriously considered earlier than 1970.

Let’s suppose in this hypothetical that Clark remained loyal to Chapman and Lotus. The first order of business would be Clark winning the 1968 season, which he had started with a race win before his untimely death. By the model’s estimate, Clark would have stormed to this title by 15 points (back when a victory was 9 points) ahead of teammate Hill. In this timeline, Hill would therefore win only one championship.

Following Clark’s death, Chapman appointed Jochen Rindt for the 1969 season. At that time, Rindt was an extremely promising young driver. He had won 5 of the 10 races in Formula 2 in both the 1967 and 1968 seasons. He had also outclassed Jack Brabham in the highly unreliable 1968 Brabham-Repco, taking two poles and two podiums, while Brabham could qualify no higher than 4th.

In the event that Clark survived and won the 1968 championship, Chapman would have needed to choose between the safe option of retaining Hill (now 39) or picking up Rindt. I will assume Chapman chose the ambitious option and fielded Clark and Rindt as his two drivers, putting Hill into an earlier retirement.

Jim Clark with Jochen Rindt, his hypothetical teammate for 1969-1970.

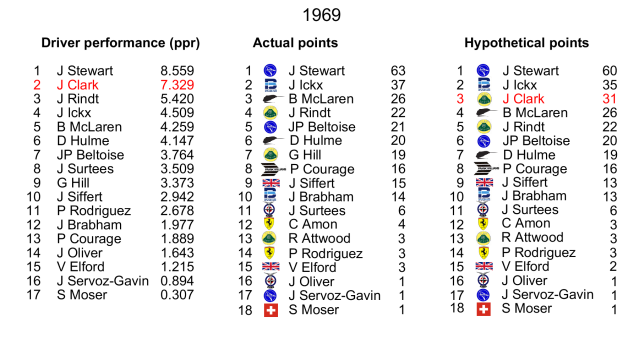

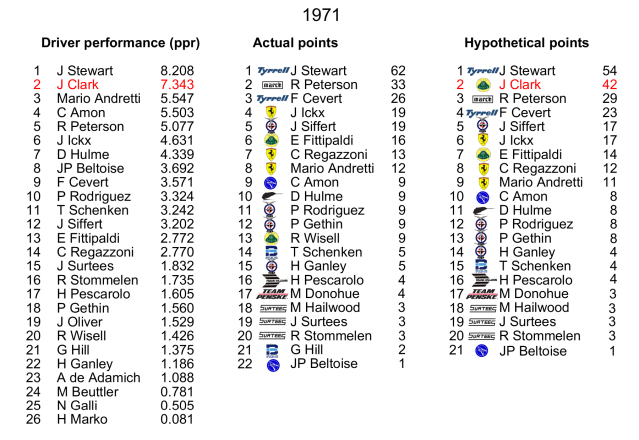

With Rindt still finding his feet, the model sees Clark as the top performing Lotus driver in 1969. But neither driver would have been any match for Stewart in his dominant Matra MS80. This was a difficult season for Lotus. Chapman had planned to transition from the Lotus 49 to the new four-wheel drive Lotus 63, but the latter proved less competitive than the former.

In 1970, Lotus had a very competitive package again. Stewart was performing near the top of his game, but the new March 701 was a difficult car to drive and fell behind in development as the season wore on, effectively extinguishing his hopes of defending the championship. To compound matters, the new Tyrrell 001 chassis, to which Stewart switched in the final three rounds, was incredibly unreliable.

Instead, there was a renewed threat from Ferrari, who switched focus back from sportscars to F1 and had arguably the season’s best car. Meanwhile, Rindt delivered what is rated by the model as one of the all-time best season performances, winning all 5 of the races in which he did not have a mechanical DNF. By the model’s estimation, this would have been enough to outperform Clark in a typical season for the Scot. The outcome of the championship would therefore rest on Monza 1970, where Rindt was tragically killed by a brake failure and thus did not participate in the last four races. In the hypothetical, Clark wins the championship by virtue of these events. If Rindt had instead survived in this timeline and participated in the last four races, he would be the predicted champion.

For 1971, having lost his two star drivers (Rindt and Clark), Chapman promoted the inexperienced but very talented Fittipaldi to team leader, with Wisell as a clear number two driver. With a strong car, and without any similarly brilliant drivers near the top of their game, Stewart took an easy title.

In this hypothetical timeline, we can imagine Clark paired with Fittipaldi instead. By the model’s estimation, the performance of the Lotus 72C/D was actually well poised with the performance of the Tyrrell 001. We could have thus seen something close to a fair fight between Clark and Stewart.

Jackie Stewart with Jim Clark: master and protege, but they could have become intense rivals in this timeline.

The model predicts a narrow victory to Stewart, in what would likely have been a championship featuring some classic head-to-head duels between the two close friends and two of the sport’s all-time greats.

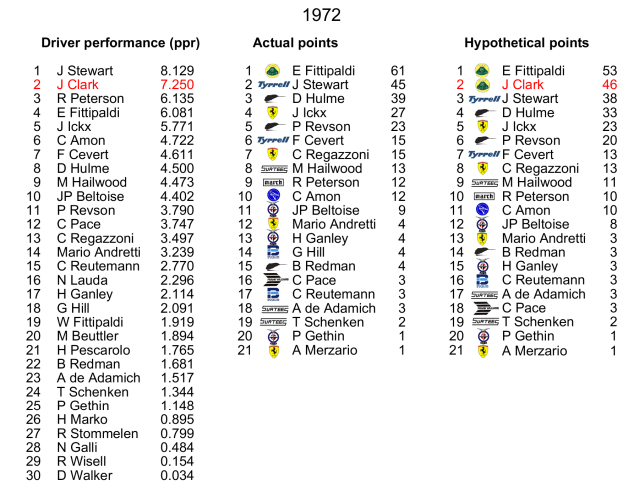

By 1972, Fittipaldi was performing at his best, and the Lotus 72D was more than a match for Stewart’s Tyrrell. By the model’s estimation, Clark would still have been a stronger performer than Fittipaldi, yet in the simulation Fittipaldi comes out narrowly ahead on points to win the title. Why is this? The answer is simply car reliability. Fittipaldi had 3 mechanical DNFs in 12 starts, whereas his teammates had 6 mechanical DNFs in 12 starts. Since the model simulation considers the team’s overall reliability, Clark would lose the championship given an average run of reliability, due to Fittipaldi’s relatively fortunate run (cf. Hamilton losing the title to Rosberg in 2016). Of course, we could get into the question of whether Fittipaldi’s weaker teammates were getting the same mechanical service as he was, but that’s further than I want to go with this.

The 1973 season was Jackie Stewart’s swansong, to the surprise of many. He retired at age 34, with three championships and sitting top of the all-time leaderboard for total wins. At Lotus, it was a close fight for 2nd and 3rd in the championship. Fittipaldi beat Peterson by 3 points, but had two fewer mechanical DNFs, giving Peterson the higher performance rating based on points per counting race.

In the model simulation, Clark is predicted to take the fight right to the wire with Stewart. Note, however, that this is under the assumption that Stewart still skipped the final race following the death of his teammate, Francois Cevert. With the championship still in the balance, Stewart might have made a different decision.

Beyond 1973, the Lotus team tailed off in performance due to the abortive Lotus 76 project, to the extent that even a driver of Clark’s abilities would not be predicted to challenge for titles. By the time they became dominant again with the mastery of ground effects on the Lotus 79, Clark would have been past his best. It’s plausible that Clark would have simply retired at the end of 1973, aged 37, joining his compatriot Stewart.

Beyond 1973, the Lotus team tailed off in performance due to the abortive Lotus 76 project, to the extent that even a driver of Clark’s abilities would not be predicted to challenge for titles. By the time they became dominant again with the mastery of ground effects on the Lotus 79, Clark would have been past his best. It’s plausible that Clark would have simply retired at the end of 1973, aged 37, joining his compatriot Stewart.

In conclusion, had he avoided that fateful Formula 2 race on a wet day at Hockenheim and remained at the Lotus team from 1968-1973, Clark would almost certainly have won the championship in 1968, may also have won in 1970, and would have been at least in the championship hunt in 1971, 1972, and 1973. The results in some of those years hinge on car reliability, which was a very significant factor in the shorter championship campaigns of that era. In the model’s simulated scenario, Clark finishes his career as a four-time champion, with four 2nd places in the championship, as listed in the table to the left. A stellar career, much more befitting of Clark’s incredible talents than the two titles he ultimately achieved.

Lost American talents:

Donohue & Revson

Mark Donohue and Pete Revson going wheel to wheel in Can-Am.

Since the 1990s, cross-overs between the top US single-seater series (e.g., IndyCar) and Formula 1 have been generally unfavorable for the US side. Emerson Fittipaldi and Mario Andretti remained championship contenders in CART well into their late 40s, reflecting a lack of comparably talented younger drivers in the series. Mansell was an immediate success when he moved across to the CART series in 1993, whereas Michael Andretti was hopelessly off the pace when he moved in the other direction. Alex Zanardi was a fairly weak F1 driver during both stints, but was quite successful in CART. The only obviously great export from IndyCar to F1 in the 1990s was Jacques Villeneuve.

As I showed in last year’s junior driver analysis, today’s IndyCar grid is overall a much weaker field than today’s Formula 1 grid. If we go back to the 1960s-1970s, the balance of power is not so evident. Mario Andretti and Dan Gurney were both very strong F1 drivers who moved frequently between US and European series. Phil Hill also won a championship, albeit with very favorable machinery. In addition, there are two decorated US drivers who arrived in F1 late in their careers and were both killed in F1 cars. They are Pete Revson and Mark Donohue. Some believe they could have been among the top F1 drivers of the era.

Mark Donohue

Donohue was an extremely versatile and intelligent driver, who excelled in sportscars, sedans, prototypes, and single-seaters. His book, The Unfair Advantage, which chronicles every car he ever raced, is a classic part of motorsports literature. He dominated the Can-Am series in the early 1970s (a time when Can-Am cars approached and sometimes exceeded F1 pace) in partnership with Porsche and Penske. He also won the inaugural International Race of Champions, winning 3 out of 4 races in a field that boasted Fittipaldi, Hulme, Unser, Foyt, Revson, Petty, and Pearson.

Donohue didn’t debut in F1 until 1971, when he was 34. He started only one race that season and finished 3rd — the next driver to score a podium on debut was Jacques Villeneuve in 1996. Donohue attempted a return to F1 in 1974, but died aged 38 of head injuries following a crash caused by a tyre failure during the 1975 season.

Pete Revson

Revson first raced in F1 in 1964, but didn’t attempt a full season until 1972, by which time he was aged 33. In the meantime, he was a top competitor in North American series, including Can-Am and Trans-Am. In his first full season of F1, he was competitive with his ex-champion teammate Hulme. In his second full season, he won two races and outscored Hulme. Due to a strained relationship with McLaren team boss Mayer, and Emerson Fittipaldi joining the team, Revson moved to the Shadow team for 1974. He was killed early in the season by an accident caused by a front suspension failure.

How strong could Revson and Donohue have been if they had committed to F1 earlier in their careers? In the hypothetical below, I have imagined Revson continuing in F1 from his debut in 1964. In Donohue’s case, I have imagined him debuting in F1 in 1968 (aged 31), at the time when he was instead debuting in the top single-seater series in the US.

Both drivers’ projections have considerable uncertainty; especially Donohue’s, since he completed only 10 counting races in F1 (i.e., races without a non-driver DNF). Nonetheless, the projections indicate that both drivers would likely have been among the top 5-10 competitors on the grid. In Donohue’s case, it’s even likely that he would have been one of the sport’s best drivers in the early 1970s. In the right car, he very feasibly could have been an F1 champion. Revson was probably not quite at the same level of talent as Donohue, but nonetheless would have been a very strong competitor had he committed to F1 earlier.

Robert Kubica: the injury and the potential comeback

Kubica’s short but spectacular career in Formula 1 had the hallmarks of future success. Across 2006-2009 he was almost perfectly matched with the more experienced Heidfeld: the net tally was 29-28 to Kubica in qualifying, 25-24 to Heidfeld in races (excluding mechanical DNFs), and 150-137 to Heidfeld in points. In 2010, Kubica seemingly took his performance to a new level, establishing himself as a potential challenger to the sport’s elite. He dragged the Renault into positions it shouldn’t have been and some of his qualifying laps from that season remain among the finest I have seen. The model ranks him the 3rd best performing driver in 2010, the highest ranking in his career. He was perhaps on the cusp of something even greater.

Sadly, it was not to be. Kubica suffered a horrific injury in a rally accident before the 2011 season, leaving many unresolved questions. How would we have performed at Ferrari, where he was signed to drive in 2012? Alternatively, could he have taken the 2012 Lotus to the title, had he raced in Raikkonen’s place?

Kubica’s arm showing the extent of injuries from his fateful rally accident.

In the following years, Kubica demonstrated he had lost little of his speed, with an impressive switch to rally, motivated partly by his physical limitations in the tight confines of a single-seater cockpit. He won WRC-2 and then competed in the World Rally Championship. At the top level of rally, he showed occasional glimpses of speed, but was too inconsistent to achieve strong results. Recently, the Kubica story took a new twist, as Kubica prepared for a potential Formula 1 comeback. He narrowly missed out on a seat at Williams for 2018 to Sirotkin, but remains currently on the hunt for an open seat. If Kubica could recapture his 2010 form, he would be a welcome addition for almost any team. But realistically, even discounting effects of the profound injuries on performance, how competitive could a driver be after 7 years out of F1 racing?

These are questions we can attempt to answer with the f1metrics model. The graph below charts two predicted trajectories for Kubica. The green curve shows Kubica’s most probable trajectory if he had never experienced the 2011 injury and continued racing from 2011 onwards.

F1 driver performances tend not to systematically improve after four full seasons of experience, or after the age of ~26. In other words, Kubica was likely operating near the height of his powers in 2010 (the model actually thinks he had better than average form that year) and would most likely have maintained a similar performance level for up to a decade. In the most optimistic forecast (top of the green region), he might have challenged the very elite drivers (e.g., Hamilton, Alonso) for top performer in certain seasons. In the more probable forecast, he would have been a top driver, but not an all-time great.

The red curve shows how Kubica would be expected to perform following a 2018 comeback to the sport, based on average rates of improvement with experience across all the fitted data from F1 history, including past driver comebacks. Based on model fits to historical data, by the time Kubica would likely reach his maximum potential (around 2020-2022) he would be aged 37 and contending with age-related decline, meaning he likely wouldn’t ever quite attain his 2010 high point again.

As beautiful a story as a Kubica comeback would be for the sport, the model predictions aren’t overwhelmingly positive about this scenario. Note, however, that different drivers are known to improve at different rates and also undergo age-related decline at different rates, so there is a wide band of uncertainty on this prediction. Additionally, in these comeback predictions, there is no way of objectively estimating the performance impact of Kubica’s injury. It could certainly not improve his performance, but the degree of deficit remains in question. The red curve is thus a simulated best-case scenario, assuming zero impact of the injury on his performance.

The 2018 Williams driver line-up: Stroll, Sirotkin, and Kubica.

Would Kubica have performed better or worse than the current Williams drivers, Sirotkin and Stroll, if given the 2018 seat? A quick glance at last year’s driver rankings shows Stroll at 7.05 ppr, but that is potentially misleading. As I noted at the time, Stroll’s ppr was inflated by that outlier 3rd place in Baku, where he was on course to be beaten by Massa prior to Massa’s car failing. If the 3rd place is replaced with a mechanical DNF, Stroll’s 2018 performance rating drops to 5.6 ppr, which is probably more reflective of reality. Under that assumption, the 2018 Williams drivers are currently rated at 5.3 ppr (Sirotkin) and 6.3 ppr (Stroll). Referring to Kubica’s projected red curve above, we can see that the first point is at 6.3 ppr, rising to 7.0 ppr in the second season. These results suggest that Kubica would have performed at a similar level to Stroll and better than Sirotkin, with scope to improve from there. Beyond 2018, the comparison is complicated by Stroll and Sirotkin also improving with age and experience, but taking those factors into account still leaves Kubica with a probable small edge over Sirotkin up to 2022.

Now, let us return to the hypothetical scenario of Kubica never sustaining his injury — an oft-considered F1 hypothetical. Where would that have taken him?

First, we can assume that in 2011 Kubica would have raced for Renault (Lotus Renault GP) as planned, taking the seat that Nick Heidfeld and Bruno Senna actually filled. This was a difficult season for the team, as the R31 proved uncompetitive. A novel forward-exhaust concept did not pay off. Consequently, the team switched focus early to 2012 development, which ultimately paid dividends for them.

The model sees Kubica as likely the 4th best performing driver in 2011, narrowly ahead of Hamilton, who experienced his career-worst season. In the simulated season, Kubica scores an impressive 116 points for 7th in the championship (compared to Heidfeld’s 34 points and Senna’s 2 points with half a season each) — elevating the team to 151 points, nearly enough to overhaul Mercedes’ 158 points for 4th in the World Constructors’ Championship.

For 2012, Kubica had a signed agreement to join Ferrari, ousting Felipe Massa. This would have placed Kubica in a potential championship fight for the first time, but also in the unenviable position of facing Alonso as a teammate.

For 2012, Kubica had a signed agreement to join Ferrari, ousting Felipe Massa. This would have placed Kubica in a potential championship fight for the first time, but also in the unenviable position of facing Alonso as a teammate.

Kubica and Alonso: destined to be teammates in 2012, if not for the injury.

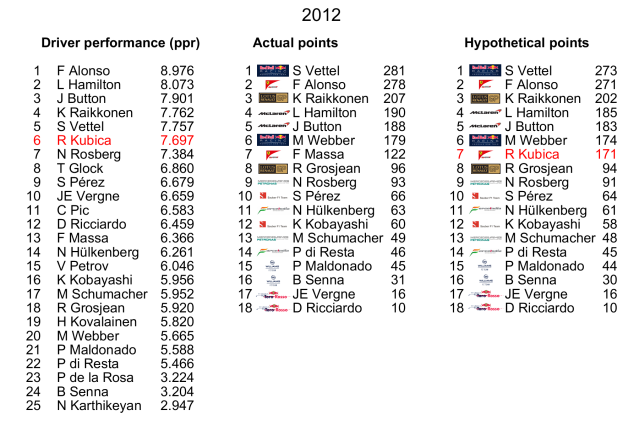

In the model’s simulation of the 2012 season, Kubica scores 171 points — significantly more than the 121 points Massa scored, but not enough to drag the unwieldy F2012 into championship contention. Alonso still loses the title narrowly to Vettel, but note that the model does not implement team orders. While Massa was able to provide a boost to Alonso’s chances in the final two rounds of 2012, the rest of the season he was largely a non-entity, unable to extract enough from the car to take points from Vettel or directly aid Alonso. A faster driver in the second Ferrari would have opened additional strategic options and could have selectively taken points from Vettel but not Alonso — perhaps enough to change the title outcome.

There’s an additional wrinkle to this story, which is the 2012 Lotus-Renault. The E21 (the result of Renault’s early switch to 2012 development) was a highly competitive car, fast enough to take Grosjean to 8th in the championship in his first full season, despite crashing out of 6 of the 20 races and being banned from another. If, for whatever reason, Ferrari had not taken the option on Kubica, he may have started the season for Lotus.

It is worth speculating whether a quicker driver could have challenged for the title in the E21, particularly considering that Raikkonen was on return from a 2-year break and was soundly beaten when facing Alonso and Vettel in subsequent seasons. The number of races where Lotus came tantalizingly close to a stronger result adds substance to this argument.

Fact: If we imagine a driver who finished each race 10 seconds quicker than Raikkonen in 2012, they would have won the championship (273 points to 269 points).

On the other hand, to Raikkonen’s credit, he was extremely effective in managing the 2012 Pirelli tyres (often sacrificing qualifying performance for a better race strategy), and finished every race.

Looking at the first column (Driver performance) in the 2012 simulation above, the model does not see Raikkonen as 2012’s strongest performing driver, but it does rate his performance highly: 4th best, and very similar to Kubica’s predicted performance. In other words, the model thinks that Kubica would have scored a very similar points tally to Raikkonen, had he been in the Lotus seat that year instead.

Overall, these predictions support the prevailing view of Kubica as a potential top driver who would have challenged anyone for wins in the right equipment, had his career not been so dreadfully curtailed. But it is a step short of putting Kubica among the generation’s all-time greats.

For Clark’s 1970 season, did you consider that Lotus withdrew from the Italian Grand Prix after Rindt’s death, and didn’t return in Canada, only at Watkins Glen, thus Clark would have only had two races more than Rindt in 1970. Did you use two extra races for Clark or four?

Good question! In this hypothetical I have assumed Lotus would continue to race in those events, which I think makes some sense given the WDC would still have been up grabs for Clark, but it’s definitely open to debate.

Why is everyone catching up to the best performer so fast? Will the races of the future be fought between drivers of barely distinguishable skill levels? 🙂

I think it’s basically because the grid is improving over time — this trend has become much more evident since I incorporated the age and experience effects into the model.

Drivers today are coming from a larger talent pool with better training, and there are no talentless pay-drivers like we had in the 2000s and earlier. Those driver were genuinely 2-4 seconds slower than the best drivers, whereas today I’d expect the gap to be more like 1-1.5 seconds. I think that trend will probably continue as drivers continue to approach the human performance ceiling.

I always thought that there was an increase in driver quality in the early 2000s, but yes, there was still a bunch of unpromising drivers such as Yoong, Sato, Firman, Kiesa, Baumgartner, Bruni, Albers, Monteiro, Ide, etc., who were most likely somewhere in the bottom of the rankings. Also, the first generation of Toro Rosso drivers wasn’t very good (interestingly, Alguersuari and Buemi are considered much weaker than Vergne by the model, even though Helmut Marko only regrets losing Buemi). Nowadays there are no really weak drivers anymore. Even Sirotkin and Stroll are doing a decent job I think, even though they may be quite slow. I have some qustions for you.

How much do you think is the effect of telemetry on this performance convergence? Nowadays drivers can learn from each other, which gives them a chance to get closer to a strong teammate than, say, in the 1980s. Or might this convergence be a result of the high-deg tires, who act as a performance ceiling?

Is the current generation of F1 drivers flattered in the model by the difficulty of crashing out nowadays (as a result of long runoff areas and drivers not pushing too much during the race)?

Is the difference between the fastest and slowest driver really over a second? Last year, Hülkenberg was about a second faster than Palmer, which seems to indicate this is correct, but back in 2009 the gap between the fastest and the slowest driver usually was no more than two seconds, which suggests that the difference between first and last on the grid was mostly down to the driver and not the car, especially as the worst performer (Badoer?) was really bad that year.

I think it’s a combination of a few of the factors you’ve mentioned. Definitely telemetry has helped drivers to improve. Look back to how remarkable Schumacher’s multiple speed dials was considered and contrast that to what even junior series drivers have now!

More recently, I think the tightening up of the super license system is a big factor. It’s virtually impossible for a driver such as Yoong to make it through. Even a “bad” pay-driver such as Stroll is pretty decent these days, as you say.

I do believe the difference between Hamilton and say Sirtokin (this year) or Stroll (last year) would average around a second. As a couple of ballpark figures:

* Massa averaged 0.35% slower than Alonso as teammates.

* Stroll averaged 0.96% slower than Massa as teammates.

On that basis, I seriously doubt Stroll would have gotten within a second of Hamilton or Alonso in equal equipment on more than a few occasions in 2017.

Regarding 2009, the cross-team comparisons are a bit tricky due to the fuel format used for qualifying. But nevertheless I agree there was probably at most a second between best and worst drivers. It was a truly remarkable season, with nobody that I would consider a real pay-driver.

That makes sense but damn, son… It’s like the field median covered the difference from Charles Pic skill level to Lewis Hamilton skill level in 5 years. Schumacher was worse than Petrov in 2012? Ouch! I was kinda convincing myself he’s almost Rosberg level. Alonso seems head and shoulders above everyone else. What happened to him in 2007? Surely rookie Hamilton was a worse driver than experienced Hamilton is.

Schumacher had a lot of bad luck in 2012, so take his ppr with a grain of salt that year. With a careful analysis of misfortune, Rosberg and Schumacher usually come out dead even that year.

2007 Hamilton is indeed ranked lower than Hamilton today. 2007 Alonso is rated very poorly by his standards.

Hi, Dr. Philips. What a long wait you’ve made us endure for this article! Hopefully we won’t have to wait as long for Pt. 3. I have some questions and suggestions:

1. How will you tackle the remaining parts of this series? Will you stick with prematurely killed/injured drivers, or will you take on the hypothesis of drivers actually getting the equipment they deserve (i.e. Alonso)?

2. How will you rate the current grids of IndyCar, Super Formula, and F2? Which is the best in terms of quality, compared to F1?

3. Does the PPR method work with other championships with significantly different points system, such as IndyCar? Also, does it work with other disciplines, like rallying or motorcycle racing?

Apologies for the long wait 🙂 I promise to keep things more interesting in the off-season!

1. What I have planned for the moment is a mix of both those themes. There will definitely be a few cases where I consider career branch points (e.g., Alesi).

2. That’s a cool question. I’ve thought a little about it, but haven’t done a formal analysis. It’s something I might put together with the junior driver rankings one year if I get the time.

3. I think the method would absolutely generalize to other series, at least circuit series with similar championship / team formats. So that would include IndyCar and I think also MotoGP. I’ve sought datasets for those two, but haven’t found a complete one yet that would allow me to easily apply the distinction of driver vs. non-driver DNFs. So that’s the main sticking point for now. The hard step is always pulling the data together (it was a months long project to check and double-check all the cases in the F1 championship). After that, the modeling is relatively straightforward!

Are there also imaginable cases where a driver’s career could have looked different, if only the driver had debuted earlier instead of retiring later (for whatever reason)? For example, do you think it is interesting to test what Damon Hill could have achieved had he made his debut in 1984?

That’s a fascinating question. I could certainly try to answer a few cases like that. Just let me know if you think of others you would like me to consider in the upcoming parts and I will try to include them!

Carlos Reutemann I think could qualify here, Mario Andretti, Jacques Laffite and John Surtees may be interesting too. After re-reading Mika Salo’s entry on the all time list, he as well might be worth investigating, if given the career path of Mika Hakkinen.

Partially connected to this type of question, do you think it would be worth investigating what could have happened if certain drivers could have signed by top teams in an earlier stage of their career? Three drivers are coming to my mind (coincidentally they were regarded as Nr. 2 drivers as well, but that’s not what I’m interested in), and after the beginning of their career they stucked in inferior cars only to be picked up by top teams later, maybe a bit too late (this is what I’m interested in, and has a general idea to support this hipothesis, but nothing more). Rubens Barrichello in his 8th, Mark Webber in his 8th, Giancarlo Fisichella in his 10th season was able to take their hands on title contender constructions. They seemed more than solid when extracting everything from their midfield cars, but struggled at top teams, obviously hindered by their Nr. 1 status teammates, but still. Unfortunately Mark Webber is the only one of them that is known to have almost landed at a top team, at Renault for 2005 instead of Williams, which was his 4th season, more ideal according to my opinion to arrive.

Thank you for the article, it was a really fascinating read, and the Kubica section is really timely, as his name is still in the pot. The fact that more teams gave him a chance to test their car but none of them took the risk to put him behind a wheel for a whole season and your numbers are absolutley supporting each other, and put an emphasis on the enermous uncertainty wether to sign him or not. His best chance I believe is past him, he could have easily replaced Palmer at Renault last year for the last couple of races. A marketing fairy tale for Renault meanwhile they could have been evaluating him without risking too much, but as they set eyes for P6 on the constructors championship, and were able to put a safe pair of hands (no pun intended) on the wheels, he lost out on that opportunity. Although Williams is tend to promote their reserve drivers, their crucial financial situation might force them to ignore Kubica again, so the development role at Ferrari seems more likely.

I would love to see what you would make of the career of Jochen Rindt, had he survived that crash in Monza and continued racing.

On a side note: Heinz Prüller, an Austrian TV-personality who was responsible for F1 TV coverage until the late 2000s, always argued, that Rindt would have quit and managed F1 alongside Bernie Ecclestone. Apart from Rindt’s racing career I am also always wondering what F1 would look like if an Ecclestone/Rindt-duo would have been in charge for decades.

Amazing work again, such an underrated site.. After reading about Kubica, where do u rank Raikkonen now in all-time greats list? In 2014, u ranked him 14th, but obviously it was before he got demolished by Alonso and Vettel. Does it remain the same, or there is a massive decline in his rank?

Reblogged this on AF1@F1.

Something I think that would be great to see is to take every driver in the model currently under the age of 35 or so, and rank them based on what the model expects from them in 1, 3, 5, 10 seasons. Who does the model predict will be the best driver of the “new generation” out of Verstappen, Gasly, Ocon, etc.

[…] With Sirotkin and Ocon losing their seats, we will gain Kubica and Russell to the 2019 grid. As my recent historical hypothetical showed, Kubica would be predicted to perform at a similar or slightly higher level than Stroll or […]

Great work 🙂

I hope you’ll model Jules Bianchi hypothetical career.

I dn’t think that’s possible on account of lack of races/teammates he had in his short career.

[…] https://f1metrics.wordpress.com/2018/11/09/historical-hypotheticals-part-ii-clark-donohue-revson-kub… […]

[…] https://f1metrics.wordpress.com/2018/11/09/historical-hypotheticals-part-ii-clark-donohue-revson-kub… […]

Hi, could you do the same exercise with François Cevert after 1973 season ?

Great suggestion, I will include that!

Great article as always, though I do believe that your model overrates Rindt due to Graham Hill driving a privateer Lotus in 1970 after his gruesome accident at Watkins Glen in 1969 (he couldn’t get out of the car in the South African Grand Prix, for instance). But that just might be my inner Jim Clark fanboy that protests.

Another interesting case is Ricardo Rodríguez, the younger brother of Pedro who died at only age 20 (!) in 1962. He did not drive a lot of races, but showed a great deal of promise. Would it be possible to create a similar scenario for him?

Other interesting scenarios include Stirling Moss, who was scheduled to drive for Ferrari in 1962, not ending his career after his Goodwood crash and Alberto Ascari surviving his 1955 crash.

As always, an interesting read! I look forward to your next article!

[…] Part II (Kubica, Clark, Donohue, Revson) […]

[…] Historical hypotheticals: Part II […]

[…] Part II (Kubica, Clark, Donohue, Revson) […]

[…] Part II (Kubica, Clark, Donohue, Revson) […]

[…] comeback many fans had hoped for, but it was the performance many of us expected, and in line with my prior model predictions back in 2018. Considering the incredible odds that Kubica had to face — lack of recent experience, massive […]