Recent years in Formula 1 have been challenging for viewers, with Red Bull dominance in 2011 and 2013, followed by Mercedes dominance in 2014 and 2015. Periods of team dominance are not new to Formula 1, since differences in car performance have always trumped differences in driver performance. Nevertheless, the level of dominance achieved by Mercedes in 2014 and 2015 raises the question of whether there has ever been such a sustained advantage by any team. It also leads one to ask which sporting factors enable team dominance to occur.

There have been many past rankings of the most dominant teams in Formula 1 history. However, these rankings were based on statistics such as percentage wins, percentage poles, percentage points, and percentage 1-2 finishes. These metrics do not account for the team’s drivers. McLaren in 1988 and Mercedes in 2014 were helped by having two strong drivers. One wonders, for instance, how the 1992 Williams might have performed with Senna and Prost at the wheel.

Using my mathematical model, we can ask which teams would have beaten their nearest rivals by the greatest margins if all teams in the field had equally good drivers, with two drivers per team at all races. This analysis takes mechanical reliability into account, which is why cars like the outrageously quick but fragile MP4/20 do not quite make the list. The analysis is based on race finishing positions, not time differences (which may be affected by safety cars or drivers coasting), qualifying positions, or any other metrics. The model uses a standardized scoring metric, based on the 10-6-4-3-2-1 system, allowing direct historical comparisons, as described previously.

Note: This article was previously included in my article A Reconstructed History of Formula 1, but is now presented as a companion article for improved readability. The model rankings have also been updated here to incorporate data up to and including Japan 2015.

The 20 most dominant teams

For each team in the list, I have reported the predicted advantage in points per race (ppr) over the next best team. As a hypothetical example, a team that finished 1-2 in every race would score 16 ppr, while a rival team that finished 3-4 in every race would score 7 ppr. This would give the leading team an advantage of +9 ppr. The most dominant car in history actually scores something close to this: +8.84 ppr.

20. 1955 Mercedes (+2.93 ppr)

In 1954, Mercedes returned to Formula 1, attracted by the new engine formula, which allowed 2.5L naturally-aspirated engines or 0.75L compressed engines. Mercedes arrived mid-season with the naturally-aspirated W196, poached Fangio from Maserati, and won 4 of the 6 races they entered. By 1955, the team were running at full steam. The W196 engine, which featured direct injection and desmodromic valves, was boosted from an initial 256 horsepower to 290 horsepower, giving a slight advantage over Ferrari and Lancia.

With Fangio and Moss at the wheel, the team won 5 out of 7 races in 1955, with one of the other two races being Indianapolis. Castellotti, who was 3rd in the championship for Scuderia Lancia, scored less than a third of Fangio’s points.

19. 1970 Ferrari (+3.01 ppr)

The 1970 Ferrari has the ignominious honor of being rated the best car to win neither the drivers’ title nor constructors’ title. This was partly due to Jochen Rindt’s brilliant performance at Lotus, winning 5 of the first 9 races before tragically dying in qualifying for the Italian Grand Prix. Rindt’s teammate John Miles never looked competitive and he was soon pushed out by Colin Chapman for the young talent Emerson Fittipaldi, who scored a crucial win at Watkins Glen in only his fourth race to keep Lotus ahead in the constructors’ championship.

Ferrari were recently rejuvenated by the injection of $11 million from Fiat, who bought half of the company in 1969. For 1970, they had developed a new car and a new engine (the Flat-12). However, their title chances were damaged by entering only one car in four of the year’s races. This was less of an issue than it would be today, since only the top-placed car scored constructors’ championship points in each race, but their lone car DNFed in three of those races, costing them valuable points.

18. 1967 Brabham-Repco (+3.31 ppr)

Formula 1 moved to a new engine formula in 1966, doubling the volume of naturally-aspirated engines from 1.5L to 3.0L. The result was a total upheaval of the existing team hierarchy. With their previous engine supplier, Coventry Climax, withdrawing from the sport, Lotus, Brabham, and Cooper all needed new engines. BRM developed a new engine of their own, but it proved to be massively overweight. Cooper partnered with Maserati, but the engine was unreliable. Lotus were left using 2.0L Climax and BRM engines as a stopgap, before beginning a new partnership with Ford for 1967. In the following years, Lotus and Ford revolutionized the sport, but in 1967 the development program was premature and the Lotus-Ford was quick but fragile and difficult to drive.

The engine-centric Ferrari team could have benefited most from the new regulations, but they had their priorities elsewhere, trying hard to beat Ford in the World Sportscar Championship. Rather than building a new engine, they took their successful 3.3L sportscar engine and modified it to 3.0L. The result was a relatively heavy, underpowered engine. Combined with their outdated chassis design, Ferrari entered one of the least competitive periods in their history, not helped by losing their star driver Surtees and suffering the death of Bandini and serious injury to Parkes.

The winner in all of this was Jack Brabham, who saw potential in his existing relationship with the Australian automotive company, Repco. When the regulation change was announced in 1963, he approached them to build a new engine. The result was the Repco 620 V8. While the engine delivered only about 310 horsepower (compared to the 330-360 horsepower of its main rivals), it was smaller, lighter, more efficient, and more reliable. The result was the WDC and WCC in two consecutive years, with Hulme and Brabham finishing 1-2 in the championship in 1967.

17. 1953 Ferrari (+3.57 ppr)

During 1952-1953, the Formula 1 world championship adopted Formula 2 regulations to boost the number of entrants, following the withdrawal of Alfa Romeo, while the governing body waited for major manufacturers to develop new cars for the 1954 regulations. Only Ferrari built a new car specifically for the Formula 2 regulations. It debuted at Modena in the 1951 Formula 2 season, with Ascari winning by a lap over Gonzalez in the Ferrari Tipo 166.

By 1953, Maserati’s A6GCM had partly closed the gap to the Ferrari Tipo 500, taking two poles and one (lucky) win with Fangio at the wheel. However, the Tipo 500 remained the dominant car, taking 7 wins in 9 races to propel Ascari to his second consecutive championship. With equal machinery, the model thinks Ascari would have narrowly beaten Fangio to the title.

16. 2007 Ferrari (+3.71 ppr)

As discussed in the 2007 season review, the model considers the F2007 a significantly better car than the MP4/22. While the advantage swung between the teams on different weekends, Ferrari had the advantage more often, evidenced by their 9 poles, 12 fastest laps, and 9 wins in 17 rounds. With Michelin exiting the sport, Ferrari were anticipated to gain an advantage through their long-term relationship with Bridgestone, and so it proved. McLaren were surely helped by the stolen technical information they received from disgruntled Ferrari employee Nigel Stepney, but were still on the backfoot in terms of performance for most of the year. Ultimately, McLaren narrowly lost both titles, although the closeness of the fight was a huge credit to the quality of their drivers — arguably the two greatest drivers of their generation. Later, we saw how each of Ferrari’s 2007 drivers measured up to Alonso in equal equipment, albeit with some team favoritism towards Alonso. The results were extraordinarily lopsided — even more so than Schumacher vs. Barrichello.

15. 1982 Ferrari (+3.81 ppr)

1982 was always set to be an interesting year, with the FIA repealing their previous ban on skirts and restrictions on ride-height, allowing greater use of ground effect again. The FISA-FOCA wars were also continuing, as turbo and naturally-aspirated engines battled it out on track. Given Ferrari’s appalling recent results, including 10th in the championship in 1980, few could have suspected that they would produce such a dominant car. Harvey Postlethwaite led an overhaul of the 1981 model, yielding much improved aerodynamics. The upgraded turbo engine was extremely powerful and reliable, producing around 600 horsepower in race-trim. Meanwhile, Williams were losing both Jones and Reutemann, while Brabham were suffering teething problems with the move to BMW power.

Undoubtedly, Ferrari should have easily won both titles that year. They won the constructors’ title despite losing both their star drivers, and only starting 8 of the 16 rounds with two cars. In equal equipment, however, the model ranks Pironi’s performance only the 14th best that year, and ranks Pironi the 122nd greatest driver of all time. Had he won the 1982 championship, as he was surely on course to do, he would be ranked the second-weakest champion in history by the model. This is a product of the fact that Pironi never outscored a teammate, including Depailler, Jarier, Laffite, and Villeneuve. Gilles Villeneuve is sadly unranked in 1982, due to a lack of completed races.

Rosberg’s Williams was never the quickest car and he won only a single race on his way to the title, but he was nevertheless a deserving champion given the machinery at his disposal. The model suggests an even more deserving champion: Elio de Angelis, who partnered Mansell at Lotus, scoring 23 of the team’s 30 points.

14. 1998 McLaren (+3.93 ppr)

In 1997, Adrian Newey moved from Williams to McLaren. The next year saw a huge power shift in that direction. In 1998, reigning champions Williams took only 3 podiums and 0 wins, while McLaren went from 4th in 1997 to winning both titles and 9 out of 16 races in 1998. Not all of that can be credited to Newey. The 1998 season brought a significant change to the technical regulations, with cars narrowed and grooved tyres introduced. Mercedes were also going from strength to strength, while the previously dominant Renault were bowing out of the sport.

To quote Mika Hakkinen,

As soon as my team-mate David Coulthard and I drove our McLaren-Mercedes MP4-13s out onto the Albert Park circuit that year, it was apparent that our cars were the class of the field. The MP4-13 was an utterly brilliant design, the work of Adrian Newey and his team of very clever men, and it was soon clear that David and I would achieve that much prized racing feat, the front-row lock-out. We duly did just that, I in P1 and DC in P2. The margin of our superiority was staggering.

Some of McLaren’s huge advantage was undermined when a third pedal — a system called “Brake steer” — was discovered in the cockpit and Ferrari protested. This pedal allowed the driver to independently control one of the rear brakes, helping to turn the car into corners. McLaren, however, remained the team to beat. For a third year running, Schumacher put in giant-killing performances to take wins from Newey-designed cars, including his memorable charge in the third stint at Hungary 1998 to gain 20 seconds in 16 laps, but it was not enough to take the title.

In equal machinery, the model thinks Schumacher would have stormed to the 1998 title, with Hakkinen narrowly beating Hill, Trulli, Alesi, Villeneuve, and Frentzen for runner-up.

13. 1986 Williams (+4.05 ppr)

Williams and Honda began a partnership at the end of 1983, which slowly gained momentum over time. In 1984, Williams-Honda were 6th. In 1985, they were 3rd and won the last three races. By 1986, the Honda powerplant was generating 900 horsepower in race-trim, equaling Renault and BMW, and bettering McLaren’s TAG engine by 50 horsepower. McLaren were also now into their third season running iterations of the MP4/2 chassis, which won them the 1984 and 1985 titles. By 1986, the age of this design was showing and it was significantly beaten for pace by the new Williams FW11.

Up against the might of Williams, Prost drove a remarkable year to take the title fight to the last race and win the championship in dramatic circumstances. The model ranks the 1986 Williams the most dominant car in history to not win the drivers’ championship. Honda and Piquet were furious with Williams for dropping the championship with such a clear car advantage and after years of progressive development. Both believed that the team should have backed Piquet, whom Honda considered the number 1 driver. Thus began a schism that ultimately led to Honda leaving for McLaren in 1988.

12. 1987 Williams (+4.28 ppr)

In 1987, Williams went one better, easily winning both the constructors’ and drivers’ titles. McLaren lost chief designer John Barnard in late 1986 and their new MP4/3 was no match for the upgraded FW11B. Williams continued to be supplied with the much-coveted Honda engines. Lotus now had a Honda customer contract too, but it only allowed them to run 1986-spec engines.

While Piquet and Mansell dominated the drivers’ championship, the model thinks they would have been 4th and 5th in equal equipment. Instead, it considers Senna the most deserving champion, with Prost 2nd, and Cheever 3rd after his impressive performances in the uncompetitive and unreliable Arrows A10, which he wrestled into the points on 4 of the 7 occasions it didn’t break down.

11. 1988 McLaren (+4.95 ppr)

Statistically, the MP4/4 remains one of the most dominant cars in history, with an unmatched record of 15 wins in 16 races. Honda developed a new engine and McLaren a new chassis to address the new turbo boost limit of 2.5 bars and the new fuel limit of 150kg. Since 1988 was the last year of turbo engines, most teams chose not to develop completely new cars, leaving them massively outdeveloped by McLaren-Honda. The MP4/4 would not have been quite so dominant without Senna and Prost behind the wheel, but it was still undoubtedly an extremely dominant car. Had Warwick and Cheever switched seats at Arrows with Senna and Prost at McLaren, the model predicts McLaren would still have won both the constructors’ and drivers’ titles.

10. 1952 Ferrari (+5.01 ppr)

Now we begin to enter the realm of cars that almost drove themselves to victory. With a car advantage of +5 ppr, a driver like Sergio Perez would be expected to beat Schumacher or Alonso at their peak driving in the season’s next best car.

Ferrari dominated throughout the 1952-1953 Formula 2 era, but their advantage was at its greatest in 1952. Manufacturers Alfa Romeo and BRM withdrew after 1951, and Mercedes were waiting for the new regulations in 1954, leaving Ferrari peerless. With Fangio badly injured, Ascari enjoyed an easy first title. His 6 wins from 8 races remains the highest percentage of wins achieved by a driver in any Formula 1 season.

The Tipo 500 was at least a year ahead of the competition in development. It won 7 of the 8 races (including six 1-2 finishes), the one exception being Indianapolis, which Ascari did attempt, but he retired with a mechanical failure while running 12th. The Tipo 500 engine was producing around 180 horsepower, leaving the competition badly outgunned. The nearest competition produced an estimated 150-160 horsepower. The main threat should have come from Maserati, but their A6GCM, which produced around 190 horsepower, was not ready until the final round.

9. 1992 Williams (+5.11 ppr)

Mansell is the only driver lucky enough to have raced three cars on this list. Of the three, the Williams FW14B was undoubtedly the most dominant, and it was the car that finally delivered him an uncontested championship. The car was a technical triumph, combining Newey’s aerodynamic design with an unprecedented level of electronic sophistication and Renault power. Mansell, now an active-suspension convert after earlier struggles with the system at Lotus, won 9 races. Patrese was rarely competitive and was ordered to yield to Mansell in France on one of the rare occasions when he was leading.

Nobody else that year had a hope. Senna was in relatively poor form in a very distant McLaren, and despite his known brilliance in qualifying, he managed to prevent Williams taking pole in only 1 of the 16 races. Meanwhile, Alesi (the model’s pick for most deserving champion, just ahead of Schumacher and Mansell) must have been ruing his decision to drive for Ferrari, who produced their worst car in over a decade.

The 1993 Williams FW15C was a natural evolution of the FW14B and in some respects it was the most advanced Formula 1 car in history, with an even better refined active suspension system, traction control, automatic gear shifts, and ABS brakes. In qualifying, it was equally dominant, allowing Senna only 1 pole in 16 races. However, it’s interesting to note that the model considers it significantly less dominant than the 1992 Williams, and it falls just outside the top 20 list. The 1993 McLaren MP4/8 was at a visible 80 horsepower deficit to the Williams-Renault, but it was a brilliant design in many other respects, matching Williams in its technological advancement. Michael Andretti’s struggle to adapt to Formula 1 did the car a great disservice. The traction control system and chassis were especially well suited to wet weather and McLaren’s upgrades brought them on terms with Williams in the final three races when Senna was paired with Hakkinen.

8. 2011 Red Bull (+5.65 ppr)

For the 2011 season, the FIA introduced new aerodynamic regulations, designed to ban the use of double-diffusers. DRS was also introduced, along with Pirelli tyres. With engine development frozen, all engines producing similar power, and all teams running the same tyres, aerodynamics was the key performance diffentiator between teams. In this environment, Adrian Newey was likely to excel. The result was the RB7, one of the most dominant cars in history.

One of the car’s chief strengths was its use of off-throttle blowing of the diffuser, which greatly increased downforce during corner entry. Vettel used this feature to incredible effect, taking 15 poles and 11 wins. Webber achieved much less with the same car, taking only 3 poles and 1 win, and even scoring fewer points than Button in the heavily outmatched McLaren. With two top drivers in the Red Bull car, 2011 would have been even more of a whitewash, although it might at least have been an entertaining championship battle.

7. 2015 Mercedes (+5.89 ppr)

When teams become dominant, they often maintain a large advantage for multiple seasons. This is simply because it takes time for other teams to catch up in development or for the rules to be changed in another team’s favor. With an almost static rule-set, a dominant engine, and extreme limitations on engine development, it was predictable that Mercedes would remain on top in 2015. While Ferrari made inroads over the winter, Red Bull and Renault slipped further behind. Mercedes also stretched their advantage over Mercedes-customers Williams, suggesting an impressive rate of continued chassis development on the W06.

In qualifying, Mercedes have looked even more dominant than last year. Up to Japan, they have taken pole position in all but one race. The car’s reliability has also improved since 2014. However, the car’s advantage has been partially undermined by poor starts due to inconsistent clutch behavior and strategic errors. On occasion, Ferrari have also looked equally quick in race-trim, or even quicker in Singapore, something that seemed highly improbable in 2014. The chances of anyone beating Mercedes remain slim. The only question now is how many years the dominance can last.

6. 1996 Williams (+5.91 ppr)

In the early 1990s, Williams had dominated via the strength of their aerodynamics, electronics, and exclusive works partnership with Renault. By 1996, two of those advantages were gone. Electronic driver aids were banned for 1994, and from 1995 the Renault works deal was shared with chief rivals Benetton, who won both 1995 titles. In 1996, many of Benetton’s key personnel moved with Schumacher to the ailing Ferrari team as part of Jean Todt’s plan to take the team back to glory.

The FW18 was a successful evolution of the previous year’s FW17, both faster and more reliable than its predecessor. Lead driver, Damon Hill, duly won the championship, but was pushed further than expected by his impressive rookie teammate Jacques Villeneuve. Together, they took 12 poles and 12 wins in 16 races. Even at his most brilliant, Schumacher could provide only occasional resistance, including his brilliant win at Catalunya. Such was the dominance of the 1996 Williams that it led many fans of the era to question Damon Hill’s status as a world champion. To quote a 1996 article by David Tremayne, titled ‘Why the car is the star’,

No one is suggesting that Damon Hill or Jacques Villeneuve have simian traits, but there is not a rival who does not believe that he would be world champion if only Frank Williams would stick him in one of his cars. Tinged with unbecoming shades of green, rivals can only snipe and suggest that it is not Hill’s skill that has won him the first three races of this season, but that the car is the star.

The model considers all drivers of that era a considerable distance behind Schumacher, but Hill is close to the best of the rest, ranked the 2nd best performing driver in 1994 and 1996. In the all-time driver rankings (which are continually slightly changing as new data arrive), the model currently ranks Damon Hill 21st of the 32 historical champions and Villeneuve 25th.

5. 2004 Ferrari (+6.07 ppr)

Schumacher’s 2004 season could be likened to Vettel’s 2013 season. Two years previously (2002 and 2011), the same driver and team had crushingly dominated. This was followed the next year (2003 and 2012) by a nail-biting championship battle. In both cases it was a false dawn of a new era, and the previously dominant team returned to winning ways again. Ferrari’s crushing advantage from the first race of 2004 came as a particularly rude shock to viewers, due to the team sandbagging throughout winter testing.

The Ferrari F2004 was a masterpiece and remains probably the fastest circuit racing car ever created. Many of the lap records it set have never been beaten, despite its grooved tyres designed to reduce grip. The only consistent challenge in 2004 came from Button at BAR, but he still ended the season winless, and his teammate Sato finished only once on the podium. Meanwhile, the Williams-BMW partnership was collapsing and McLaren were struggling to recover from the disaster of their MP4/18 project. With little competition, Ferrari won 15 of the 18 races, including eight 1-2 finishes. The utter dominance of the car was emphasized at Monza, when both Schumacher and Barrichello found themselves trailing the pack at the start of the race due to a spin and an early pit-stop, respectively. Both drivers easily drove through the field to finish 1-2.

4. 2002 Ferrari (+6.54 ppr)

Success with Ferrari was a long time coming for Schumacher, but certainly well worth the wait. After four years without a championship, he won five in a row. The first title in 2000 was largely down to Schumacher’s scintillating work behind the wheel. Indeed, the model rates the McLaren a slightly better car that year. By 2001, all elements of the Ferrari dream team had clicked, producing undoubtedly the year’s best car. With Hakkinen seemingly demotivated and suffering poor luck, Schumacher easily won his fourth drivers’ title, almost doubling runner-up Coulthard’s points.

In 2002, McLaren joined Williams in running Michelin tyres. This left Ferrari as the only realistic championship contenders on Bridgestone tyres and with Schumacher as the obvious team leader. Bridgestone could now organize their efforts around a single team and a single man, designing tyres to maximize his chances of winning the championship.

Ferrari had also developed a revolutionary new car, the F2002, which improved on the F2001 in literally every area. It included periscopic exhaust exits and an extremely light titanium gearbox. Despite their extensive testing schedule, Ferrari were still developing the new car at the beginning of the 2002 season, and so delayed its deployment until the third race of the season. From there to the end of the season, Ferrari won 14 of 15 races, for a total of 15 Ferrari wins in 17 races, including nine 1-2 finishes (bettered only by the 2014 Mercedes and 1988 McLaren). By the fifth race of the season, it was already clear that Schumacher would be uncatchable, which is partly why fans reacted so negatively to the infamous team orders at Austria.

3. 2013 Red Bull (+6.90 ppr)

The 2013 season started promisingly, with 5 different winners in the first 10 races, but a tyre controversy ultimately handed Red Bull an absurdly large advantage. In the first half of the season, Red Bull were still clearly the best team and Vettel had a 38-point lead, but when track conditions were in their favor, Mercedes seemed occasionally capable of challenging Red Bull. The problem was that the Mercedes W04 was extremely hard on tyres. Meanwhile, controversy was brewing. Mercedes had performed an illegal private test with Pirelli shortly before winning two races. Pirelli tyres were also puncturing at an alarming rate, partly due to teams running tyres on the opposite sides of the car from those intended by Pirelli, despite warnings about the practice. Under intense criticism, Pirelli made major modifications to the tyres between Canada and Hungary, and the FIA banned the swapping of left-side and right-side tyres.

The effects of these changes on the RB9’s competitiveness were immediate and striking. Vettel won the following 9 races in extremely dominant fashion, setting a new record for consecutive wins by a driver (equaled by Ascari across 1952-1953 only if one excludes Indianapolis, which Ascari did not attempt in 1953).

Much like 2011 or 1992, this was a year in which a dominant team had only one driver performing at a high level. While Vettel won 13 races and took 9 poles, Webber took 0 wins and 2 poles. The model thinks almost anyone on the 2013 grid could have performed as well as Webber did in the RB9, ranking Vettel the year’s 2nd best performer and Webber only 19th. Webber was certainly not helped by his poor qualifying performances and starts, both of which were particularly detrimental in a car that was designed to lead from the front.

It is interesting to observe Red Bull’s decline from 2013 to 2014. One could speculate that Red Bull and Renault over-invested in the 2013 season, achieving enormous dominance at the cost of their preparation for the next rule cycle.

2. 2014 Mercedes (+7.46 ppr)

Ranked just ahead of the most dominant Red Bull is last year’s incredible Mercedes W05, which won 16 of the 19 races, including eleven 1-2 finishes. Without driver error in Belgium or a mistimed safety car in Hungary, it could easily have been 18 wins. The car’s advantage was staggering, allowing the drivers to coast to victory while sometimes still a second per lap quicker than the opposition. Unless Mercedes encountered serious problems, there was simply no chance of any other team winning a race. To give some perspective on the size of the Mercedes advantage in 2014, we can ask the model to rerun the championship with the same teams and drivers, but with the Mercedes drivers, Hamilton and Rosberg, swapped with the Sauber drivers, Sutil and Gutierrez. The predicted drivers’ championship results are below.

Although the Sauber drivers were rated the two worst performing drivers of 2014 by my model, Mercedes is still predicted to win both the 2014 drivers’ and constructors’ titles, albeit with a much closer fight from Ricciardo. While the W05 could have won with almost any drivers, Hamilton was still very much a deserving champion. Only Alonso’s performance was rated better by the model in 2014.

So how did Mercedes become so dominant? Ecclestone made the claim recently that Mercedes gained an advantage due to an unfair head-start in development, due to knowing some details about the planned V6 engines before the opposition did. However, this advantage can probably have only amounted to a few months, as all the manufacturers were actively involved in the dialog over the new engines. The real answer is that Mercedes prepared more meticulously for a coming regulation change than possibly any team in history.

The current Formula 1 engines are far more complex than any before them. Even for huge entities with experience developing hybrids, such as Honda, the regulations posed a formidable technical challenge that demanded hundreds of staff performing years of research and development to be even remotely competitive. In hindsight, it seems only Mercedes recognized the enormity of the challenge and the importance of succeeding before the development freeze began.

Ironically, Renault were the strongest proponents of a move to hybrid turbo power-units, initially proposing a four-cylinder engine, and even threatening to leave the sport if the technology was not rapidly adopted. However, it was Mercedes who ramped up development very early, spending a rumored €500 million in the course of developing the new power-unit from 2011-2014. The team’s harmonious development of chassis, aerodynamics, and power-unit left Red Bull and Renault looking like strangers who met by coincidence on the first day of winter testing. Ferrari’s initial concept was also surprisingly half-baked given all aspects of development were managed within a single organization, much like Mercedes. The Ferrari 059/3 engine had huge power deficits and appalling driveability. Meanwhile, the only other large-budget team with a Mercedes engine, McLaren, developed such a poor aerodynamic package that they were worse than Williams and sometimes even behind Force India.

Between Mercedes absolutely nailing the new regulations and their competitors completely dropping the ball, the W05 emerged as the most dominant Formula 1 car of its generation.

1. 1961 Ferrari (+8.84 ppr)

The 1961 championship demonstrates what can occur when only one team takes a coming regulation change seriously. The result was probably the largest advantage any engine has had over its competitors in Formula 1 history — even larger than Mercedes’ advantage in 2014. By the model’s reckoning, it was also the most dominant car in Formula 1 history.

In 1958, it was announced that engine capacities would be reduced to Formula 2 levels in 1961. Naturally-aspirated engine capacity would be reduced from 2.5L to 1.5L and compressed engines would be banned. The British manufacturers fought hard against this regulation change, delaying car development until 1960 when it became clear the FIA would not bend. Left with little choice, most Formula 1 teams, including the British manufacturers, ran a modified FPF engine (the Mk. II) from Coventry Climax, which produced around 150hp.

Ferrari’s 1.5L Dino V6 engine was already producing around 160hp in 1958 and this was increased to 180hp by 1961. Playing to their strengths, Ferrari also developed a new 120° V6 engine for the new formula. The new engine produced around 190hp, giving it a staggering 40hp advantage over the competition — the kind of difference one would expect between different categories of racing.

The Ferrari 156 also represented a new design philosophy for the team. After his initial insistence on front-engined cars (“It’s always been the ox that pulls the cart!”), Enzo Ferrari approved the development of a prototype mid-engined design for Formula 2. Following successful tests, this provided the basis for the new Ferrari 156. The distinctive car was nicknamed the “Sharknose” for its dual front air inlets.

With such a huge engine advantage, coupled with a competitive chassis, Ferrari were practically unbeatable, winning the constructors’ championship after only 5 of the season’s 8 races, and taking 5 wins in the 7 races they started (they did not enter the last round, due to the death of von Trips). Who drove the car scarcely mattered. Even the team’s third driver, Richie Ginther, outscored every non-Ferrari driver but Stirling Moss in the 7 races he started. The two upset victories in 1961 both went to Stirling Moss, courtesy of two of his greatest drives. In Monaco, he took an early lead in his underpowered Lotus and narrowly fended off the three Ferraris to victory. In Germany, Moss gambled on wet tyres on a damp but drying track and drove a canny race of tyre management to take the last victory of his Formula 1 career.

The championship was dominated by Ferrari’s top two drivers, Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips. Neither had been a top-level driver before 1961. Hill was a solid performer, but was outscored 27-20 by teammate Brooks in 1960, and 13-1 by teammate Bruce McLaren in 1964. von Trips was also beaten by several teammates, including Phil Hill (in 1958, 1960, and 1961), Hawthorn (in 1958), and Collins (in 1958) during his short career. In the all-time rankings, my model puts Hill 136th, making him the lowest ranked champion in history. von Trips is unranked due to insufficient races in 3 consecutive years (he is ranked 175th based on his 2-year peak). With equal equipment, the model predicts Stirling Moss would be the 1961 champion, with Innes Ireland a close runner-up. As for the Ferrari drivers, von Trips is 12th, Hill is 13th, and Ginther is 17th. Hill’s result is the lowest predicted finish for a champion, equaled by Piquet in 1981 (ranked 13th) and just behind Scheckter in 1979 (ranked 12th).

While the 1961 Ferrari doesn’t top any lists today for dominance metrics, such as percentage wins or pole positions, the model believes it could easily have done so with a top driver line-up and cars present at all the 1961 races.

Predicting dominance

Given a quantitative method for assessing team quality and dominance, it’s tempting to ask what factors lead to a team dominating in Formula 1. Some would see this as a situation that ought to be avoided, since it can make the sport less entertaining for long periods of time.

A large budget is a prerequisite for team success, as my earlier analysis of Formula 1 finances showed. However, money alone does not guarantee the best car. From 1999-2015, the team with the largest estimated budget has produced the model-ranked best car in only 4 out of 17 years.

Team partnerships with dominant engine suppliers have often led to dominance. Examples discussed above include 1952-1953 (Ferrari), 1961 (Ferrari), 1966-1967 (Repco), 1986-1988 (Honda), and 2014-2015 (Mercedes). Great designers also surely contribute to team dominance. Adrian Newey had a hand in 5 of the 20 most dominant cars. However, identifying the specific contributions of certain individuals is verging on impossible now that teams are such large entities. How much of Red Bull’s dominance was down to Newey vs. Prodromou vs. a host of other less famous designers? Without inside knowledge of the team’s operations, and the importance of interactions between certain individuals, that’s an unanswerable question.

Are there certain sporting conditions that make team dominance more likely? What allows a great designer or great engine manufacturer to take a big lead over their competitors? One probable candidate is a change to the sport’s regulations. In addition to resetting the team hierarchy, large rule changes provide the opportunity for one team to discover a much better solution than anyone else. With a static rule set, teams would be expected to become more similar due to convergence to similar solutions and diminishing returns.

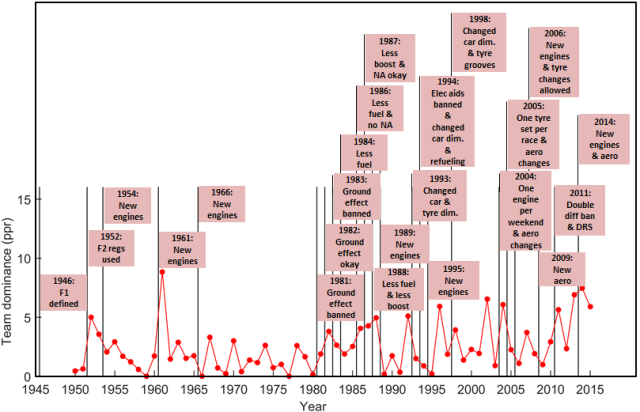

Plotted below is the level of team dominance in each year (the same model metric used for ranking the top 20 teams). Marked on this graph are what I have deemed to be years that involved significant changes to the regulations. The choice is of course arbitrary, but hopefully you largely agree with my choices.

It’s interesting to observe that some of the spikes happen immediately after large rules changes, although there are exceptions. There is a period of relatively low team dominance from 1966-1980 when the rule changes were relatively minor each year. We can also see that 2013-2015 is by far the highest level of average dominance across any 3-year period in the sport’s history.

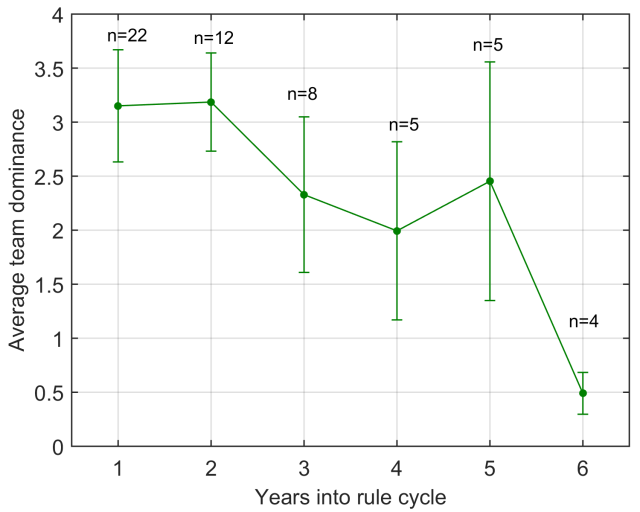

Below is a graph of the average level of team dominance (mean±SEM) versus the number of years into a new rule cycle. The number of years contributing to each data point is marked.

The downward trend is consistent with the idea that team dominance is most likely after a rule change and then tends to decrease while rules are static. So then, is a static rule set a panacea for Formula 1? Not necessarily. A static rule set combined with cost-cutting measures that freeze development, which some would call a necessity in this era, is a recipe for prolonged dominance, as we have seen in 2015. In addition, Formula 1’s chief appeal is the constantly changing technological landscape that forces engineers to solve new and challenging problems. The downside of the rule cycle is dominance, but the upside is the exciting, constantly changing state of the sport. Without that, Formula 1 essentially converges to a dated spec-series. The sport needs occasional change to keep it fresh — the only question is how occasional.

To quote the late, great Denis Jenkinson when he was writing about the proposed 1961 rules changes,

Firstly, the F.I.A. have seen fit to change the Formula, which in itself is no bad thing, for the existing rules will have been in force for seven years by the time 1961 arrives and since Grand Prix racing became organised a change every three or four years has been deemed reasonable, in the interests of preventing stagnation in design. Those people who do not like Indianapolis track racing or Speedway racing bring up the question of design stagnation, pointing out how many years the Offenhauser or J.A.P. engines have been undergoing development and refer to them as archaic. This year’s World Champion Car is the Vanwall and its engine was designed in 1953, so that by the time the new Formula comes into being it will be eight years old. The B.R.M. engine was designed a year later, to be seven years old, and neither engine has made any great change during that time which to me sounds like stagnation of design; or, conversely, steady development work like an Offenhauser or a J.A.P. The six-cylinder Maserati engine started its long period of development as long ago as 1952, and has been unchanged since 1954, and though it is now only the end of 1958, remember that people who do not want a new Formula are suggesting not only that these engines go on until 1961, but that they should be given a new lease of life for a further three years. I say that a change in the Formula is due, and that those who suggest it remains unchanged until 1964 are taking a selfish view.

If Grand Prix racing is to provide progress in the design and development of the racing car then we must have a change, and this new set of rules is a fair challenge to any team of designers, especially as they have two whole years in which to start work. Through the ages Grand Prix racing has been a source of continuous development of the racing car, so I really do not see why we should stagnate now by retaining the already-out-of-date Formula of today for a further three years beyond 1961.

57 years later, not much has changed!

[…] This article previously included a ranking list of the top 20 teams, but the list is now presented here as a companion article for improved […]

Interesting to note: Turbo eras have a higher average dominance than N/A eras.

The FIA could have learned sooner about rule changes affecting dominance – 1952 and 1961 seem to be down to miscommunication in a pre-globalised world.

In the 2017 rules debate, a 1993 type reduction of unexpected dominance is sought. Parallels are drawn with the 1992, 1996 Williams and 2002, 2004 Ferrari leading to wholesale changes.

Throughout Lewis Hamilton’s F1 career, the increasing car dominance effect shows why he joined Mercedes, with a guarantee they would have the best engine.

New aero in 2009 ‘unlocked’ Newey – who’s to say the same won’t happen in 2017? Turbos?

+3.5ppr seems to be a ‘boundary’, at which point dominance will encounter rule changes.

PS. With F1 being defined in 1946, it would be interesting to see something on the ‘lost’ years!

[…] upon a dominant car. There is some evidence backing this. Applied mathematician Dr. Andrew Phillips used a statistical model to rank teams year-by-year on how dominant they were on his blog, F1metrics. Half of Vettel’s […]

Hi, since this is your latest post i decided to post my question here. I would be thrilled to see an analysis of how good Carlos Sainz Jr has proved to be this season. Whether or not it is in your plans to make an analysis where such topic is inquired in some way, is of course, up to you. Thanks for considering and keep up the good work!

Hello. First of all, i’d like to say that your website is a truly great piece of dedication and passion. Well done for this 😉

My question is, can you calculate the Mercedes W06 Hybrid’s score now that the season’s over, and where would it place in the leaderboards?

Thanks for the kind message! At the end of the season, the W06 has now risen to 3rd in the all-time team dominance list. I’ll write a bit more about this in my end of year rankings, which should be out later this week.

Oh, that’s great to hear! Can’t wait to see it posted, keep up the great work!

[…] Although the car was completely dominant — by end of season the W06 has climbed the list of most dominant cars in history from 7th to 3rd — Hamilton saw off the challenge from teammate Rosberg with impressive […]

[…] it would be extremely premature to conclude that the most severe period of dominance in the sport’s history is over, Ferrari’s new contender looks impressive right out of the box. Mercedes will very […]

[…] different in others. In addition to ranking drivers, the models can also be used for ranking the best teams in history. The two most recent models confirm that team performance is a larger contributor than driver […]

[…] performing, and see how the new rules have changed the team hierarchy, if at all. As I showed in a previous analysis of team dominance, major rule changes have a tendency to give a large advantage to one team, whereas static rules […]

[…] Hamilton was helped by driving extraordinarily dominant cars in those years, but we can gain additional insights by examining his teammate head-to-head records in wet vs. dry […]

[…] there was a renewed threat from Ferrari, who switched focus back from sportscars to F1 and had arguably the season’s best car. Meanwhile, Rindt delivered what is rated by the model as one of the all-time best season […]

Would be great if you could update this graph with the other Mercedes cars, now we are three years further, especially the interesting ‘predicting dominance’ part too – does the Mercedes (and Red Bull, even if they aren’t the dominating car any more, in terms of end-of-season-aero they might still close, though I don’t know whether that features in the graph.).

In his article “Drivers championship won in off-pace cars” Patrick O’Brien calculated that the fastest car in 1982 was not Ferrari, but Renault RE30B.

For 1986 he stated Ligier-Renault JS27 was equal to Williams.

And for 2004 Schumacher’s brilliance obscured the fact that BAR-Honda 006 was the fastest car.

Each analysis seem to lack something some other analysis has and which tends to change the picture, seeing it often can’t be refuted and it’s irresponsible to discard it. I yearn for a world where multiple authors would discuss the validity and importance of each element that goes into creating these models.

While I find O’Brien’s work interesting, it’s not an objective model. The way that model works is that the author subjectively decides who were the quickest drivers in each year (the best performers). Differences between drivers and teams are then deduced via comparisons.

[…] the equation (i.e., imagining what would happen if all drivers had equally competitive cats), and ranking the most dominant F1 teams in history by taking the Driver effect out of the equation (i.e., imagining what would happen if all teams […]

[…] he would have raced the Ferrari 156. I have performed analysis of this car before, concluding that it was likely the most dominant car in F1 history in terms of performance. This car had about 25% more horsepower than the best […]