Welcome to the fourth part of this five-part series, in which I apply the f1metrics model of driver and team performance to simulating historical hypothetical situations. This time, it’s a French edition, covering three famous French drivers who didn’t get to deliver their full potential in F1.

If you want to check out the previous articles in this series, they are linked here:

Part II (Kubica, Clark, Donohue, Revson)

Part III (Bellof and ex-champion comebacks)

Method

For each hypothetical scenario below, I simulated either the extension/comeback of a driver’s career or a change in teams during their career. Two types of outcomes are presented for the simulated scenarios:

(i) The adjusted driver performance rankings (in ppr) for each season, including the driver’s predicted hypothetical performance at that age and with that level of experience. This is a ranking (ranging 0-10) of absolute driver performances, taking teams out of the equation. In other words, it’s how the model predicts the drivers of that season would have performed in equal machinery. This is the same approach I use for my end of season driver rankings each year.

(ii) The predicted World Drivers’ Championship standings for each season. In cases where these tables are presented, I am including the effects of a driver’s hypothetical team on their points scored. In this simulation, I have used the team’s average reliability that season to generate the number of mechanical DNFs. To generate point tallies, I mapped the model’s scoring rate function to all other points scoring systems in F1 history so that I could convert between ppr and points scored.

What if Jean Alesi had raced for Williams?

Jean Alesi’s career never delivered on its early promise. Few can forget Alesi’s duel in the streets of Phoenix against Ayrton Senna in only his ninth grand prix. Virtually anyone watching the sport who was surveyed at that point in time would have said this is a driver destined for many wins if not greater achievements. Yet, Alesi finished his career with just 1 win from 202 starts. As a result, he has become one of the sport’s most frequently discussed what-ifs. Was Alesi not as good as his early reputation suggested, or did he just miss his chances?

The major branch point in Alesi’s F1 career occurred in 1990. After a very exciting couple of seasons with Tyrrell, Alesi was a hot commodity on the driver market. A situation arose in which he had reportedly signed contracts with three teams simultaneously: Tyrrell, Ferrari, and Williams. Alesi ultimately honored the Ferrari contract, which in retrospect was a dismal decision. In 1991 he was paired with the formidable Alain Prost. Neither driver managed to win a race, and Prost convincingly outperformed Alesi, lowering Alesi’s perceived value in short order. From there, Ferrari went into a further nose-dive, with 1992-1993 being one of their least competitive periods in F1 history.

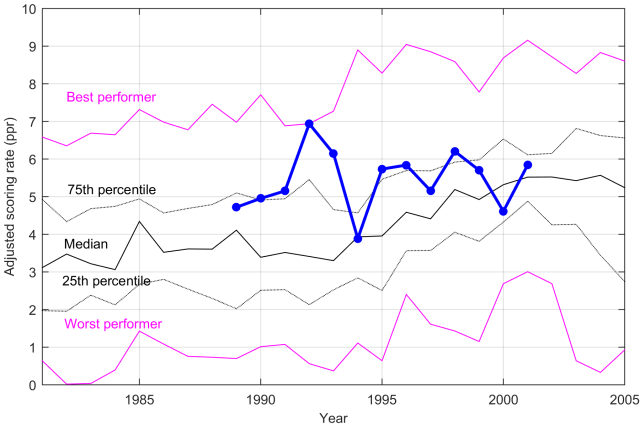

Below, we can see Alesi’s driver performance rankings plotted across his career.

In his first two years at Tyrrell (1989-1990), Alesi was already performing well above the average driver. His 1992 season performance is actually ranked the best of any driver that year, as he scored 18 of Ferrari’s 21 points in a very difficult year for the Scuderia. It was Ferrari’s least competitive car since 1981, while Williams — the team Alesi rejected — romped to both titles.

In his first two years at Tyrrell (1989-1990), Alesi was already performing well above the average driver. His 1992 season performance is actually ranked the best of any driver that year, as he scored 18 of Ferrari’s 21 points in a very difficult year for the Scuderia. It was Ferrari’s least competitive car since 1981, while Williams — the team Alesi rejected — romped to both titles.

What if, instead of following his heart, Alesi had followed his head and chosen Williams? They were on the ascendancy in 1991, and the probable driver line-up of Alesi and Mansell would have been absolutely spectacular to watch. We can imagine Alesi swapping seats with Riccardo Patrese in 1991 and 1992, and then swapping seats with Damon Hill in 1993 and 1994.

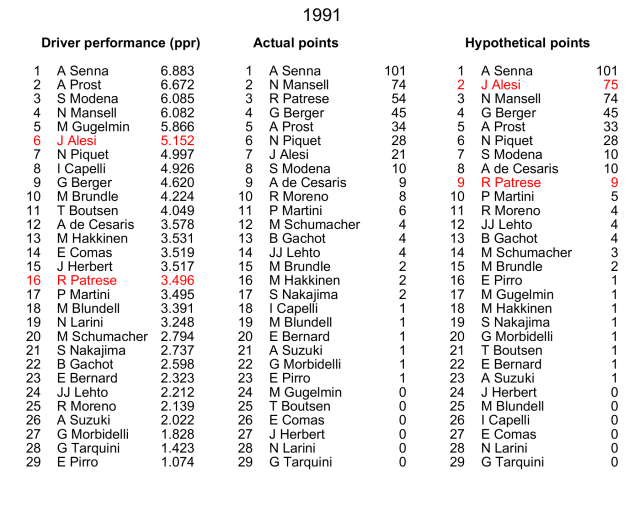

Examining 1991, the model predicts that Alesi would have performed considerably better than Patrese in the Williams seat, while Patrese is predicted to score only 9 points for Ferrari. In fact, Alesi could have narrowly outscored Mansell due to Mansell’s 4 mechanical failures and 1 DSQ.

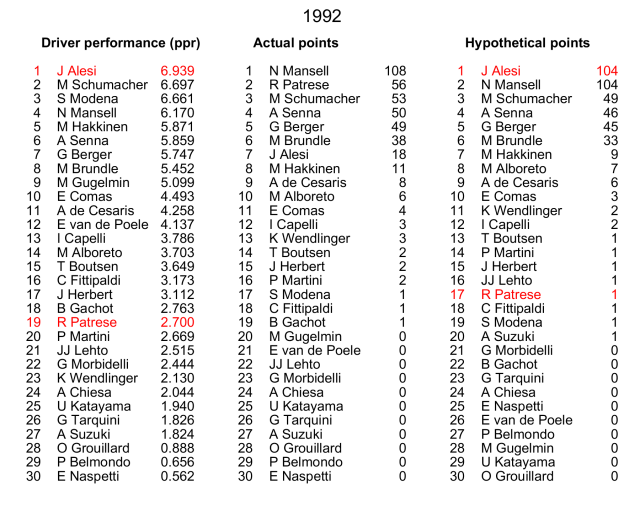

Had Alesi driven for Williams in 1992, he would have had an incredibly dominant car at his disposal.

Had Alesi driven for Williams in 1992, he would have had an incredibly dominant car at his disposal.

Am imagining of Alesi driving for Williams in 1992. Credit to the original article here: https://www.motorpasion.com/formula1/jean-alesi-y-la-decision-con-cabeza-en-lugar-de-corazon

As noted above, Alesi is narrowly rated the best performing driver in 1992. Coupled with the dominant Williams FW14B, Alesi is the predicted champion. However, he wins by the smallest possible margin — the reason being that Patrese’s car suffered worse reliability than Mansell’s in 1992 (3 vs. 2 mechanical DNFs).

Naturally, this is assuming Alesi wouldn’t fall for the same misleading information that Mansell supplied Patrese in 1992. The older and cannier Mansell might well have won that season versus the frequently temperamental Alesi on mindgames alone.

Naturally, this is assuming Alesi wouldn’t fall for the same misleading information that Mansell supplied Patrese in 1992. The older and cannier Mansell might well have won that season versus the frequently temperamental Alesi on mindgames alone.

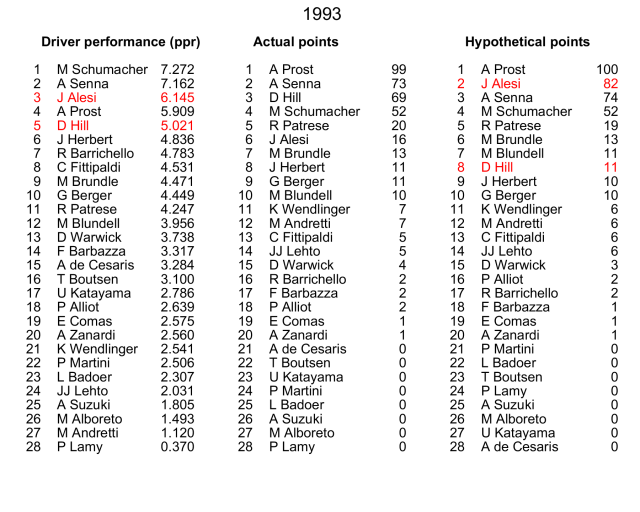

Had Alesi continued with Williams into 1993, he may have been paired with Alain Prost, just as he was historically in 1991. Alesi was now at his peak, whereas Prost was 38, returning from a 1-year sabbatical. Prost didn’t deliver his strongest performance that season, according to the model.

With these factors in his favor, the model rates Alesi a close match for Prost. Based on his performance, the model sees Alesi as a better-performing driver than Damon Hill in 1993 and likely to give Prost a close fight for the title. Whereas Hill is predicted to score just 11 points for Ferrari.

Williams had a dominant car in 1993, but it was not bulletproof. Like 1992, this is a championship outcome that is likely determined by reliability. Prost had far the better run of reliability at Williams that season (1 mechanical DNF vs. 4 mechanical DNFs on Hill’s car).

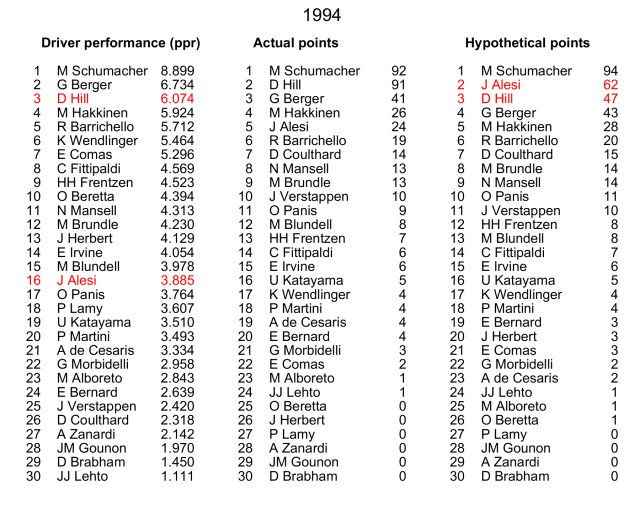

In 1994, Alesi’s performance is rated considerably weaker than in 1993, as he was historically beaten comfortably by his Ferrari teammate Gerhard Berger. A seat swap between Alesi and Hill this time is bad for Williams, good for Ferrari. Alesi is predicted to finish a distant 2nd in the championship, with Schumacher given an easy path to his first title.

In 1994, Alesi’s performance is rated considerably weaker than in 1993, as he was historically beaten comfortably by his Ferrari teammate Gerhard Berger. A seat swap between Alesi and Hill this time is bad for Williams, good for Ferrari. Alesi is predicted to finish a distant 2nd in the championship, with Schumacher given an easy path to his first title.

This hypothetical clearly demonstrates how one or two bad team decisions can completely shape a driver’s career metrics of success. In his actual career, Alesi never finished better than 4th in the championship and won just one race. In the above hypothetical, he would compete for two titles, potentially winning one, and likely winning at least 15 races, putting him among the top 20 most successful drivers in F1 history. I think many would consider this a more fitting legacy for Alesi.

This hypothetical clearly demonstrates how one or two bad team decisions can completely shape a driver’s career metrics of success. In his actual career, Alesi never finished better than 4th in the championship and won just one race. In the above hypothetical, he would compete for two titles, potentially winning one, and likely winning at least 15 races, putting him among the top 20 most successful drivers in F1 history. I think many would consider this a more fitting legacy for Alesi.

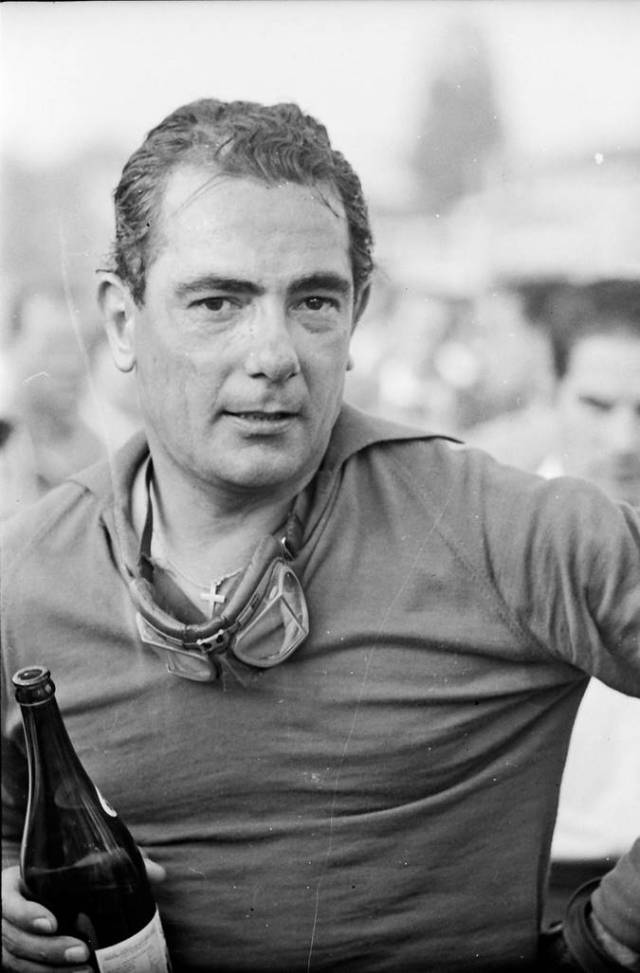

Jean Behra

Dig into the what-if literature in F1 and you will invariably come across the name Jean Behra. He could be considered a sort of Stefan Bellof of the 1950s. A more obscure, but highly enduring, cult hero. Behra won the hearts of fans with his stylish and daring driving, compared later to Gilles Villeneuve. He was rated #38 in a list of all-time greatest drivers in a poll of motorsports experts, where he was described as having the talent to win titles, although he never actually won an F1 championship race.

Remarkable stories about Behra are easy to find. His debut in a championship F1 race occurred in secret. He took the place of Maurice Trintignant, who was ill that weekend, even donning Trintignant’s helmet to remain disguised.

A month before his death, Behra punched the Ferrari team manager and a restaurant patron after an argument following an engine failure in the race. It was reportedly suggested that Behra had overreved the engine. Followed the incident, Behra was immediately sacked from the team.

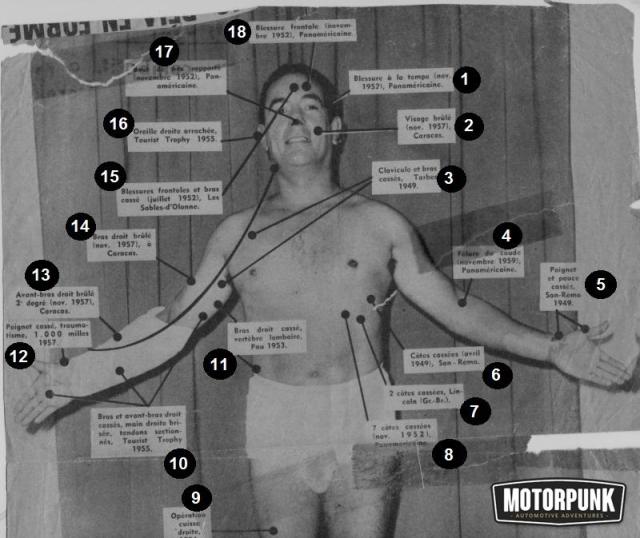

Behra survived numerous serious crashes in his career, resulting in serious injury, as shown in this newspaper graphic below, and described in detail here. This included an accident in 1955 that sliced off his ear, resulting in him wearing a prosthetic ear thereafter. Despite this reputation, his crash rate in championship F1 races was quite low. In 53 starts, he had only two races that ended in a crash.

As far as career hypotheticals go, there is not too much to be said for extending Behra’s career in terms of peak performance. At the time he unfortunately died (in a massive crash off the banking at AVUS), he was already 38 years old and very experienced. We already saw his best potential years during his time in F1 from 1952-1959.

We could, however, ask what Behra might have achieved in more competitive machinery. The fact that Behra never won a championship F1 race was rather unjust, given the number of non-championship races he won, and the fact that he finished 5 times on the podium in 7 races in 1956. It is commonly argued that had Behra been in one of the top teams, he would not only have won races but potentially titles.

Using the f1metrics model, we can ask how Behra’s performances measured up against his contemporaries. I will use this case to give a preview of outputs from the newly upgraded f1metrics model, which I’m currently using to prepare an updated all-time driver ranking list.

A summary of Jean Behra’s career. The top plot shows his estimated driver performance in each season, including his season rankings. The bottom plot shows his teammates with whom he started at least 5 races in equal equipment (same team, same customer/non-customer status). Line width represents number of starts together. Line color represents who had the stronger estimated driver performance based on points per counting race (red means Behra was worse; green means Behra was better).

From the above graph, we can see that the model consistently ranks Behra just inside the top 6 drivers on the grid during his career, comparable to drivers such as Peter Collins and compatriot Maurice Trintignant. Given that Collins and Trintignant won 5 races between them, it’s fair to say that Behra could and should been a race winner given more time in competitive machinery or a bit better luck.

As teammates, Behra had a very respectable record against Stirling Moss: 3-3 in counting races, 3-5 in qualifying, and 28-29 in points. Against the great Juan Manuel Fangio, the tally was more one-sided: 0-4 in counting races, 1-5 in qualifying, and 6-37 in points.

So could Behra have ever been champion? I can see only one seriously plausible scenario for this. Had Behra not immediately destroyed his relationship with Ferrari in 1959 and stayed there into 1961, he would have raced the Ferrari 156. I have performed analysis of this car before, concluding that it was likely the most dominant car in F1 history in terms of performance. This car had about 25% more horsepower than the best competition.

Phil Hill at the wheel of the massively dominant Ferrari 156 in 1961.

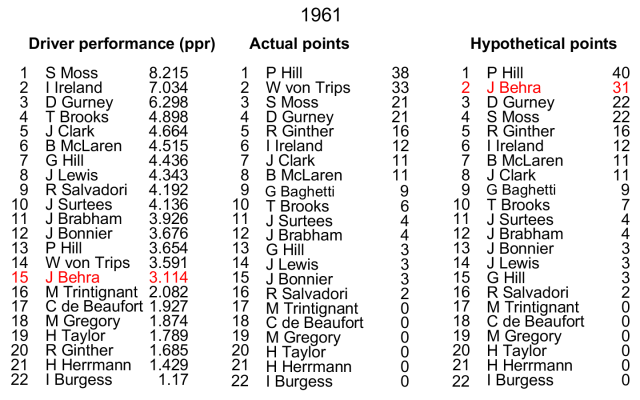

By 1961, Behra would have been 40, up against the younger Wolfgang von Trips (33) and Phil Hill (34). However, Behra had more talent on his side than those two drivers, meaning it could have been a close-run championship. We can see the model’s predictions below.

None of the Ferrari drivers are rated highly in terms of their performance that year. The model puts Phil Hill at #13, Wolfgang von Trips at #14, and Jean Behra at #15. Had they been in equal equipment to Stirling Moss, none of those drivers would have had a fighting chance. But such was the dominance of the Ferrari in 1961 that it almost didn’t matter. In a hypothetical history with Jean Behra replacing Wolfgang von Trips, the model gives Phil Hill a slight edge over Behra in the championship, but small enough that the 8-round championship could have been swung by a single bad race.

At the very least, Behra would surely have finally taken some race wins.

Francois Cevert

Francois Cevert is considered one of the great lost talents of the 1970s. Taken under Jackie Stewart’s wing while still a Tyrrell junior driver, Cevert benefited from the tutelage of one of the all-time greats. In Stewart’s own words, “I told him everything I ever knew.”

After racing at Tyrrell as Jackie Stewart’s teammate for four years, Cevert was set to take a leading role at the team as Stewart planned to retire at the end of 1973. Tragically, Cevert died in a horrific accident during qualifying for the final race of 1973. Stewart withdrew from the race, retiring on the spot.

Had Cevert survived, could he have challenged for titles? In Jackie Stewart’s own words,

“I think I brought him from what might have been considered to be just another driver into somebody who I think would have gone on to win the world championship, of which, I would have been very proud.”

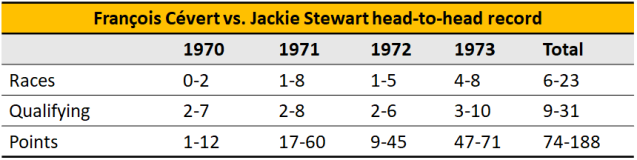

To understand Cevert’s potential, we need to examine his head-to-head record against Stewart.

Overall, it was an incredibly one-sided battle. Cevert’s record of beating Stewart in 21% of counting races (6/29) is comparable to Eddie Irvine’s record of 20% (7/42) against Michael Schumacher, or Giancarlo Fisichella’s record of 19% (5/31) against Fernando Alonso.

However, Stewart had a significant advantage in terms of experience, at least in their early seasons together, as Cevert was a rookie in 1970. Looking across the years, we can observe some progress in Cevert’s performances. Even in 1973, he was far from performing at Stewart’s level, but his record was far more respectable. Indeed, the model ranks Cevert #5 in the championship that year.

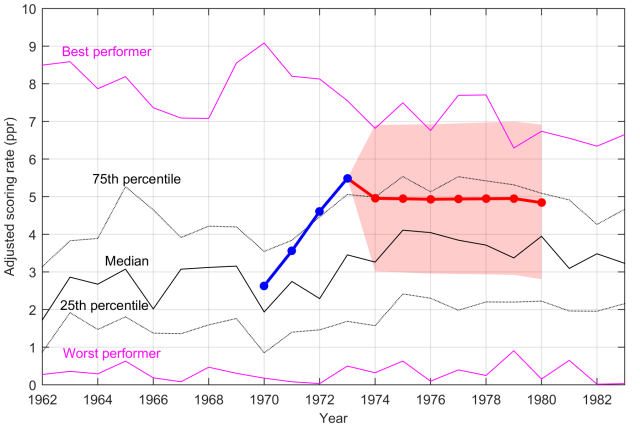

Another metric we can use to gain insight into Cevert’s performance is his qualifying gap to Stewart. This is shown on a per-race and per-season basis is the graph below.

Francois Cevert’s percentage differences to Jackie Stewart in each qualifying session. Dashed lines and values showed the median difference for each season that they were teammates.

Overall, the median gap between them was large: 0.95% of lap-time. Some fraction of this may have been attributable to Stewart’s perks as the number 1 driver. We can also see that the gap appreciably came down over time, sitting at a median gap of 0.34% in their final season together. This is still a sizeable gap in F1 terms, but evidence that Cevert had improved to touching distance.

If we project Cevert’s performances into the future, the model does not predict further improvement for Cevert. At age 29 and with four years of F1 experience, Cevert was already near peak performance. Cevert’s improvement from 1972 to 1973 is substantially bigger than would be predicted based on an incremental gain of experience, suggesting that he was also in relatively strong form in 1973. Cevert’s predicted average performance in 1974 and beyond is therefore a tad lower than his observed performance in 1973. However, note the bounds of uncertainty — in the best case scenario, he may have been among the season’s best-performing drivers in some future seasons.

For the sake of a hypothetical, we can reasonably assume that Cevert would have continued into the planned number 1 role at Tyrrell in 1974. I assume he would be racing in place of Jody Scheckter, alongside fellow Frenchman and previous Tyrrell driver, Patrick Depailler.

Scheckter put it in a superb performance in 1974 to almost challenge for the championship. In fact, the model rates this the best season performance of Scheckter’s career. While such a performance is within the uncertainty bounds of Cevert’s predicted performance, Cevert’s average predicted performance is lower than Scheckter’s in 1974. The model therefore sees Cevert as a likely race winner but not title contender in 1974.

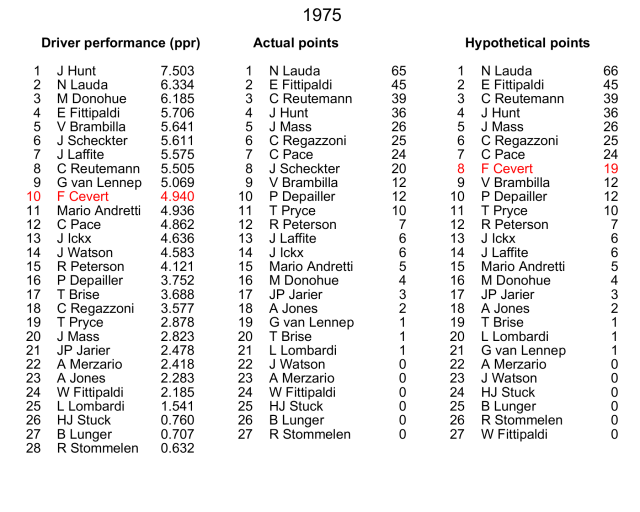

In 1975, Tyrrell took a major step backwards, falling to 5th in the constructors’ championship. Assuming he was still with the team, Cevert is predicted to score 19 points, similar to the 20 points that Scheckter actually scored.

In 1975, Tyrrell took a major step backwards, falling to 5th in the constructors’ championship. Assuming he was still with the team, Cevert is predicted to score 19 points, similar to the 20 points that Scheckter actually scored.

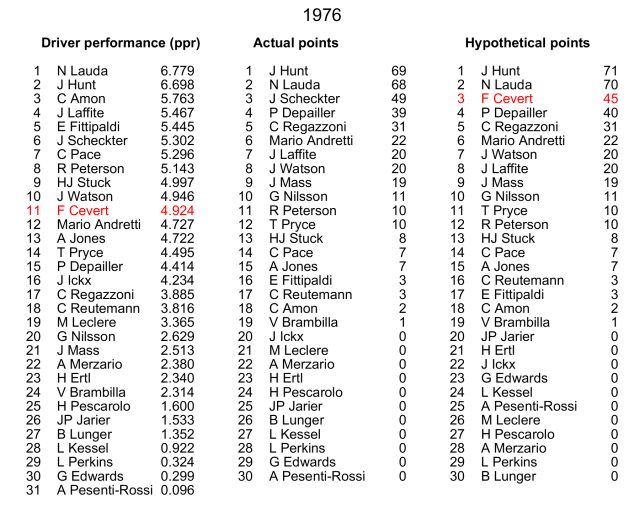

Tyrrell rebounded in 1976 with the clever 6-wheeled P34, finishing top 3 in the constructors’ championship, the last time the team would ever achieve this.

Jody Scheckter driving the successful 6-wheeled Tyrrell P34 in 1976.

The model rates Cevert’s predicted performance similar to Scheckter’s in 1976, meaning he would likely have finished a distant 3rd in the championship, trailing the Hunt-Lauda battle.

In summary, Cevert would likely have been among the stronger drivers on the grid through the mid-1970s. Had he remained at Tyrrell he would have built significantly upon his single win, but it is unlikely that he would have won a title.

Keep ’em coming!

“Few can forget Alesi’s duel in the streets of Phoenix against Ayrton Senna in only his ninth grand prix.”

-Like it happened with many drivers before and after, people forgot about the specifics of that situation and the hidden strength of his car and attributed it all to the driver.

“Neither driver managed to win a race, and Prost convincingly outperformed Alesi, lowering Alesi’s perceived value in short order.”

-Having recently watched the 1991 season I was surprised how far this is from the truth.

It seems Alesi was much more competitive than what I’ve heard before. The end result was largely due to Prost finishing his best races and having issues at lesser important once, while the opposite was true for Alesi. It’s also difficult to imagine those two were on equal footing in the team. It seems Alesi was either aware he’s #2 or he had entirely way too much respect for Prost, unlike Leclerc has for Vettel now.

Realistically, Prost was always going to beat Alesi, but in an ideal scenario that duel would’ve be a hell of a lot closer.

Other than that it’s strange to look at car #2 retirement rate when recalculating the season results. It would’ve been more realistic to use average number of mechanical retirements for both cars.

PPR’s volatile nature “shines” through again with Alesi being best performer in 1992 and close to 25th percentile in 2000. Both of those are unlikely.

I’ll note the strangely high rating of Gugelmin and Capelli probably due to underrating their car, as well as the fact that Gugelmin was nowhere on pace in that season and Capelli’s DNF’s have probably pushed him below in rating. In most situations where fighting for points is more important than just having as many finishes in a superior car Capelli would’ve been rated far higher.

I have no idea what poor Schumacher had done to be ranked #20, behind Larini, in a rookie season where he seemed to be at least equal to Piquet, if not better already.

A lot of other rankings also read weird, both on the account of chosen metric and the fact that your hypothetical results insert the changes in the season as-it-happened instead of attempting to recalculate the season as-it-is-most-likely-to-have-happened if it was run many times and the average result obtained.

Behra’s case is as interesting as any, but does he really have enough fans to warrant such an exploration? I guess it’s in line with the french theme, though.

Finally, I never understood why Stewart or anyone thought Cevert would end up anything more than a good, but not exceptional driver. Whatever he saw in him, doesn’t show in his results.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply. I’ll just note that this is still using the older f1metrics model — with age and experience effects, but without robust scoring. Some of the season driver rankings you note that are down to outlier results have ironed out now with the robust scoring of the new model. This will be clear in the updated all-time rankings.

You’ve argued that every model has to pass a basic sanity check and not have Katayama ranked ahead of Mansell yet it’s more likely Katayama was better than Mansell than any scenario in which Schumacher and Nakajima would be closely matched teammates.

Robust scoring will help by virtue of being closer to the sweet spot but fewer samples in seasonal ratings really highlight the issues of simplistic treatment of driver DNF’s.

As a result Patrick O’Brien’s driver speed ratings for 1991 seem to offer a couple less wtf’s than this model’s interpretation, despite completely ignoring DNF’s.

Schumacher vs Piquet race positions graph:

https://imgur.com/a/Qfp639Q

Robustness at a per-season level is never going to be as high in any model as robustness at a per-career level, so I’m unsure why you compare the two (Schumacher vs. Nakajima’s rating in a single season; Mansell vs. Katayama’s rating across their entire career). Schumacher’s 1991 rating is based on a total of 4 counting races, so I would consider it as good as garbage as far as interpretation goes. In any case, robust scoring does put him a little ahead of Nakajima that season, but I think it simply a moot point.

O’Brien’s rating system is based entirely on subjective assignments of who was the fastest driver in each season. While it’s an interesting system, it isn’t objective and therefore doesn’t provide the same advantages as an objective model. I wouldn’t be surprised if subjective ratings tend to generally align with majority subjective opinions, since they are directly influenced by them.

@Robustness at a per-season level…

I’m not sure there is need for apologetic arguments. Potential space for improvement or a perceived weakness would not disqualify the entirety of your effort, or even harm it.

Feel free to constrict the Mansell vs Katayama example to Katayama beating him in a single season. That would be enough to move the theory from absurd to possible. Ranking Ricciardo over Vettel, for example, would certainly pass a sanity check.

It’s strange to consider Schumacher’s rating based on a total of 4 counting races as good as garbage since with the amount of non-driver DNF’s in 1991 a decent matchup would probably consist of 8 or so races.

Even with a model that is great on a per-career level, seasonal driver performance in that case could be considered a half point between “great” and “as good as garbage” and there’s no need for that.

Obviously robustness increases with sample size, but even a single race can be either very representative of season performance or not at all.

The model’s chosen output might not be conducive to seasonal rankings or Schumacher’s sample might not be representative due to rare circumstances.

It doesn’t feel like the latter is the case. The model might simply be disregarding the effort in races with mechanical DNF’s and punishing driver DNF’s beyond their actual scope (not losing 1, 2 or even 0 points by retiring but being ranked as the worst driver in that race, maybe even more so in case of having a more competitive car), or simply averaging the whole thing and treating a driver that DNF’s in 1/2 races as likely to crash out of 11 races in 2020. That would practically make it a DNF counter on a per-season level. No actual changes to the model would be needed to correct for this, just an adjustment in presentation to accommodate a smaller sample.

Example:

Let’s treat finishing position as a precise measure of performance, which is something I think your model already does.

Piquet: 6 5 11 7 4

Schumacher: 5 6 6 R R (only one retirement being a counting race with 0 points)

Piquet’s non-adjusted ppr using 10-6-4-3-2-1 system ends up 1.34 and Schumacher’s 1.00, a big difference. But Piquet isn’t actually expected to have a 0% driver DNF rate nor is Schumacher expected to have a 25% driver DNF rate.

In this scenario any imperfect solution would sacrifice less than the current one does. How about a career average driver error rate for seasonal calculations? Or how about this to account for drivers changing their aggressive styles, a play on peak performance – period crashiness rating™. A driver DNF % for each season as an average # of driver DNF’s in all races that season and seasons directly before/after, with the exception of drivers at career start/end/insufficient races.

Let’s see how that would work:

Piquet’s ppr stays the same at 1.34. Schumacher’s ppr now rises to 1.33.

From 1991-1993 Schumacher had cca. 5 driver DNF’s in 38 races, period crashiness rating™ of 0.132. From 1989-1991 Piquet had cca. 6 driver DNF’s in 48 races, period crashiness rating™ of 0.125. Now we can apply the estimated ratio of lost points due to self-harm to their ppr’s and get a final result of

Piquet 1.17 ppr

Schumacher 1.16 ppr

The remaining “inaccuracy” (depending how you look at it) now lies in the fact that team and opposition performance might not be the same in races where one driver had a DNF. (let’s leave the likelihood of DNF’s in wet races out of this for now)

In the three races they both finished Piquet had a ppr of 1.03 and Schumacher 1.33. After applying the period crashiness rating™ it comes down to

Piquet 0.90 ppr

Schumacher 1.16 ppr

Last two results coincide well with my impressions of watching the season summed up in a previously mentioned comment.

@O’Brien’s rating system is based entirely on subjective assignments…

I see what you did there. O’Brien’s system is based on laptimes and teammate/car performance.

The subjective part comes in the form of selecting the fastest driver of the season, but in case of 1991 both your model and O’Brien chose Ayrton Senna, although that’s not to say his is automatically on par with your model, even if they were measuring the same thing.

Equally, I would not dare to criticize the model on the account of rankings not matching driver reputation. Was Pedro Chaves a lost generational talent? It doesn’t seem that way, but what the hell would I know about that.

Just note that in the 1991 case, the model calculates points per race on a per-season basis, meaning Piquet’s ppr is calcuated using all counting races for the team, not just the subset he started with Schumacher alongside him. Of course, a team’s competitiveness can vary within a season, so this is not always a 100% fair comparison, but it is generally fair and allows for more robust comparisons in most cases.

Noted. How much that choice changes career rankings overall probably has a lot to do with the specific mechanics of each model but I’m not sure excluding such subsets contributes much beyond a simpler approach. They’re objective and their low confidence level doesn’t have the same damage potential as Piquet perhaps undeservedly besting Schumacher would. (I imagine drivers changing/joining teams mid-season likely suffer some performance penalty as well)

In any case a subset ppr (or even a combination of subsets) might look better when presented in seasonal rankings.

I wonder is it also the case that per-race performance variability was greater in older seasons. Eric van de Poele is a particularly curious case, although that whole season is full of strange results by today’s standards.

I completely agree with you on most of your points. I was also watching the 1991 review and some select races and some PPRs do seem abnormal. Race “weight” (or value) was rather important in the past (prior to 2010s or even 2000s). As you said, season averages might produce different results, especially if things like DNFs (luck) and/or psychological war (as it was stated in Alesi vs Mansell) was taken into account. That would be even more interesting to see.

Looking forward to Part 5 and the revisited all time list!

Hey, great work as always, and good to see a teaser of the new model.

One minor ask: as someone who’s colour blind, is there any chance of using a non-red/green colour for the spoke graph of comparative team-mates? I literally can’t tell them apart lol

Thanks for the suggestion, I’ll make that change for the all-time rankings graphics!

Thanks!

An interesting article but, as an aside, I feel it is one where you have erred with the narrative over Alesi and his contract negotiations for 1991.

A number of people have repeated the story that Alesi made a decision “with his heart rather than his head” to race for Ferrari in 1991, but the story from Alesi’s side is rather different and suggests Williams weren’t serious in their negotiations with Alesi.

In early 1990, Williams approached Alesi and promised that, if he did not sign a contract with another team before September, they would consider beginning negotiations with him over a possible three year contract deal in September.

It’s important to note that Williams were not offering Alesi a contract at that point in time – all they offered was the promise that they might talk about a contract. Alesi was indeed aware of how Williams’s form had been improving in recent years, so he agreed to sign something which was closer to a memorandum of understanding – not a contract, rather something closer to a formal expression of interest instead.

Now, Williams had originally promised they would make an announcement about the drivers they were negotiating with at the French Grand Prix, but that came and went. By that point in time, Alesi was starting to get frustrated with the lack of information from Williams and then went to Ferrari to see about a back-up plan – and, unlike Williams, Ferrari showed much stronger interest in Alesi and did make a formal contract offer to him.

Alesi has indicated that Frank Williams was just stonewalling him every time he tried to discuss the possibility of a contract with Williams – it was that lack of interest that resulted in Alesi going to Ferrari, as he saw it as both a back-up option and the only way he might be able to put some pressure on Williams to act.

When it came down to it, Alesi chose to sign for Ferrari because Ferrari was the only one that was actually offering him a contract – Williams never put together a formal contract offer to Alesi in the end, and the impression he got from Williams is that they were not going to make a formal offer.

Instead, he felt that Williams were just using the threat of signing him in an attempt to make Nigel Mansell lower his demands, as Mansell was the driver they really wanted to sign. In that sense, Alesi’s decision actually makes perfect sense – he signed with the best team that was actually prepared to make a formal contract offer to him.

Thank you for that insight! That definitely goes against the classic narrative, but would better explain Alesi’s decision making.

Spookily timed, but Motorsport.com just published a video on this very topic:

https://www.motorsport.com/f1/video/the-mystery-of-jean-alesis-williams-f1-contract/454302/

[…] Part IV (Alesi, Behra, Cevert) […]

Great work as always! How does the model predict that Ronnie Peterson would have performed if he had raced for McLaren from 1979 to, say, 1983 instead of John Watson?

[…] are each stories of unfulfilled potential. Jean Alesi, who could in different circumstances have challenged for titles at Williams. Stefano Modena, who was brilliantly quick, but highly temperamental. And Mika Salo, who only got […]

[…] Historical hypotheticals: Part IV […]