Who was the greatest F1 driver of all time? It is an endlessly debated question amongst fans and pundits alike. If the only aspect we care about is the number of titles or grand prix wins, then the answer is straightforward. Yet, as F1 fans, we recognize that the question is far more complicated.

F1 is a team sport. As far as team performance goes, the driver is a relatively small contributor. To put it another way, F1 is not a level playing ground for drivers. Some of the most talented drivers in the sport’s history won no titles, simply because they never raced in a sufficiently competitive car. If our objective is to rate driver performances, then we need to somehow make allowances or corrections for a driver’s car competitiveness. Most subjective ranking lists already do this to some degree. Witness the fact that Stirling Moss (no world titles) is often placed near the top of such lists. However, subjective rankings are prone to bias and dependent on each individual’s subjective mental model, shaped by the races they have or have not seen or analyzed.

An alternative approach to driver rankings has developed over the past several years. This approach is to use an objective statistical model to attempt to separate driver performance from car performance and other key factors. One advantage of such an approach is that the results, and how they depend on the model itself, can be directly scrutinized. Another advantage is that models can be used to identify and challenge subjective narratives that do not really have any basis in fact.

Five years ago, I used such a model to generate a top 60 all-time ranking list, which remains the second most viewed article on this blog, behind only my post explaining the rules of racing. The model I used at that time was fairly simplistic, accounting for only driver performance, team performance, and competition with other drivers in the same season. There were fairly obvious steps available to improving the model, including the incorporation of age and experience effects, although the implementation was not altogether straigtforward. Having made a series of upgrades to the model over the past 5 years, I feel it is time for a major update to the all-time rankings. This time, it is a top 100.

I know this has been a highly anticipated and requested post. I hope I have done it justice.

THE MODEL

The statistical model used for generating driver rankings has been described in some detail in a recent post, where I documented the latest upgrades.

To briefly summarize, the outcome that the model attempts to predict is a driver’s scoring rate in each season (points per race, or ppr for short) in their counting races. A counting race is defined as any race in which a driver did not experience a non-driver DNF (e.g., a mechanical DNF or a DSQ on mechanical grounds). Counting races include races where a driver finished, as well as races where a driver had a DNF for other reasons (e.g., they crashed, they gave up, or they had a DSQ on driver-conduct grounds).

To allow comparisons across eras, a uniform scoring system is applied, which has a similar shape to the current 25-18-15-12-10-… system, but extends (exponentially decaying) beyond 10th place to allow performance differences between lower performing cars to be easily discriminated. The scoring rate outcome variable is linked to the model’s performance variable via an S-shaped (sigmoidal) function. This is necessary because there are maximum and minimum possible scoring rates, so a linear model would not suffice.

Schematic representation of the updated f1metrics model. The performance model is a function of several predictors: Driver performance, Team performance, Customer car status (1950-1980), Season, Driver Age, and Driver Experience. Performance is converted to scoring rate in points per counting race (ppr) on a standardized scale of 0-10 using a sigmoid function. The model parameters are fit to data from 1950-2019. Only ‘counting races’ (i.e., excluding non-driver DNFs, such as mechanical DNFs) contribute to the calculated season scoring rate for each driver.

A number of predictors go into the model. First, a performance level specific to the individual driver. Second, a team performance level specific to the chassis-engine-year combination. Third, a factor that represents the effect on performance of having a customer car (relevant pre-1980 when customer cars were allowed). Fourth, a season specific factor, representing the relative difficulty of scoring in a given season. And finally, driver-specific age and experience effects.

Each of these factors in the model are fitted by applying the model to all of the race result data from 1950-2019. As I had to choose a cut-off point for running the model to write this post, I chose Japan 2019. I will continue annually updating the ratings as they evolve in future posts.

Experience-related performance effects are found to be most pronounced in a driver’s first two seasons, leveling out quickly from there. Age-related performance effects are found to mostly affect drivers below the age of 25 and after the age of 35, steeply declining after age 38.

The model’s experience and age effects on performance, derived by fitting the model against all race result data from 1950-2019.

As with any model, it is important to be aware of the underlying assumptions so that the results can be appropriately interpreted. I will note a couple of key properties. First, there is no attempt in the model to attribute blame in collisions. Second, there is no attempt to correct or adjust for results where a driver’s race was affected by mechanical issues (e.g., a long pit-stop or a damaged floor). Handling either case would require subjective judgments, and furthermore would not be possible in many historical cases where we lack footage or even descriptions of many incidents.

With this model in hand, there are many potential applications. One thing we can do is determine each driver’s performance level in each season after adjusting for their team performance. In other words, how might a driver have performed if their machinery had been equally competitive to all other drivers in the same season? And furthermore, if we also adjust for season, what are the relative levels of performance of drivers between eras? These calculations are the basis for the driver rankings presented below.

TOP DRIVERS BY ERA

Before we get to the top 100, I think it is very informative to look at top driver performances within eras. While the f1metrics model is constructed to be able to compare performances across eras, via the chain of teammate links that span 1950-2019, we need to remember that the model is comparing abilities in a relative sense. It can’t directly tell us how Fangio would perform in a 2019 car, due to the different requirements of racing between those eras. We can only speculate as to how well abilities would translate as the discipline has evolved.

Mika Häkkinen driving a McLaren M23

When we observe systematic changes in ability between eras, it is not entirely clear what to attribute this to, whether it be better training, a larger talent pool, or other factors not explicitly represented within the model. Some readers will therefore be more comfortable looking at driver rankings within eras rather than across eras. The rankings generated within-eras are also more digestible.

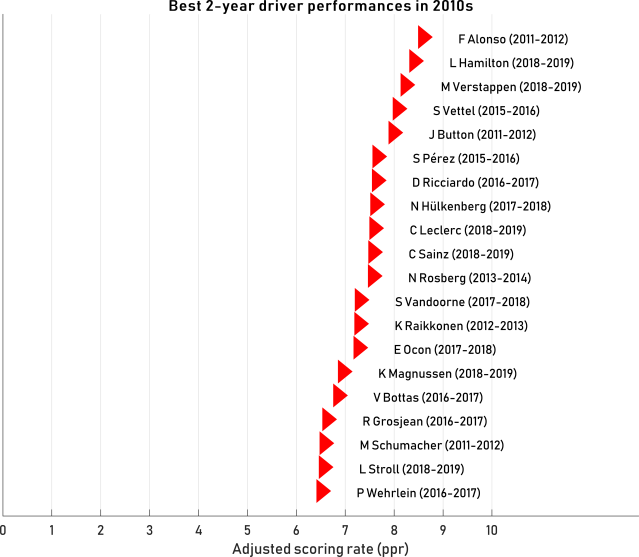

For this analysis, I asked who were the best performing drivers within each decade of the sport. Note that the model is still using all of the data from 1950-2019 to generate these estimates, we are just looking at outputs within a restricted time window. For these rankings, I used each driver’s strongest consecutive 2-year performance interval from each decade. I used 2 years here (rather than 3 years, which is the primary measure for the all-time top 100 list below) to better handle cases where a driver’s best years happened to overlap the beginning/end of a decade. For a year to be counted in the 2-year performance interval, I required that the driver have at least 2 counting races in the season (again, for high inclusivity).

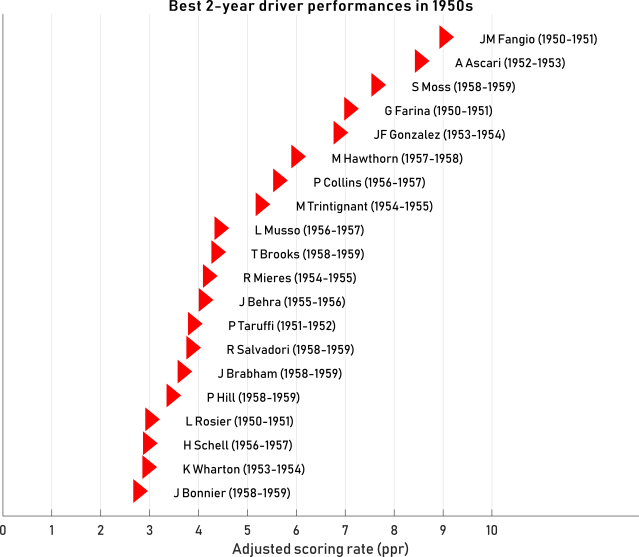

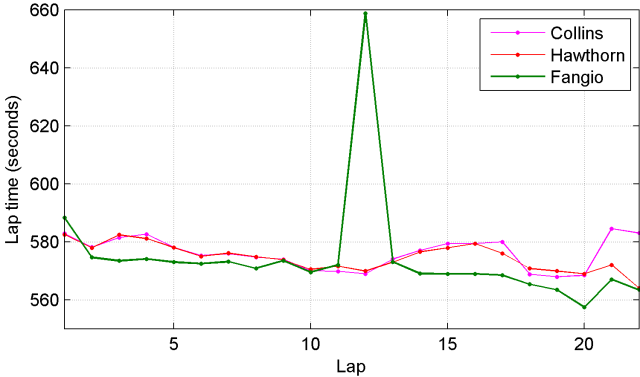

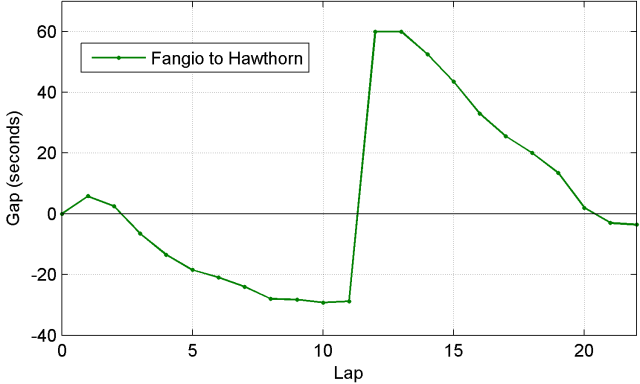

Two drivers stand clearly ahead of their peers in the 1950s. They are 5-time champion Juan Manuel Fangio and 2-time champion Alberto Ascari. Both were extremely dominant over their teammates, with Fangio only outqualified 12% of the time and Ascari 27% of the time by a teammate. Both drivers also held a strong positive head-to-head record as teammates to the 1950-champion, Giuseppe Farina. Fangio beat Farina 5-1 in counting races and 11-2 in qualifying. Ascari beat Farina 11-2 in counting races and 13-2 in qualifying.

Stirling Moss, not yet at the full height of his powers, and serving an understudy role to Fangio at Mercedes in the mid-1950s, is ranked the 3rd strongest performing driver of the decade. Giuseppe Farina and the largely underrated José Froilán González are ranked 4th and 5th, respectively. The only other driver in this era with a performance rating >6 ppr is the 1958 champion Mike Hawthorn.

As we move into the 1960s, three giants of motorsports clearly stand out. They are, respectively, Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart, and Stirling Moss. Temporally, their peaks did not really overlap due to tragic circumstances. Moss was at his absolute best in the early 1960s, when his F1 career was abruptly cut short at age 31 by a crash resulting in a severe head injury and a subsequent month-long coma. Jim Clark, who debuted in 1960, was at his peak in the early-to-mid 1960s. His career ought to have overlapped to a much greater degree with Stewart’s, but Clark died aged 32 in a 1968 Formula 2 race. Stewart’s own peak performances only began to emerge near the end of the decade, continuing into the 1970s.

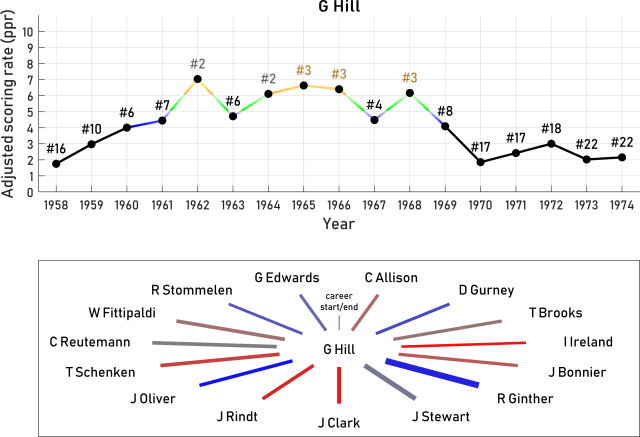

Behind these three drivers is a cast of four closely matched drivers with extraordinary legacies, all with performance ratings >6 ppr. They are World Drivers’ Champions Graham Hill (2-time champion) and Jochen Rindt (1-time champion), as well as famous car constructors Dan Gurney and Bruce McLaren. Just behind this group are rated Jack Brabham (3-time champion and the only constructor-driver champion in F1 history), John Surtees (1-time champion and 4-time 500cc champion), Denny Hulme (1-time champion), and sports car legend Jacky Ickx (6-time Le Mans winner). This is a group of drivers known as much for their driving skills in F1 as for their contributions outside of racing or success across disciplines.

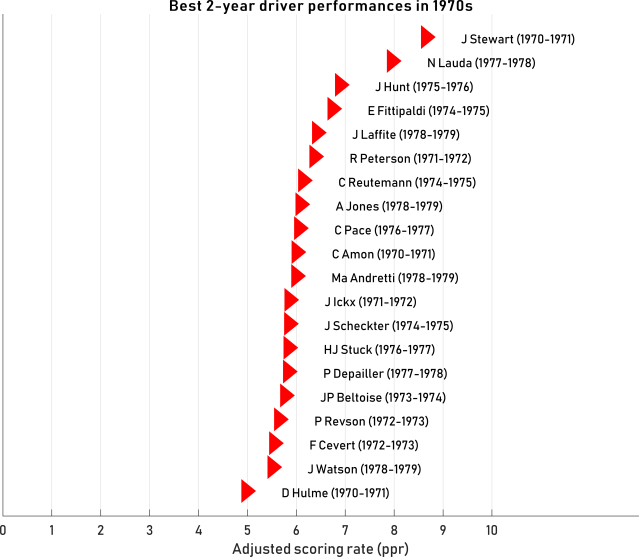

Jackie Stewart is rated the clear best driver of the 1970s, though Niki Lauda is not too far behind in 2nd place. Jochen Rindt sadly misses out due to the 2-year criterion; his 1970 performance, with a perfect win-rate in counting races, remains one of the model’s all-time top single-year performances.

The 1970s is an era of much sharper competition than the 1960s, with 15 drivers having performance ratings >6 ppr. James Hunt and Emerson Fittipaldi are rated closely as 3rd and 4th best of the era. Hunt, who was formerly the model’s 2nd ranked driver of the 1970s, ahead of Lauda, has moved down to 3rd place with the latest updates to the model. This is a result I explore in greater detail in his top 100 entry below.

We would naturally expect the 1980s to be a two-horse race between Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna. As the model sees it, Prost was the stronger performer of the pair in this period, while Senna was the stronger performer in the early 1990s. Prost’s 2-year peak spans his very strong 1985 and 1986 campaigns. Senna’s 2-year peak in the 1980s interestingly encompasses the same period. This can be attributed to the model giving 1988 to Prost, as he significantly outscored Senna on total points — debates can rage on about whether Senna might have driven differently under a different scoring system.

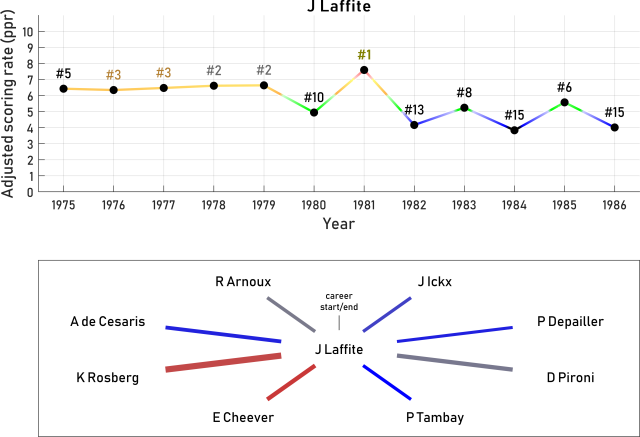

Behind Senna are four closely matched drivers. They are Keke Rosberg (1-time champion), Elio de Angelis (teammate to Nigel Mansell and Ayrton Senna), Jacques Laffite, and Nelson Piquet (3-time champion). de Angelis was ranked highly by the original f1metrics model on the back of his superior results against Mansell and his credible results against Senna; little has changed here. Laffite is ranked much higher once age and experience effects are taken into account. This is explained in his entry in the top 100 below.

Three other drivers of the 1980s have performance ratings >6 ppr. They are John Watson, Nigel Mansell, and Eddie Cheever. Among these three drivers, John Watson’s ranking is the most notable change from the original f1metrics model, which can be explained by the model now taking Niki Lauda’s comeback status and Alain Prost’s rookie status into account during times when they were Watson’s teammate.

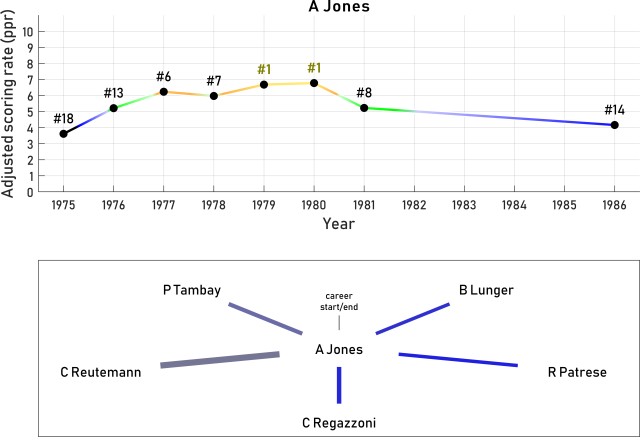

Niki Lauda features as the 10th best performer of the 1980s. His comeback and clever campaign to take the 1984 title remains one of the greatest achievements in F1 history. Nonetheless, the model recognizes that he was probably past his best at this stage of his career. Alan Jones, the 1980 champion, is rated lower than he was in the original f1metrics model rankings, largely because his peak straddles 1979-1980.

In the 1990s, Michael Schumacher stands alone at the top. The gap between his performance level and that of his peers is the most striking in F1 history. The next highest rated performances in the 1990s are those of Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost, who competed early in the decade, before Schumacher had reached his peak.

After that, the model sees a closely matched set of drivers. Rubens Barrichello and Eddie Irvine — drivers who were perhaps not given enough credit due to the enormity of the challenge from their teammate, Schumacher — and Heinz-Harald Frentzen, a driver who challenged Schumacher in other categories, but never quite reached his level in F1. Other champions of the 1990s appear next — Jacques Villeneuve, Nigel Mansell, Mika Häkkinen, and a few places further down is Damon Hill — all of whom won titles in dominant equipment.

The three other drivers of the 1990s with performance ratings >6 ppr are each stories of unfulfilled potential. Jean Alesi, who could in different circumstances have challenged for titles at Williams. Stefano Modena, who was brilliantly quick, but highly temperamental. And Mika Salo, who only got to cameo at Ferrari as Schumacher recovered from his 1999 injury, giving up his only chance at a race win to help Eddie Irvine’s title challenge.

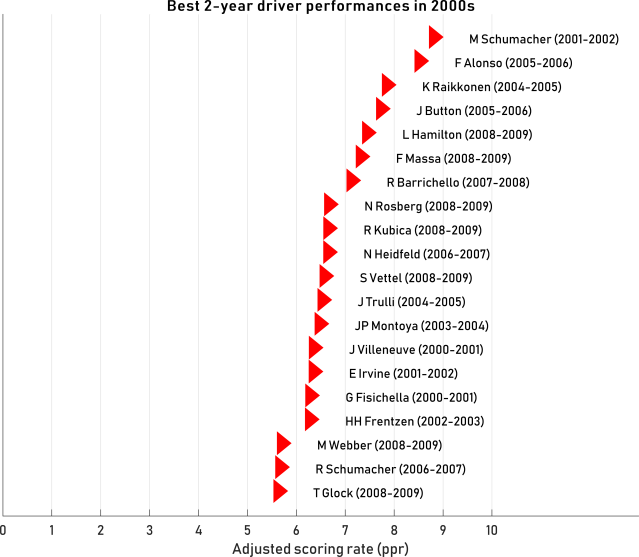

By the 2000s, the level of driving in F1 had improved as training methods became far more systematic and drivers began to adopt a fully professional approach. While there remained some very weak pay-drivers on the grid, there were 17 drivers in this decade with a performance rating >6 ppr, and 26 below this rating, meaning 40% were above the threshold.

Michael Schumacher is rated the top driver of the decade, but with a younger generation now in hot pursuit. Fernando Alonso is close behind in 2nd.

Kimi Räikkönen, though not at Schumacher or Alonso’s level, stands a clear 3rd in this era. By the model’s reckoning, Räikkönen did not capture this level again, which is explored in his driver entry in the top 100 below. Jenson Button slots in just behind Räikkönen, on the back of his impressive but largely unrewarded performances for Honda. He was somewhat a champion of circumstance for Brawn in 2009, but it was a deserved result given his abilities. Lewis Hamilton was not yet performing at his peak in this decade, being only in his third season by 2009, and having one of his weaker seasons in 2008. Despite this, he is already ranked 5th best of the decade.

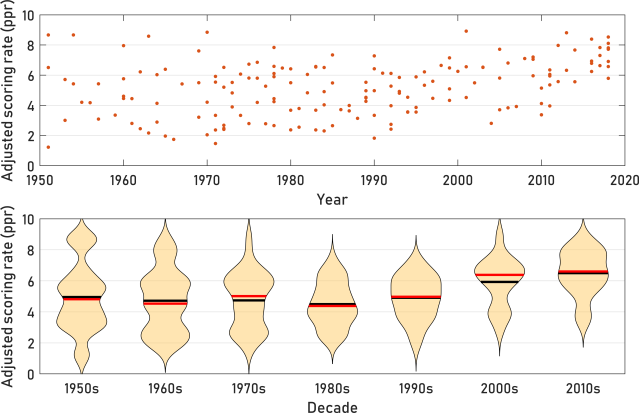

With fewer seats available due to teams folding, and with increasingly strict standards for F1 drivers (including stricter limits on superlicenses), the quality of the F1 grid reached an unprecedented level in the past decade. A total of 30 drivers in the 2010s have a performance rating >6 ppr, compared with 15 who do not, meaning 67% were above this threshold. This systematically rising (and compressing) level of driver quality is explored in more detail below.

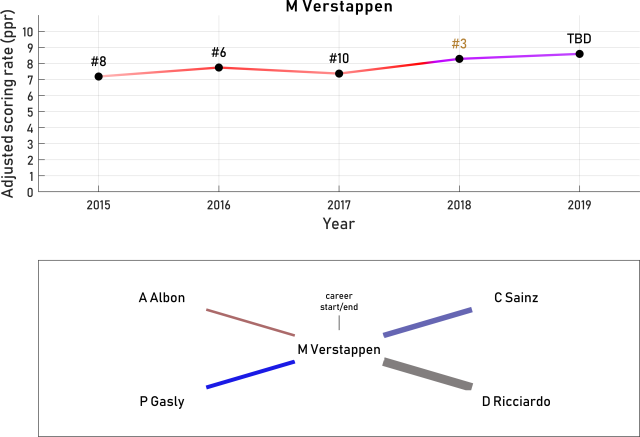

Within this exceptional cohort, two drivers are ranked clearly at the top of the era: Fernando Alonso and Lewis Hamilton. Ranked 3rd is currently Max Verstappen, on the strength of his excellent 2018-2019 performances. Sebastian Vettel is ranked 4th, on account of not having ever strung two extremely strong seasons together consecutively for a 2-year peak. Combining any two of his 2011, 2013, 2015, or 2017 performances would elevate him to 3rd. Jenson Button rounds out the top 5 of the decade, just ahead of a closely matched throng of six drivers.

THE ALL-TIME TOP 100

Last time I made an all-time driver ranking list, I presented the top 60 drivers. I thought it would be better to expand it to the top 100 drivers this time around, given there was considerable interest in seeing lower ranked drivers.

One of the most obvious changes that we observe with the updated model is a preference shift towards modern drivers.

Of the top 30 drivers in the list, 11 were actively racing in 2019. This shift is apparent from the above ratings by era.

Whereas only six drivers in the 1950s had a performance rating >6 ppr, all of the top 20 drivers in the 2010s exceeded this threshold. While there were individual, very strong performers in earlier eras, the depth of the field was much weaker.

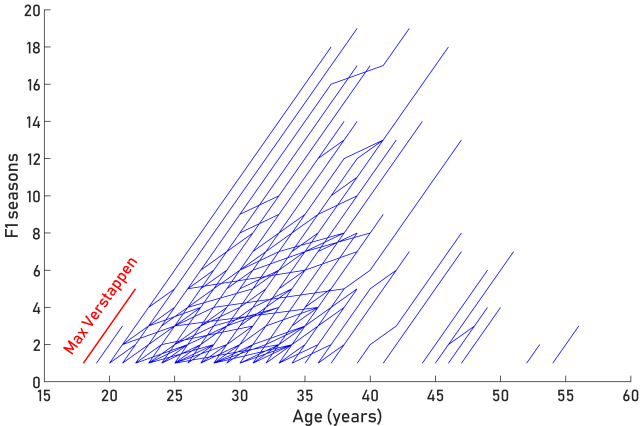

The evolving abilities of F1 drivers. Each dot in the top graph represents the 3-year peak of a single driver. The bottom graph shows the distribution of peak performances within each decade as violin plots. Note the progressive loss of the lower tail over time.

I think this finding should probably come as no great surprise in a model that correctly incorporates the roles of age and experience. The quality of training for drivers today is simply unlike that of their predecessors. At the age that Max Verstappen debuted in F1, having already trained for a decade in go-karts and honing his craft using telemetry, simracing, and other modern training tools, luminaries such as Jim Clark, Juan Manuel Fangio, and Jackie Stewart were yet to even start any type of amateur racing. While we could try to speculate how Fangio or Stewart might have performed had they been given a go-kart at age 4, answering that question is not the goal of this exercise, nor something that the model is yet capable of predicting (since pre-F1 experience is not a predictive factor in the model).

Many of the drivers of the 1950s were aged over 40, some returning from substantial career gaps. While the top drivers of that era were undoubtedly extraordinary talents, the drop off in quality of the field was clearly much steeper.

Age of drivers in the year of their championship debut. This plot uses all drivers in the f1metrics database, which requires that they completed at least 3 counting races in a single season. Darker dots represent multiple overlapping drivers.

What this means is that even the worst drivers on the grid today are comparable to drivers who we would have considered quite strong in previous eras. Given a time machine, could drivers such as Sainz and Pérez keep pace with Senna or Prost? The model answers ‘probably yes’, as we will see in the top 100 list below.

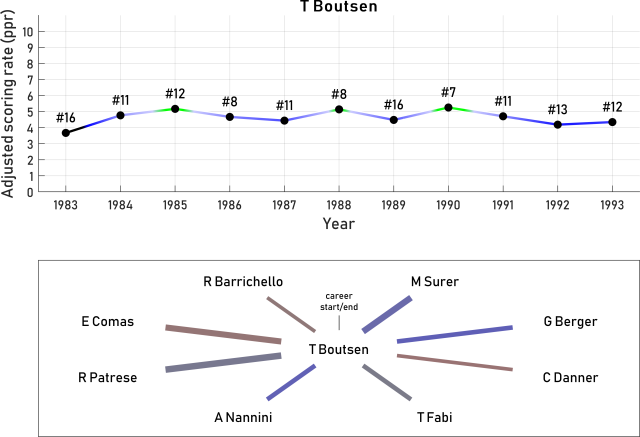

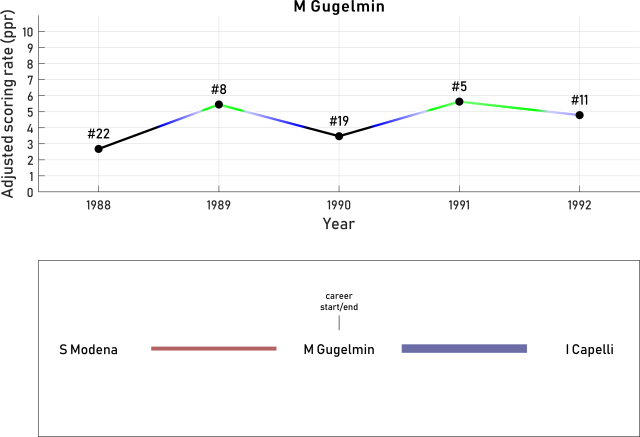

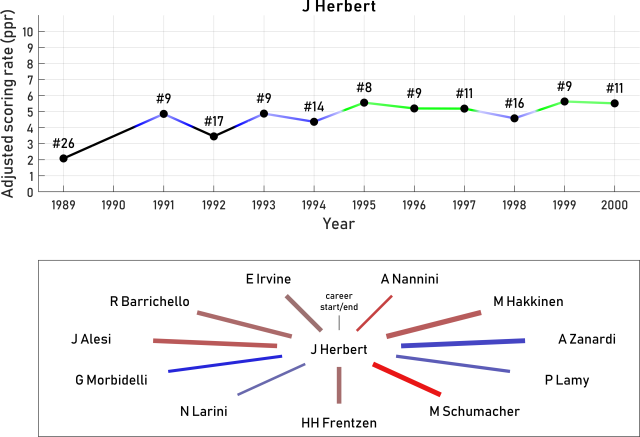

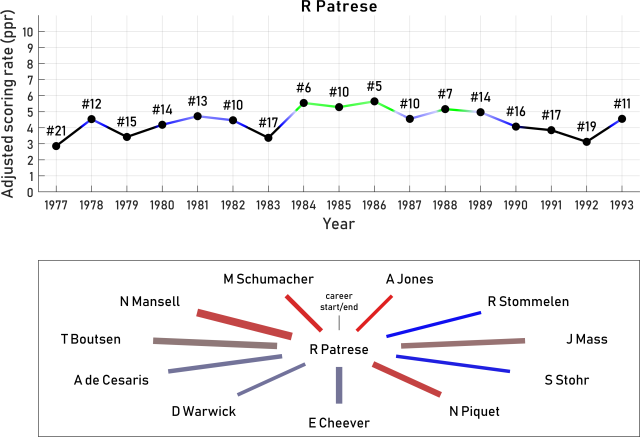

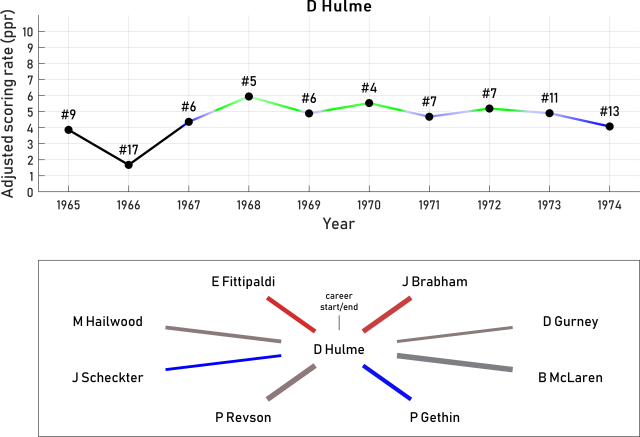

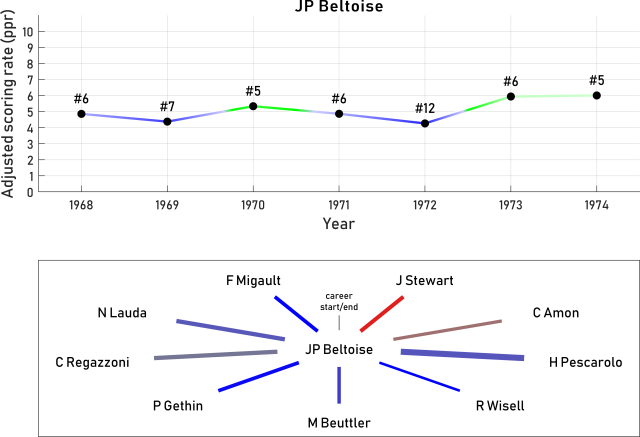

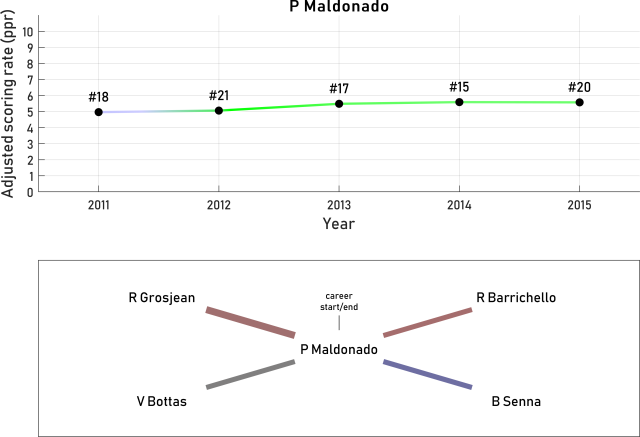

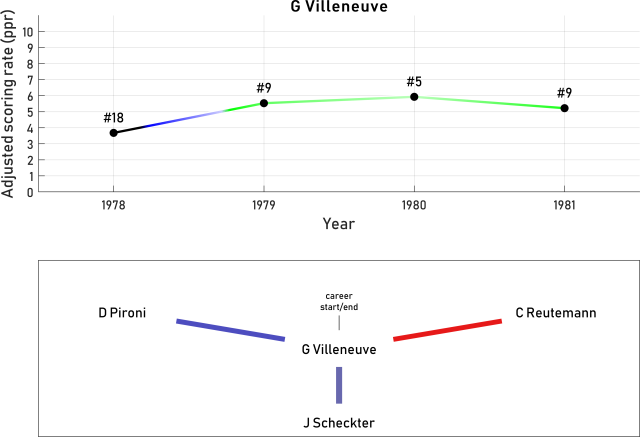

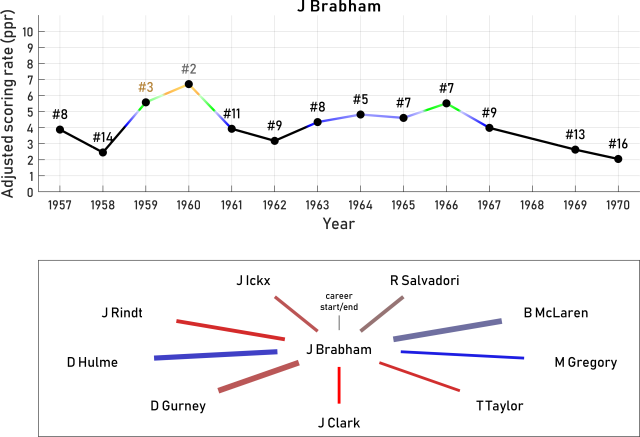

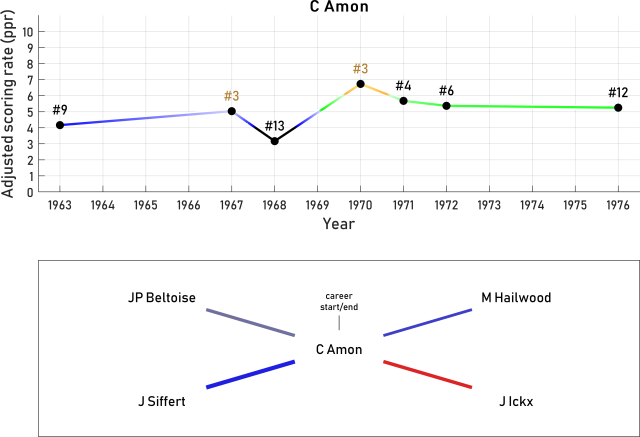

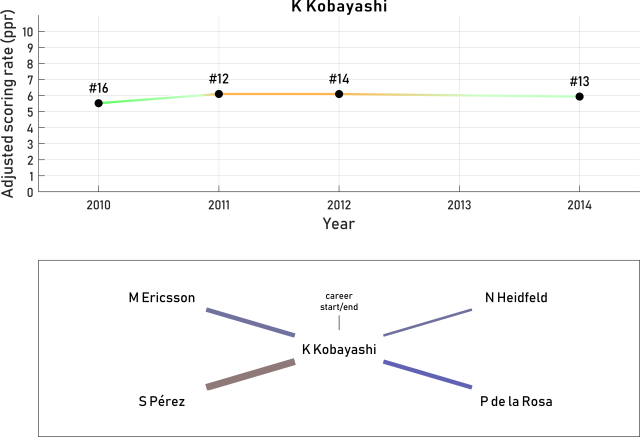

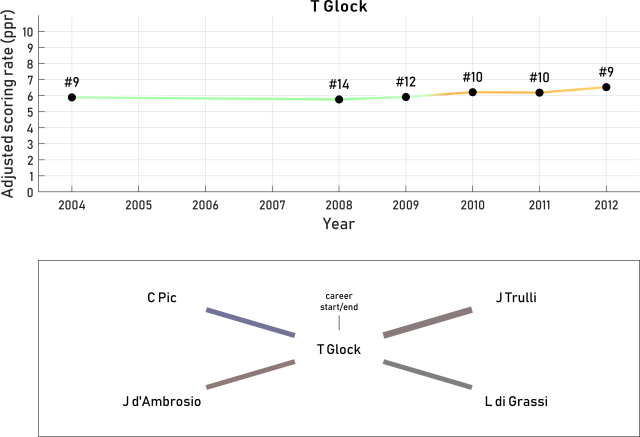

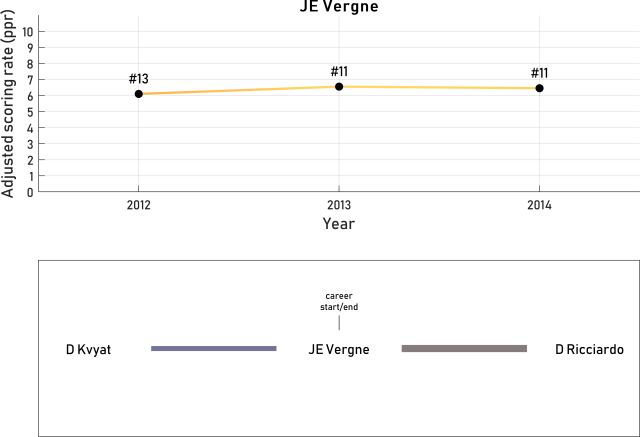

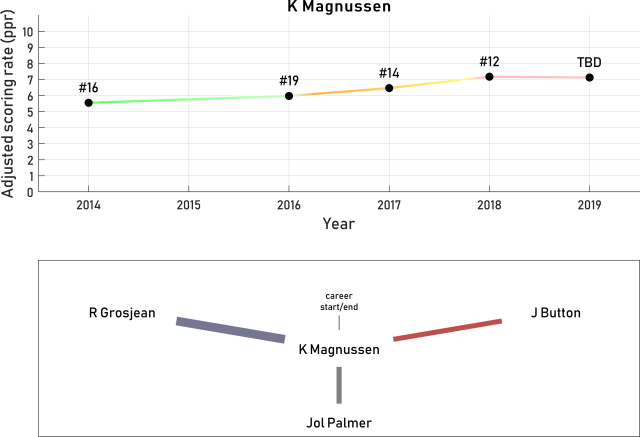

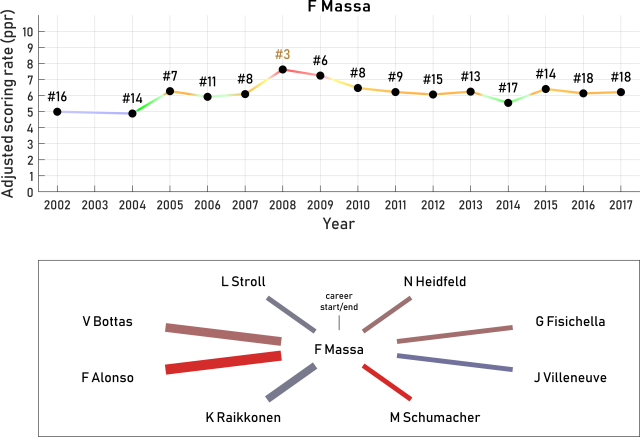

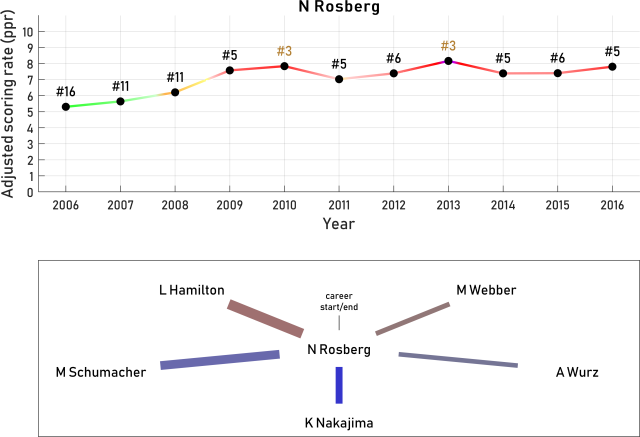

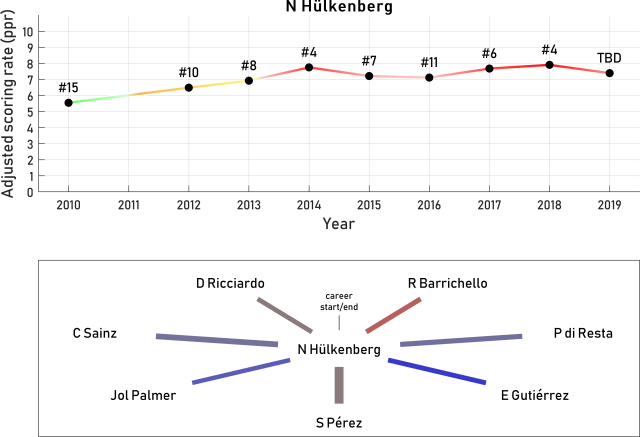

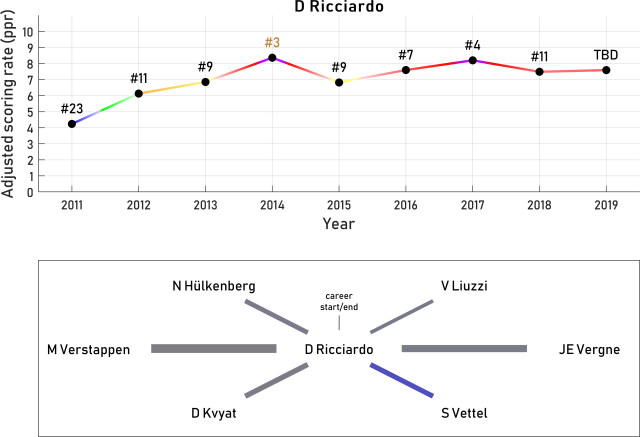

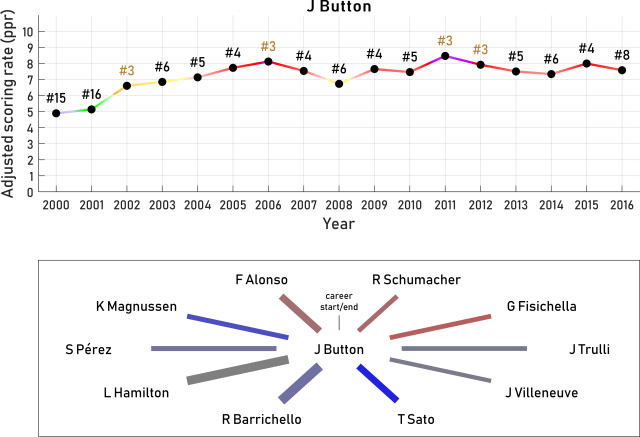

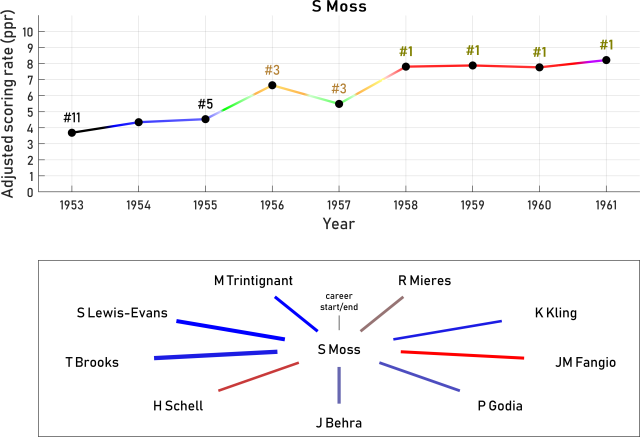

In each driver’s profile, I have included a graphic like the example for Rubens Barrichello below.

The top half of this graphic shows the driver’s estimated performance level in each season, on the normalized 0-10 scale of points per race (ppr), with the color of the line corresponding to the ppr level. For seasons where the driver completed the minimum required counting races, their ranking relative to other drivers in the same season is also displayed.

The bottom half of this graphic shows the driver’s teammate connections, revealing an approximation of how the model sees each teammate connection. Connections are shown with at least 2 counting races in the same car together. Although the model uses all the historical data, drivers are only illustrated as teammates here if they had the same chassis-engine and the same customer/non-customer status (i.e., both works or both customers). The thickness of the line is scaled by the number of races together.

The color of the teammate connection indicates the drivers’ relative performances in their seasons together, as a weighted average if they had multiple seasons together. Blue indicates that the profiled driver outperformed their teammate, gray indicates that it was close to equal, red indicates that they were outperformed by their teammate. Note that these comparisons consider each driver’s full performance in the given car that season (i.e., it may include races which only one of the drivers started, under the assumption that car performance is relatively constant across a season). The driver’s career circulates clockwise, beginning and ending at 12’o’clock.

In each driver’s entry, I have also reported some head-to-head results relative to teammates, including results in counting races (excluding non-driver DNFs for either driver, such as mechanical failures or technical disqualifications), qualifying, and points.

So, let’s start the list!

100. Chico Serra

(4.83 ppr, 1981-1983)

Before Ayrton Senna, there was Chico Serra, a Brazilian multiple-time karting champion who won British Formula Ford, followed by the British F3 title, then was promoted to F1. Unlike Senna, Serra never really caught a break in F1, spending his two full seasons at the hopelessly uncompetitive Fittipaldi team, where even teammate Keke Rosberg struggled to qualify the car. Serra was clearly outpaced by the more experienced Rosberg, scoring 1-1 in counting races but 0-14 in qualifying against the future champion.

99. Clay Regazzoni

(4.83 ppr, 1972-1974)

Clay Regazzoni raced against an impressive cast of teammates, including three champions (Mario Andretti, Niki Lauda, and Alan Jones) and one near-champion (Jacky Ickx). Regazzoni was quick enough to challenge Andretti, outqualifying him 4-1 but trailing 0-3 in counting races. During their first season as teammates (Lauda’s second full F1 season), Regazzoni beat Lauda 3-2 in counting races and 8-5 in qualifying. Once Lauda found his feet in F1, Regazzoni was outclassed: across the following three seasons, Regazzoni was beaten 6-15 in counting races and 3-40 in qualifying. It was a similar story against Jones, as Regazzoni was beaten 1-6 in counting races and 0-15 in qualifying, although by this time Regazzoni was turning 40. His F1 career was sadly ended by serious injuries after a brake failure at Long Beach the following year.

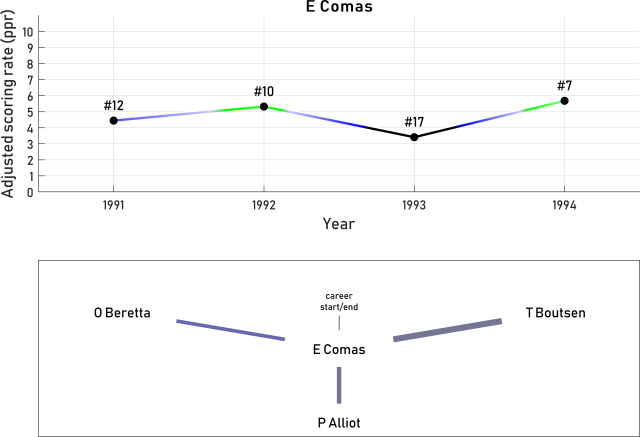

98. Érik Comas

(4.92 ppr, 1992-1994)

Érik Comas was a highly promising junior single-seater driver. After winning the French Formula Renault and F3 titles, he graduated to F3000, losing the title on count-back to Jean Alesi in his rookie season and easily winning the title the following year. In 1991, he debuted for Ligier in F1, where he raced for two seasons alongside the more experienced Thierry Boutsen. Although beaten 9-23 in qualifying by Boutsen, he was ahead 10-2 in counting races and 4-2 in points. The teammates collided twice in 1992, souring the relationship.

A move to Larrousse in 1993 brought no better results. In an extremely unreliable car, Comas faced teammate Philippe Alliot (ranked 144th) for 1993 and one race in 1994, scoring 6-9 in qualifying, 2-2 in counting races, and 1-2 in points. Comas spent most of 1994 alongside the rookie Olivier Beretta (no ranking), outperforming him 3-1 in counting races, 10-0 in qualifying, and 2-0 in points. No F1 seat was forthcoming for 1995, meaning Comas moved to endurance racing.

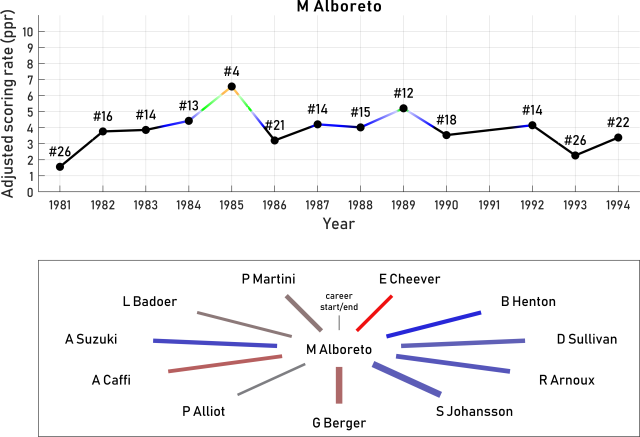

97. Michele Alboreto

(4.93 ppr, 1983-1985)

Michele Alboreto’s crowning achievement was undoubtedly his 1985 season, where he challenged Alain Prost for the title until poor reliability ended the campaign.

As a rookie, Alboreto was soundly beaten by his more experienced teammate Eddie Cheever 4-8 in qualifying, 0-3 in counting races, and 0-10 in points. Results improved over the following two years, culminating with a Ferrari seat alongside Rene Arnoux (ranked 130th) for 1984.

Critically, after arriving at Ferrari, Alboreto established his reputation by beating Arnoux 6-2 in counting races, 14-3 in qualifying, and 33.5-30 in points. With Arnoux displaced from the team in early 1985, Alboreto became the de-facto team leader, right as Ferrari produced a potential championship challenger, allowing Alboreto his most successful season. Over 1985-1986, he beat teammate Stefan Johansson (ranked 129th) 9-4 in counting races, 24-7 in qualifying, and 61-49 in points.

Subsequent results for Alboreto were very mixed. Against Gerhard Berger at Ferrari across 1987-1988, he was heavily beaten 3-10 in counting races, 4-28 in qualifying, and 41-77 in points, ending Alboreto’s relationship with the team. After Frank Williams reneged on a Williams offer for 1989, Alboreto spent the rest of his career in lower midfield and backmarker cars.

96. Thierry Boutsen

(4.97 ppr, 1988-1990)

Thierry Boutsen was a reliable and quick driver who occasionally starred in the 1980s and early 1990s, most notably at Benetton and Williams, but never really broke through to the level of a top driver. The machinery he had at his disposal was only intermittently good enough to challenge for wins.

Boutsen was a wet-weather specialist, with two of his three wins coming in wet conditions. As I have shown in a previous post, Boutsen ranks among the top drivers when comparing wet-weather scoring rates to dry-weather scoring rates. By the model’s reckoning, Boutsen was at his best in 1990, when he raced alongside Riccardo Patrese and won the Hungarian GP from pole (his only dry race victory). He outscored Patrese 34-23 to finish sixth in the championship.

95. Maurício Gugelmin

(4.99 ppr, 1989-1991)

Maurício Gugelmin’s F1 career was stymied by uncompetitive and unreliable cars. Mechanical DNFs comprised 49% of his race starts. Most of his career was spent racing for Leyton House, four times finishing in the points.

Gugelmin primarily raced alongside two teammates in F1. The first was Ivan Capelli (ranked 112th), who was entering his second full season when Gugelmin debuted. Gugelmin scored 20-25 in qualifying, 6-6 in counting races, and 9-18 in points, with his record progressively improving versus Capelli as he gained experience, whereas the car’s competitiveness and points scoring opportunities faded away. This left Capelli ahead in the overall points tally, based on their first season together, but the model recognizes that Gugelmin was the slightly better performer across seasons, adjusting for car performance.

The second teammate was Stefano Modena, who raced alongside Gugelmin in the uncompetitive 1992 Jordan. Modena appeared to have a slight edge over Gugelmin, with Gugelmin scoring 2-2 in counting races, 7-9 in qualifying, and 0-1 in points.

94. Pedro Diniz

(5.08 ppr, 1998-2000)

Pedro Diniz was a pay-driver supported by a billionaire father, who proved to have respectable but not top-line pace when faced with a series of highly talented teammates.

Diniz’s junior results were underwhelming, and would not have justified a move to F1, were it not for the struggling Forti team desperately seeking investors. In his rookie year, Diniz exceeded expectations by looking competitive alongside his experienced teammate, the 35-year-old Roberto Moreno (no ranking). The overall tally for Diniz was 5-2 in counting races and 8-9 in qualifying. For 1996, Diniz jumped ship to Ligier, a team in the doldrums and very eager to receive Diniz’s financial support. Partnered with the promising Olivier Panis (now in his third season), Diniz was clearly outpaced 3-5 in counting races, 1-15 in qualifying, and 2-13 in points.

For 1997, Diniz was paired with reigning champion, Damon Hill, at Arrows. Beaten but not completely embarrassed by Hill, Diniz trailed 2-3 in counting races, 3-14 in qualifying, and 2-7 in points. Results against Jean Alesi and Mika Salo in subsequent seasons further confirmed Diniz’s status as competent, but never quick enough to reliably beat top drivers.

One of the key factors that held Diniz back from achieving more was his incredibly high crash rate. Diniz crashed out of 27.6% of his F1 starts (or 41.5% of his counting races), which is the highest crash rate of anyone in the top 100. He also holds the all-time record for the most consecutive crash-related DNFs in F1 history, with 6 consecutive crashes from Germany 1999 to Malaysia 1999.

93. Adrian Sutil

(5.12 ppr, 2009-2011)

Adrian Sutil showed occasional glimpses of promising speed, most often at Monaco. In his second full season, he memorably lost a 4th place finish with just six laps to go when hit from behind by an out-of-control Kimi Räikkönen. However, Sutil was forever held back by inconsistency. His crash rate of 19% was one of the highest of the modern era.

Sutil was clearly quicker than Vitantonio Liuzzi (ranked 118th), whom he beat 10-9 in counting races, 17-4 in qualifying, and 47-21 in points. But he clearly struggled against Giancarlo Fisichella, whom he trailed 8-12 in counting races, 14-20 in qualifying, and 0-8 in points.

92. François Cevert

(5.20 ppr, 1971-1973)

François Cevert spent his career racing alongside one of the all-time greats, Jackie Stewart. Cevert was nurtured and coached by Stewart as his protégé and heir apparent at the Tyrrell team. Unfortunately, Cevert died in a horrifying crash in qualifying for what would have been Stewart’s final grand prix, meaning he never took the leading driver role.

Overall, Cevert was dominated by Stewart, trailing him 6-24 in counting races, 5-37 in qualifying, and 83-190 in points. The qualifying gap between the pair was substantial but decreased over time, as shown below.

Percentage qualifying gaps from Cevert to Stewart. Negative values indicate that Cevert is quicker, positive values indicate that Stewart is quicker. Each data point is one qualifying session. Dashed horizontal lines indicate median values for each season.

Cevert is also linked with Ronnie Peterson in the above teammate graphic, as both drove a customer March-Ford in 1970, although for different entrants (Cevert for Tyrrell, Peterson for the less well funded Colin Crabbe racing team — a fine detail that the model does not account for).

Projecting Cevert’s likely career, had he survived, was the topic of a recent post in my historical hypothetical series. The conclusion of that analysis was that Cevert would have likely won several races for Tyrrell, but probably would not have ever won a drivers’ title.

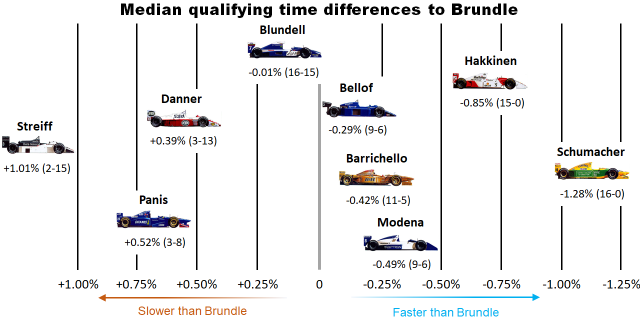

91. Martin Brundle

(5.27 ppr, 1991-1993)

Although he never secured a top drive, Martin Brundle faced an incredible array of highly rated teammates across his career, including Michael Schumacher, Mika Häkkinen, Rubens Barrichello, Olivier Panis, and Stefano Modena. This assortment of teammates allows a strong determination of Brundle’s level relative to others. In the plot below, reproduced from my historical hypothetical series, we can see how Brundle’s qualifying performances rated relative to each of his teammates.

Brundle was a highly versatile driver who excelled in both F1 and sportscars. The fact that he failed to win an F1 race was more reflective of machinery than the quality of his driving. In Brundle’s 158 starts, he scored 9 podiums. His teammates scored 18 podiums, with only a single win by Michael Schumacher at Belgium 1992.

Brundle was a reliable pair of hands in race conditions, even if he lacked somewhat in ultimate pace. In the words of Ron Dennis, at the time when Brundle was being replaced by David Coulthard,

“He struggles in qualifying and does a brilliant job in the race. When you start two or three rows back from where you should be, you don’t get a chance to shine.”

A major unresolved question over Brundle’s career is whether he might have performed better had he not suffered major injury in his brutal crash at Dallas 1984, which prevented him left foot braking later in his career. Brundle survived several other major accidents, including a direct strike from a car to his helmet at Brazil 1994 resulting in severe concussion, another concussion at Monaco 1984, and a famous crash in Melbourne 1996, where his car split into two pieces. We are all fortunate that he survived such a challenging career to work in the commentary booth.

90. Hans-Joachim Stuck

(5.28 ppr, 1976-1978)

Hans-Joachim Stuck was an absolute legend in sportscars and sedans, but struggled to find the same success in F1. Stuck was not helped in single-seaters by his very large frame (194cm, 6’4″). In F1, he was also frequently driving beyond the limit, crashing out of an extraordinary 27% of the races he started.

Stuck started his F1 career at March, where he was joined by fellow rookie Vittorio Brambilla (ranked 114th). The pair raced together for three seasons, with Stuck scoring 2-6 in counting races, 14-20 in qualifying, and 13-12 in points. In his third season at March, Stuck was also joined by teammate Ronnie Peterson, against whom Stuck scored 2-2 in counting races, 2-13 in qualifying, and 5-10 in points.

Following the tragic death of Carlos Pace, Stuck raced for Brabham in 1977. There, he was paired with John Watson, against whom he scored 2-3 in counting races, 3-11 in qualifying, and 12-8 in points. Stuck’s final move in F1 was to the Shadow team, where he raced alongside Clay Regazzoni, scoring 0-2 in counting races, 6-9 in qualifying, and 2-4 in points.

89. Vitaly Petrov

(5.33 ppr, 2010-2012)

Vitaly Petrov is perhaps best known for his pivotal role in the 2010 championship decider, as he used every inch of track and more to deflect Fernando Alonso. Having taken four years to achieve 2nd in the championship in GP2, expectations were not high for Petrov when he debuted at Renault alongside the more experienced Robert Kubica in 2010. The one-sided tally of 1-13 in counting races, 2-17 in qualifying, and 27-136 in points confirmed initial expectations.

Following the unfortunate injury of Kubica, Petrov mounted a much more successful second season in 2011. Beginning the season alongside veteran Nick Heidfeld, Petrov achieved the very credible record of 4-6 in counting races, 8-3 in qualifying, and 32-34 in points. When Bruno Senna (ranked 123rd) replaced Heidfeld midseason, Petrov prevailed 5-3 in counting races, 4-4 in counting races, and 5-2 in points.

In his final season, Petrov raced alongside Heikki Kovalainen. Although neither driver scored points in the uncompetitive Caterham CT01, Petrov came out ahead 10-7 in counting races and was behind 6-13 in qualifying. Neither driver was retained for the 2013 season.

88. Johnny Herbert

(5.33 ppr, 1995-1997)

Like Martin Brundle, one wonders what more Johnny Herbert might have achieved had he not carried permanent foot injuries throughout his F1 career. After a dominant title in British F3 in 1987, beating 8 future F1 drivers, Herbert was considered an extremely hot prospect. Following a devastating crash in F3000 that almost resulted in foot amputation, he was fortunate to still find an F1 seat, scoring points incredibly on his debut for Benetton. Herbert’s performance tailed off due to difficulty braking with his damaged foot, but he found a more permanent home at Lotus. From 1991-1992, Herbert faced the younger, less experienced Mika Häkkinen. While Herbert came out ahead 14-10 in qualifying — impressively given Häkkinen’s later record in qualifying — he trailed 2-7 in counting races.

After positive results against Alex Zanardi (no ranking) and Pedro Lamy (ranked 126th), Herbert was recruited by Benetton as Michael Schumacher’s number two, supporting his title challenge in 1995. Up against one of the greatest drivers in history, Herbert was dominated 3-12 in counting races, 1-18 in qualifying, and 45-108 in points. Herbert’s victory at the British GP came as a result of Schumacher and Hill colliding, as well as Coulthard receiving a stop-go penalty after a failure of the pit speed-limiter.

Herbert’s subsequent records against Heinz-Harald Frentzen, Rubens Barrichello, Jean Alesi, and Eddie Irvine confirmed that he was a solid driver, but never among the top drivers on the grid.

87. Maurice Trintignant

(5.42 ppr, 1953-1955)

Maurice Trintignant had an impressively varied racing career, beginning in 1938 at age 21 and resuming after World War II. Unlike most pre-war racers, he was still relatively young, aged 32, at the beginning of the World Drivers’ Championship in 1950. This allowed him to enjoy a long F1 career, which stretched out until 1964. In fact, Trintignant held the record for most F1 starts from 1959 to 1966 before Jack Brabham and Graham Hill took the record. Notably, Trintignant spent 61% of his counting races in customer cars, which the model now considers in cases such as his negative records against works team drivers Jack Brabham (who beat Trintignant 4-10 in counting races) and Bruce McLaren (who beat Trintignant 2-4 in counting races).

The model rates Trintigant the season’s 3rd best performer on two occasions: in 1955, when he raced for Ferrari, outscoring teammate Giuseppe Farina, and again in 1958. Both were years in which he won the Monaco GP — curiously, the only track at which he ever won.

86. John Surtees

(5.42 ppr, 1966-1968)

John Surtees achieved the almost unbelievable distinction of winning the highest level championships on both two wheels and four wheels. That in itself is one of the greatest ever achievements in motorsports.

In F1, Surtees held a consistent advantage over his long-time number two driver, Lorenzo Bandini (ranked 167th), beating him 7-1 in counting races, 21-3 in qualifying, and 66-47 in points. Surtees also held a collective record of 9-5 in counting races against a rotating cast of moderately strong teammates, none of whom make the top 100 (Roy Salvadori, Masten Gregory, Ian Burgess, Innes Ireland, Jackie Lewis, Pedro Rodriguez, Mike Hailwood, and Willy Mairesse).

Surtees completed only a small number of races against other world champions across his career. In his rookie season for Team Lotus, Surtees was paired with fellow rookie Jim Clark, scoring 1-1 in counting races, 1-2 in qualifying, and 6-4 in points, courtesy of an impressive 2nd place in only his second race start.

In 1966, Surtees split with Ferrari, racing a Cooper alongside Jochen Rindt. Against Rindt, Surtees scored 1-1 in counting races, 6-1 in qualifying, and 19-18 in points, despite 4 mechanical DNFs to Rindt’s 1. It was only Rindt’s second full season, which the model now takes into account for this comparison. Nevertheless, given how highly the model rates Rindt, this is considered Surtees’ career-strongest performance by some margin. It is notably, however, based on a small sample, with Surtees having only four counting races in the season.

85. Peter Collins

(5.43 ppr, 1956-1958)

Peter Collins famously gave away his own chance at challenging for the 1956 title to support teammate Juan Manuel Fangio, giving his car to the team’s lead driver mid-race while the title was still alive for both drivers. The model rates 1956 as Collins’ strongest season, rating him the year’s second best performer, behind only Fangio.

His contemporary, Tony Brooks, once said that Collins drove harder than any other driver he faced. Indeed, for a driver in the 1950s, Collins had a distinctly high crash rate of 1 in 8 starts. Only two drivers who debuted in the 1950s and started at least 20 races had higher crash rates than Collins: Luigi Musso (17%) and Johnny Claes (22%). Like Musso, Collins sadly died in a crash while chasing another driver down for the race lead.

84. David Coulthard

(5.48 ppr, 2001-2003)

David Coulthard’s career was curiously entwined with that of the legendary designer, Adrian Newey. The two worked together at Williams from 1994-1995, before Coulthard moved to McLaren in 1996. Newey also moved to McLaren in 1997, where the two remained until 2005, when Coulthard transferred to Red Bull to make way for Juan Pablo Montoya’s entry at McLaren. Once again, Newey followed Coulthard’s move a year later.

Intersecting with Newey for all but two years of his career ensured Coulthard access to consistently excellent machinery and results. His total of 13 career wins ranks 22nd in the all-time record books, ahead of numerous World Drivers’ Champions. Yet, to put these results in perspective, his teammates (Damon Hill, Mika Häkkinen, and Kimi Räikkönen) collectively racked up 31 wins over the same period.

83. Riccardo Patrese

(5.49 ppr, 1984-1986)

Riccardo Patrese experienced a baptism of fire, debuting alongside the more experienced Alan Jones at Shadow, and being bullied by senior drivers over his falsely represented role in Ronnie Peterson’s fatal accident in 1978. Beaten by Jones 0-5 in counting races, 3-6 in qualifying, and 1-13 in points, Patrese made a stronger impression in 1978, nearly winning in South Africa, but for an engine failure with 15 laps to go, and finishing on the podium in Sweden. He dominated his teammate Rolf Stommelen (ranked 162nd) 4-0 in counting races, 13-0 in qualifying, and 11-0 in points.

Across 1979-1980, Patrese was closely matched with teammate Jochen Mass (ranked 107th), scoring 7-6 in counting races, 20-6 in qualifying, and 9-7 in points. In 1981, he dominated the relatively weak rookie Siegfried Stohr (no ranking). 1982 was a major career move for Patrese, as he joined reigning champion Nelson Piquet at Brabham. In a turbulent season, Patrese outscored Piquet by 1 point, but very poor reliability for both cars made it a difficult comparison. In 1983, Brabham bounced back with a much stronger car, in which Piquet won his second championship, while Patrese finished only 9th in the championship, crashing out of the lead in Imola. Overall, Patrese’s head-to-head versus Piquet was 3-4 in counting races, 11-19 in qualifying, and 34-79 in points.

Frustrated by contract negotiations with Brabham team owner Bernie Ecclestone, Patrese signed for Alfa for 1984-1985, where he raced with Eddie Cheever, against whom he scored 4-1 in counting races, 20-12 in qualifying, and 8-3 in points.

Returning to Brabham, Patrese started 1986 alongside Elio de Angelis, before his teammate was tragically killed in testing. The pair finished no races together, but Patrese was leading 4-0 in qualifying and 1-0 in points after four rounds. Patrese partnered Derek Warwick for the rest of the season, beating him 2-0 in counting races, 8-3 in qualifying, and 1-0 in points. Continuing with Brabham in 1987, Patrese beat Andrea de Cesaris (ranked 122nd) 1-0 in counting races, 12-3 in qualifying, and 6-4 in points.

Patrese’s last major career move was to Williams, where he raced with Nigel Mansell and Thierry Boutsen. Patrese struggled against both drivers, losing to Mansell 5-20 in counting races, 12-34 in qualifying, and 117-192 in points, and losing to Boutsen 5-10 in counting races, 19-13 in qualifying, and 63-71 in points.

Patrese rounded out his long career, now aged 39, with a season at Benetton alongside the rapidly rising Michael Schumacher in 1993. Patrese was completely dominated, losing 1-7 in counting races, 0-16 in qualifying, and 20-52 in points.

At his best, Patrese was a driver capable of beating most others on the grid, but his limitations were evident whenever placed alongside an elite driver. The model rates 1984-1986 as Patrese’s career peak, which unfortunately coincided with some of his least competitive cars.

82. Denny Hulme

(5.50 ppr, 1968-1970)

Denny Hulme was part of a trio of extremely talented drivers from New Zealand in the 1960s, the other members being Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon. Of the three, Hulme was the most successful, winning 8 races and a drivers’ title. By the model’s rankings, however, Hulme is rated lowest of the three.

Hulme was a smooth, conservative, and tenacious racer. He crashed out of only 4% of his races and scored 9 fastest laps. However, he was a relatively weak qualifier, scoring only one pole position, the fewest of any world champion, while his teammates collectively scored 7.

Hulme began his career at Brabham, alongside the double-champion team-owner, Jack Brabham. Over three seasons, Hulme was beaten 3-9 in counting races, 5-20 in qualifying, and 69-95 in points. Within this period, Brabham won the 1966 drivers’ title, while Hulme won the 1967 drivers’ title. It is often claimed that Hulme won his title largely because Brabham experienced poorer reliability due to testing experimental parts. It is not, however, so straightforward.

Both drivers were affected by mechanical issues in South Africa, with engine issues dropping Brabham from 2nd to 6th, while Hulme’s loss of brake fluid dropped him from 1st to 4th. In Monaco, Brabham qualified on pole and likely could have won, relegating Hulme to 2nd, had his engine not failed. When both cars broke down in Belgium, Brabham was running 3rd while Hulme was outside the points. In Germany, Brabham’s qualifying position was poor due to running the old car, following a terrifying, high-speed suspension failure in practice. It is not clear that this meaningfully affected the race result, however. In Italy, Hulme was leading and likely could have won, relegating Brabham to 3rd, had his car not had a head gasket failure. Finally, Brabham dropped from 4th to 5th in the US due to a puncture.

Were these misfortunes in 1967 all reversed, Hulme would have scored 63 points, of which 59 would count for the championship due to the points system in that year excluding two results. Brabham would have scored 65 points, of which 59 would also count. In this hypothetical, both drivers would have 3 wins and 4 second places, meaning the title would go to Hulme on the basis of having 3 third places to 2 third places for Brabham.

Hulme moved to McLaren in 1968, racing alongside another team-owner/driver, Bruce McLaren. Across two seasons the pair were closely matched, with Hulme scoring 6-5 in counting races, 20-5 in qualifying, and 51-54 in points. Hulme was similarly closely matched with Pete Revson (no ranking), scoring 8-9 in counting races, 14-9 in qualifying, and 53-61 in points.

In his final F1 season, Hulme faced Emerson Fittipaldi. Now aged 38, and up against Fittipaldi in his prime, Hulme was comprehensively beaten 1-8 in counting races, 1-14 in qualifying, and 20-55 in points.

81. Derek Warwick

(5.52 ppr, 1988-1990)

Derek Warwick’s F1 career was filled with misfortune, meaning his race-winning potential was never realized. At his peak, the model sees Warwick as an extremely capable driver, ranked #4 in both the 1988 and 1989 seasons.

Several factors played into Warwick’s challenging career. First, he began at the uncompetitive Toleman team, during which time their car was often not quick enough to even qualify for the race. Second, a timely move to Lotus was vetoed by lead driver Ayrton Senna, who felt the team could only support one strong driver and pushed for a weak pay-driver as number two. Warwick would likely have struggled against Senna in equal machinery, but he would at least have had an opportunity for race victories. Finally, and most significantly, Warwick rejected a move to Williams in 1985 in favor of Renault, right as Renault began to wind down their F1 effort and Williams hit the front. Williams hired Nigel Mansell instead, and the rest is history.

80. Jean-Pierre Beltoise

(5.52 ppr, 1972-1974)

Jean-Pierre Beltoise was a highly talented driver of the early 1970s, not quite at the level of the era’s best, but consistently rated the 5th or 6th best driver on the grid by the model. Beltoise is best remembered for a single brilliant victory at Monaco in torrential rain, an outlier result that carries less weight with the model’s robust scoring system. Partly for this reason, Beltoise is rated lower than he was in the old f1metrics rating list. Another key contributor to this change is the model recognizing Niki Lauda’s inexperience when he was paired with and beaten by Beltoise.

Beginning with Matra, Beltoise was the team’s sole driver for most of 1968. He impressed with 2nd in the wet Dutch GP in only his eight start. In 1969, he was joined at Matra by Jackie Stewart, and was dominated by his outstanding teammate 1-7 in counting races, 1-10 in qualifying, and 21-63 in points. In his third season, Beltoise faced Chris Amon and was beaten 2-3 in counting races, 1-6 in qualifying, and 1-6 in points.

In all other seasons, Beltoise outperformed his teammates, including Clay Regazzoni and an inexperienced Niki Lauda. Beltoise raced in Matra’s sportcar program in parallel with F1, where an unfortunate accident in 1971 resulted in the death of Ignazio Giunti, caused by Beltoise pushing his car along the circuit after running out of fuel. Beltoise’s international racing license was suspended for three months, resulting in him missing three grands prix. Retiring from F1 in 1974, Beltoise moved into touring car racing and rallycross.

79. Pastor Maldonado

(5.54 ppr, 2013-2015)

Although a race winner, Pastor Maldonado never shook off his reputation as an incredibly reckless driver whose performances ran hot-cold in every season of his career. Maldonado’s rookie season against Rubens Barrichello looked relatively promising compared to his junior single-seater career, scoring 5-9 in counting races, 9-10 in qualifying, and 1-4 in points. These were similar results to those produced by the more highly touted rookie Nico Hülkenberg, who had raced alongside Rubens Barrichello in the same seat the previous season.

Relatively close battles followed against Bruno Senna (8-8 in counting races, 17-2 in qualifying, and 43-30 in points) and against the rookie Valtteri Bottas (10-7 in counting races, 7-12 in qualifying, and 1-4 in points). Against Romain Grosjean, Maldonado’s performance level was finally more clearly benchmarked against an experienced driver. Maldonado was consistently outpaced over two seasons, scoring 8-12 in counting races, 5-28 in qualifying, and 29-59 in points. Having been sponsored by the Venezuelan government, Maldonado’s career ended when the country’s economy collapsed.

78. Gilles Villeneuve

(5.55 ppr, 1979-1981)

As I noted last time I wrote an all-time ranking list, if we take anecdotes over achievements, Villeneuve is surely one of the greatest of all time. With an unsentimental mathematical model that only considers race results (and doesn’t consider team orders in 1979), Villeneuve remains ranked outside the top 50.

Villeneuve was a spectacular driver with uncanny car control and wet-weather flair, but he also made frequent driver errors. In 1978, he was beaten by the more experienced Carlos Reutemann 6-7 in counting races, 4-12 in qualifying, and 17-48 in points. Against Jody Scheckter, Villeneuve scored 11-5 in counting races, 20-9 in qualifying, and 59-62 in points. In this instance, the total points tally does not tell the full story. Villeneuve was often the quicker driver in 1979, when Ferrari had the dominant car, but Scheckter emerged as the number one driver, in part due to poorer reliability for Villeneuve. In 1980, when Villeneuve was clearly beating Scheckter, the car was scarcely capable of points.

From 1981 to his fatal accident in 1982, Villeneuve raced alongside Didier Pironi at Ferrari. Pironi is not rated particularly highly by the model (128th of all-time), having been outperformed by every teammate he faced in F1 (Tambay, Jarier, Laffite, Villeneuve). Overall, against Pironi, Villeneuve scored 3-4 in counting races, 14-6 in qualifying, and 31-19 in points, which the model only considers a moderately strong result against a driver with Pironi’s record.

Villeneuve’s tragically short career is the topic of one of my recent historical hypothetical posts. The conclusion of that post is that, had he lived, Villeneuve would most likely have won the 1982 and 1983 drivers’ titles for Ferrari.

77. Paul di Resta

(5.55 ppr, 2011-2013)

The F3 Euro champion in 2006, ahead of teammate Sebastian Vettel, Paul di Resta never fully converted his early potential into results in F1. di Resta spent three seasons in F1, racing alongside Adrian Sutil in his first and third seasons. Sutil was already in his fifth season when di Resta was a rookie, and he outperformed di Resta that season. di Resta turned the tables when they met again, resulting in di Resta narrowly leading their overall head-to-head record 17-15 in counting races, 19-17 in qualifying, and 75-71 in points. Given the experience differential, the model interprets this match-up as evidence that di Resta was superior to Sutil.

In his second season, di Resta faced Nico Hülkenberg, also in his second season after returning from a year spent testing. Although di Resta started the season very strong, leading Hülkenberg 6-1 in counting races and 5-2 in qualifying, Hülkenberg dominated the second half of the season to ultimately beat di Resta 8-11 in counting races, 8-11 in qualifying, and 46-63 in counting races.

76. Jacky Ickx

(5.55 ppr, 1970-1972)

Jacky Ickx simultaneously competed for the top prizes in both F1 and sportcars, winning Le Mans 6 times and twice finishing 2nd in the World Drivers’ Championship.

The model estimates that 1968, Ickx’s first full F1 season, was his strongest career performance. An experienced endurance racer and F2 campaigner, Ickx had made his talent clear to the F1 paddock when he ran as high as 5th place in an F2 car during a combined F1/F2 race at the Nürburgring in 1967, overtaking twelve F1 cars. In 1968, Ickx raced in F1 alongside the more experienced Chris Amon, scoring 4-1 in counting races, 2-7 in qualifying, and 27-10 in points, finishing an impressive 4th in the championship.

Ickx solidified his reputation by beating Jack Brabham 3-0 in counting races, 4-4 in qualifying, and 18-14 in points. However, Brabham was by this stage 43 years old, which the model now takes into consideration. Ickx spent 1970-1973 racing for Ferrari with Mario Andretti, Clay Regazzoni, and Arturo Merzario (ranked 137th). Versus Andretti, Ickx scored 2-3 in counting races, 8-3 in qualifying, and 31-16 in points. Versus the less experienced Regazzoni, Ickx was ahead 14-3 in counting races, 16-13 in qualifying, and 86-61 in points. Versus Merzario, Ickx was ahead 4-2 in counting races, 5-4 in qualifying, and 17-7 in points.

In 1974, Ickx was comprehensively beaten by a teammate for the first time in his career. Against the highly talented Ronnie Peterson, he scored 3-7 in counting races, 3-21 in qualifying, and 15-38 in points. In the following years, Ickx made only sporadic appearances for Williams, Ensign, and Ligier before bowing out of F1.

75. Olivier Panis

(5.59 ppr, 1996-1998)

Olivier Panis was a rising star in F1, having won the 1996 Monaco GP, when he suffered a massive accident at the 1997 Canadian GP. With both legs broken, he missed the remainder of the season. On return, Panis’ results were seemingly never at the same level, though he remained a highly respected test driver. On the other hand, Panis’ teammates — including Jarno Trulli and Jacques Villeneuve — were generally stronger post-1997. So was it the injury that hampered Panis’ performances, or did better teammates simply create the illusion that Panis’ form had faded? Without a model that could track a driver’s trajectory across age and experience, these possibilities were previously difficult to disentangle.

Now, armed with a model that can account for the trajectory of performance across a driver’s career, we can reexamine the question. In the graph above, Panis’ performances were steadily rising from his rookie year up to 1997. In 1997, he is rated the 5th best performing driver on the grid. In the remainder of his career, after return from the injury, he is never again rated within the top 10. On this basis, it seems likely that the injury was indeed a career turning point, which impacted Panis’ subsequent performances.

74. Mike Hawthorn

(5.71 ppr, 1952-1954)

Mike Hawthorn was Britain’s first champion, taking the 1958 championship from Stirling Moss, after the latter sportingly pleaded Hawthorn’s case in a key race to avoid Hawthorn’s disqualification. The model sees Hawthorn as one of the stronger drivers of the 1950s, but the weakest champion of that decade, behind Giuseppe Farina, Alberto Ascari, and Juan Manuel Fangio.

Three of Hawthorn’s teammates appeared clearly quicker in equal equipment. Against Giuseppe Farina, he was beaten 2-6 in counting races and 1-10 in qualifying. Against Alberto Ascari, he was beaten 3-5 in counting races and 0-9 in qualifying. Against José Froilán González (no ranking), he was beaten 1-2 in counting races and 1-6 in qualifying.

Two of Hawthorn’s teammates had mixed records against him. Against Luigi Villoresi (no ranking), Hawthorn scored 3-3 in counting races and 2-8 in qualifying. Against Peter Collins, Hawthorn scored 3-2 in counting races and 8-3 in qualifying.

Against his other teammates, Hawthorn was generally significantly quicker. He beat Maurice Trintignant 4-3 in counting races and 12-1 in qualifying, Luigi Musso (ranked 117th) 5-3 in counting races and 7-2 in qualifying, and Wolfgang von Trips (no ranking) 3-1 in counting races and 5-0 in qualifying.

Mike Hawthorn retired at the end of 1958, reigning champion and aged 29, but suffering a terminal kidney disease. He died in a motor vehicle accident months later.

73. Jack Brabham

(5.76 ppr, 1959-1961)

Jack Brabham was not the ultimate quickest driver of his generation, his performances wavering greatly between seasons, but the mark he left on the sport is among the most significant and indelible of any driver.

The team that Brabham developed became one of the F1 powerhouses, winning 35 races (including eight 1-2s), two constructors’ titles, and four drivers’ titles. Most remarkably, Brabham won a championship in a car of his own construction in 1966, aged 40. This is a feat unlikely to ever be replicated in F1.

Brabham’s season performances are curiously depressed across the period 1961-1965. This corresponds to the period in which F1 used a smaller engine formula, resulting in less powerful cars, perhaps not suiting Brabham’s style. However, it also a period in which Brabham was keenly focused on the development of his own team.

In direct head-to-heads, Brabham was beaten by several other greats of his era, including Jim Clark, Dan Gurney, Jochen Rindt, and Jacky Ickx. But at his absolute best, in the period 1959-1960 (when racing was his sole focus), the only driver on the grid who was clearly quicker was Stirling Moss.

72. Ralf Schumacher

(5.80 ppr, 2004-2006)

Ralf Schumacher had an impossible benchmark in his brother, but he could be unbeatably quick on his day. Previously ranked inside the top 50, Ralf’s rating has fallen due to new drivers joining the list, as well as him now receiving less credit for results against inexperienced teammates Jenson Button and Juan Pablo Montoya, and his thrashing of Alex Zanardi (no ranking) who was then on a comeback after four years out of the sport.

In his rookie year, Schumacher was slightly outperformed by Giancarlo Fisichella (in his second season), scoring 4-6 in counting races, 7-10 in qualifying, and 13-20 in points. In 1998, Schumacher partnered ex-champion Damon Hill, scoring 3-4 in counting races, 10-6 in qualifying, and 14-20 in points. This would have been a positive record had Schumacher been allowed to pass Hill for the lead at Spa.

Moving to Williams in 1999, Schumacher dominated Alex Zanardi 5-2 in counting races, 11-5 in qualifying, and 35-0 in points, putting a rapid end to Zanardi’s comeback. In 2000, Schumacher was paired with the precocious rookie Jenson Button, whom he beat 6-3 in counting races, 11-6 in qualifying, and 24-12 in points. Across 2001-2004, Schumacher was paired with new recruit Juan Pablo Montoya. Although Schumacher was more experienced, the pair were closely matched, with an overall tally of 17-20 in counting races, 28-22 in qualifying, and 173-194 in points.

In 2005, Schumacher moved to Toyota, where he spent three years racing alongside Jarno Trulli. The pair proved to be a close match, with Schumacher scoring 16-22 in counting races, 17-36 in qualifying, and 70-66 in points.

71. Carlos Pace

(5.82 ppr, 1975-1977)

Carlos Pace is often forgotten today, overshadowed by the successes of his Brazilian compatriots Emerson Fittipaldi, Nelson Piquet, and Ayrton Senna. However, he was highly rated by his contemporaries, and ranked #51 of all time by a poll of experts in F1 Racing magazine in 1997.

In his first two seasons, 1972-1973, Pace dominated teammates Henri Pescarolo (ranked 142nd) and Mike Hailwood (ranked 125th). He started 1974 with the Surtees team, outperforming Jochen Mass (ranked 107th), before moving to Brabham. He raced there alongside Carlos Reutemann from 1974-1976, scoring 6-10 in counting races, 17-15 in qualifying, and 39-63 in points. In 1975, he took his only career win at Interlagos — the track now named in his honor.

1977 got off to a promising start with 2nd place at the first round. Unfortunately, Pace was killed after the third round in a light aircraft accident.

70. Jody Scheckter

(5.85 ppr, 1974-1976)

On a good day, Scheckter was one of the best drivers of the 1970s. On a bad day, he was nowhere. Although he won the 1979 title, the model attributes this to a dominant car, ranking Scheckter only the year’s 12th best performer and his teammate Gilles Villeneuve the year’s 9th best performer. In the model’s estimation, Scheckter’s peak period came earlier than this.

Scheckter’s career began in ignominious fashion, as he DNFed from every start in 1973. On debut, he was running 3rd until he spun. He looked set for victory in his third race, but crashed into Emerson Fittipaldi, prompting the Brazilian to call Scheckter a “menace to himself and everybody else”. At the next race, Scheckter caused a massive pile-up, leading to the McLaren team resting him for four rounds. On return, he crashed again.

Witnessing the harrowing fatal crash of François Cevert at the end of 1973 led to a fundamental refinement of Scheckter’s driving, as he became a far more careful and precise competitor.

“From then on, all I was trying to do in Formula One was save my life.” – Jody Scheckter

The model ranks 1974 as Scheckter’s finest season. This was a year in which he dominated teammate Patrick Depailler 45-12 in points to finish 3rd in the championship. Racing alongside Depailler from 1974-1976, Scheckter led 19-10 in counting races, 27-18 in qualifying, and 114-65 in points.

Scheckter was a sole entrant for Wolf across most of 1977-1978, during which time he finished 2nd in the championship. Without teammates, this period is not informative to the model about Scheckter’s season or overall performance level.

In 1979, Scheckter made a canny move to Ferrari to partner Gilles Villeneuve, replacing Carlos Reutemann, who left the team at the worst possible time. After winning the title in 1979, the 1980 season was an unmitigated disaster, as Ferrari dropped in the blink of an eye from world-beaters to bottom of midfield. Scheckter’s driving that year seemed completely uninspired and he retired at the end of the year.

69. Gerhard Berger

(5.86 ppr, 1992-1994)

Gerhard Berger made his mark racing the massively powerful BMW-engined Arrows and Benetton across 1985-1986. In his first full season, Berger was beaten by the slightly more experienced Thierry Boutsen 3-6 in counting races, 4-12 in qualifying, and 3-11 in points. In 1986, his record against the more experienced Teo Fabi (no ranking) was more promising: 2-3 in counting races, 14-2 in qualifying, and 17-2 in points.

For 1987, Berger had offers from Ferrari and McLaren, choosing Ferrari. Across 1987-1988, he beat the team’s lead driver Michele Alboreto 10-3 in counting races, 28-4 in qualifying, and 77-41 in points. In 1989, Berger faced his first high-level test when Nigel Mansell joined Ferrari. It was a difficult season for Berger, marred by 50% mechanical DNFs and a horrific, fiery accident at Imola. His overall record against Mansell was 1-2 in counting races, 7-7 in qualifying, and 15-38 in points.

When Alain Prost left McLaren in 1990, Berger gladly accepted the seat alongside Ayrton Senna. Across 1990-1992, Berger served as a reliable but clearly outpaced number two to Senna, scoring 7-19 in counting races, 8-40 in qualifying, and 135-224 in points.

Berger spent the remainder of his F1 career racing alongside Jean Alesi, first at Ferrari then at Benetton. Although Berger was now aged a little past his peak, their head-to-head record was extremely close: 22-19 in counting races, 35-42 in qualifying, and 126-151 in points. While 1993 was a troubled season for Berger, marred by strange accidents, he bounced back in 1994 while dealing with the trauma of his friend Senna’s death at Imola. The model rates Berger’s 1994 season as his career-best performance. Berger had 8 mechanical DNFs in 16 starts that season, finishing 6 times on the podium, with 1 race win, ending a nearly four-year drought for Ferrari.

68. Damon Hill

(5.87 ppr, 1994-1996)

During his F1 career, Damon Hill’s success was a subject of almost constant critique. Landing in the dominant Williams-Renault in his first full season, Hill had a championship contending car for four consecutive seasons, including a dominant car with a rookie teammate in 1996. It was argued that he won his title almost by default. The previous incarnation of the f1metrics model was relatively sympathetic to Hill, ranking him #35, ahead of twelve other champions, including his father, Graham Hill. The updated model has dropped Damon’s ranking behind that of his father, and now ahead of only six other champions (Jody Scheckter, Jack Brabham, Mike Hawthorn, Denny Hulme, John Surtees, and Phil Hill who is outside the top 100 at 139th).

What are the factors that have led to a downward adjustment of Damon Hill’s performance? First, we can consider his 1993 season against Alain Prost. The model recognizes that Prost, at age 38 and coming back from a one-year sabbatical, was likely past his best. However, it also recognizes that Hill was inexperienced, making this a close to fair comparison. In the years that followed, however, Hill was at a consistent advantage to his Williams teammates. David Coulthard was a rookie, who debuted in difficult circumstances following Ayrton Senna’s death in 1994. The model now takes Coulthard’s inexperience into account when it indirectly compares Hill’s strong record against Coulthard (10-4 in counting races, 17-8 in qualifying, and 131-63 in points) to Mika Häkkinen’s record against a much more experienced Coulthard (35-26 in counting races, 68-31 in qualifying, and 360-296 in points). Similarly, the model now considers Hill’s significant experience advantage in 1996 against his rookie teammate Jacques Villeneuve.

Hill demonstrated that he had genuine talent on several occasions, including his stand-out performances for Arrows in 1997 and his brilliant drive at Suzuka 1994. But without the aid of a dominant car, the model does not see Hill challenging for titles in the 1990s.

67. Chris Amon

(5.90 ppr, 1970-1972)

Though Chris Amon had 96 starts, 40% of those were mechanical DNFs, leaving him with 58 counting races. Famously unlucky, Amon never won an F1 race despite 19 front-row starts, 5 poles, and 183 laps led. He is commonly listed among the best drivers to never win a race. Amon’s rating by the f1metrics model has slid from #26 in the old list to #67, taking him out of contention for the model’s best ranked driver to never win a race. This change can be explained by a few factors, the most important being that the model now takes works vs. customer car status into account in teammate comparisons that were previously highly favorable to Amon.

Amon entered F1 in 1963, racing for Reg Parnell. He competed sporadically across 1963-1966 in customer cars, finishing just five races in this period. After winning the 1966 Le Mans race for Ford, Amon was invited to meet with Enzo Ferrari, leading to his signing at Ferrari for 1967. In 1967, Amon dragged Ferrari’s uncompetitive challenger into 5th in the championship and is ranked by the model the year’s 3rd strongest performer. In 1968, he showed great qualifying pace, taking 3 pole positions, but was outscored 27-10 by teammate Jacky Ickx after uncharacteristically crashing at both the Nürburgring and Monza. Reliability problems disrupted Amon’s 1969 campaign, with 5 failures in 6 starts (meaning he has no estimated performance level for the season in the above graph); he nonetheless achieved Ferrari’s best race finish of 3rd that year.

In 1970, Amon drove for the works March outfit, outscoring teammate Jo Siffert (ranked 119th) 23-0 and the customer entries of Ronnie Peterson (20-0) and François Cevert (17-1), but he was outscored by the customer entries of Mario Andretti (2-4) and Jackie Stewart (14-25). Now that the model considers the relative competitiveness of works vs. customer entries, Amon’s 1970 performance is adjusted downwards, although still ranked 3rd best of the year.

In 1971, Amon moved to the works Matra team, where he beat Jean-Pierre Beltoise 3-2 in counting races, 6-1 in qualifying, and 6-1 in points. Amon’s appearances subsequently dwindled until retirement in 1976, mostly appearing as a sole entrant for Matra, Tecno, Ensign, and the shortly-lived Amon team.

66. Patrick Depailler

(5.92 ppr, 1977-1979)

At his peak, in 1977, the model ranks Patrick Depailler as the 5th best performing driver on the grid. Ranked inside the all-time top 50 by the old f1metrics model, he is rated slightly lower in the updated list, due to the model now considering that Didier Pironi was a rookie when he faced Depailler, as well as the addition of new drivers to the list.

Depailler spent nearly his entire career at Tyrrell. From 1974-1976, he raced alongside Jody Scheckter, with both drivers having previously only started a handful of F1 races. Overall, Depailler was outperformed by Scheckter, scoring 10-19 in counting races, 16-27 in qualifying, and 65-114 in points. Depailler’s results were more impressive against the highly rated Ronnie Peterson, scoring 2-3 in counting races, 9-8 in qualifying, and 20-7 in points.

In 1978, Depailler was paired with the rookie Didier Pironi (ranked 128th), whom he soundly beat 6-2 in counting races, 14-2 in qualifying, and 34-7 in points. In 1979, Depailler raced only the first 7 rounds for Ligier before breaking both legs in a hang-gliding accident. In that half-season, he was beaten by Jacques Laffite 0-3 in counting races, 3-4 in qualifying, and 22-24 in points. Shortly after his comeback with Alfa Romeo in 1980, Depailler died in a testing crash.

65. Kamui Kobayashi

(5.92 ppr, 2010-2012)

Kamui Kobayashi is remembered as an aggressive and opportunistic overtaker. He debuted for Toyota in the final two rounds of 2009, where he immediately impressed against teammate Jarno Trulli. In 2010, he continued his form, beating two veteran teammates. He beat the 39 year old Pedro de la Rosa (ranked 105th) 7-2 in counting races, 8-7 in qualifying, and 27-6 in points, including one additional race together in 2011; and Nick Heidfeld 3-1 in counting races, 4-1 in qualifying, and 11-6 in points.

In 2011, Kobayashi was joined at Sauber by the rookie Sergio Pérez. In their first season as teammates, Kobayashi was able to hold his own, scoring 7-5 in counting races, 7-11 in qualifying, and 14-14 in points. In the following season, Pérez appeared to have clearly greater pace, but was inconsistent between weekends, resulting in a closely balanced 9-8 in counting races, 9-10 in qualifying, and 60-66 in points.

After failing to find a seat in F1 for 2013, Kobayashi returned with Caterham team in 2014 alongside the rookie Marcus Ericsson. The head-to-head result was 5-3 in counting races, 7-3 in qualifying, and 0-0 in points. With Caterham folding at the end of the season, Kobayashi left F1 for good.

64. Mark Webber

(5.95 ppr, 2008-2010)

Mark Webber came within a hair’s breadth of winning a title for Red Bull in 2010. In subsequent years, he looked a distant number two to Sebastian Vettel. Was Vettel underperfoming in 2010 or was Webber briefly among the best drivers of the era? By the model’s estimation, the former is a far more probable explanation. While he was a solid performer, the model never sees Webber as a top 10 driver in the era he raced.

Always a qualifying ace, Webber made a name for himself with memorable low-fuel glory runs for Jaguar. Across his first four years in F1, Webber dominated a series of lowly rated teammates. He faced his first real challenge in 2005, when paired with Nick Heidfeld at Williams. Across their races together (before Heidfeld’s injuries), Webber scored 4-6 in counting races, 9-5 in qualifying, and 24-28 in points. The points total fell in Heidfeld’s favor despite Heidfeld losing more potential points to mechanical DNFs.

In 2006, Webber was paired with the rookie Nico Rosberg, whom he led 5-3 in counting races, 12-6 in qualifying, and 7-4 in points. Accounting for Webber’s age and experience advantage, the model considers this a result slightly in Rosberg’s favor (i.e., Rosberg would be expected to outperform Webber if at equivalent age and experience). Moving to Red Bull, Webber paired with David Coulthard for the final two seasons of Coulthard’s career. Webber held a clear edge, scoring 19-4 in counting races, 31-4 in qualifying, and 31-22 in points.

The final phase of Webber’s career began in 2009, when he was paired with the 21 year old Sebastian Vettel. Immediately, Webber appeared to have a major challenge on his hands, as Vettel brought the 2009 Red Bull into championship contention. In 2010, Webber was potentially on track for the title until his unforced error in Korea. Teammate Vettel had a quite imperfect season as well, narrowly taking the title at the final round in what the f1metrics model considers a dominant car that should have easily taken both titles, taking drivers out of the equation.

Beyond 2010, as Vettel came into his prime, Webber was largely a non-entity, despite driving championship-winning cars. While Vettel completely dominated the 2011 and 2013 seasons with 24 race victories, Webber finished 3rd in each championship, collecting just a single, lucky race victory when Vettel encountered gearbox issues at the 2011 Brazilian GP. Hampered by major off-season injuries and consistently poor starts in cars that were engineered to lead races not cut through traffic, Webber achieved close to what the model considers the bare minimum those Red Bulls were capable of achieving in the hands of any other driver on the grid.

63. Heikki Kovalainen

(6.03 ppr 2010-2012)

Given the appreciation these days for Lewis Hamilton as one of the all-time greats, Heikki Kovalainen’s performances perhaps deserve a reappraisal. Kovalainen was pilloried for his inability to get anywhere close to Hamilton at McLaren from 2008-2009. Yet, the model suggests many other drivers of the era, including Mark Webber, would have suffered a similar fate.

Kovalainen had a very promising rookie season, defeating the more experienced Giancarlo Fisichella 10-4 in counting races, 9-8 in qualifying, and 30-21 in points. In his second season, he was drafted to McLaren as a replacement for the suddenly outgoing Fernando Alonso, joining Lewis Hamilton in his own second season. Kovalainen’s failure to meaningfully challenge Hamilton effectively ended interest in him from top teams, as he was replaced for 2010 by Jenson Button.

Versus Hamilton, Kovalainen trailed by a median 0.13% of lap-time, better than the 0.28% of Jenson Button and the 0.19% of Valtteri Bottas, but worse than the 0.07% of Nico Rosberg and 0.05% of Fernando Alonso. But it should be noted that this comparison is made difficult by Kovalainen racing in the refueling era, with race fuel loads in qualifying. In counting races, Kovalainen scored 10-18 against Hamilton (ahead 36% of races), better than Bottas’ tally of 15-39 (28%), but worse than Button (43%), Rosberg (44%), and Alonso (59%). In summary, Kovalainen ranks behind all of Hamilton’s teammates except perhaps Bottas in a direct head-to-head comparison. Given the quality of that group, which contains three world champions, this is no major slight on Kovalainen.

62. Bruce McLaren

(6.04 ppr, 1963-1965)

Bruce McLaren was one of the finest drivers of the 1960s. Debuting in 1958, McLaren spent his first two full seasons (1959-1960) at Cooper alongside Jack Brabham, winning his first race in 1959 at age 22. Brabham won the drivers’ title on both occasions, though the younger, less experienced McLaren pushed Brabham hard for the 1960 title. McLaren’s overall record against Brabham across 1958-1961 was 5-10 in counting races, 3-22 in qualifying, and 64.5-75 in points.

McLaren continued to race for Cooper until 1965, while establishing his own racing team. Over this time period, the model rates McLaren among the top 3 performing drivers on the grid. However, Ferrari and Team Lotus were now the dominant forces. McLaren was no longer in the right place to challenge for titles. The team he founded continued to gain pace, ultimately becoming one of the most successful teams in F1 history, but Bruce was sadly killed in a testing crash in 1970, aged 32.

61. Eddie Cheever

(6.05 ppr, 1981-1983)

Note: Only 8 American drivers have completed the necessary seasons to have a 3-year peak. See the Honorable Mentions section for another highly rated American driver.

Previously the highest-rated American driver, Eddie Cheever is third under the new model rankings, slightly behind Mario Andretti and Dan Gurney. Cheever never won an F1 race, but in his defense he only spent one season in a car worthy of wins. His career mechanical DNF rate was 54%, the second highest of any driver in the top 100.

Although born in the US, Cheever grew up in Rome and took a traditional pathway through European single-seaters to reach F1. After a spell in the extremely unreliable and slow Osella and Theodore cars, he secured a full-time drive at Tyrrell for 1981, spending most of the season alongside the rookie Michele Alboreto. Cheever finished ahead 3-0 in counting races, 8-4 in qualifying, and 8-0 in points.